The Adam Ellis/Keratin Plagiarism Scandal

To the victim of plagiarism, the injury is often deeply personal. It can be very hurtful to release a personal work, something that takes a great deal of courage to do, and then see other people coopting it under their name.

That pain gets even worse when the plagiarized work goes on to be successful, either by winning awards or wins awards, finding commercial success or simply becoming popular.

For cartoonist Adam Ellis, a recent plagiarism of his work was the worst of all of those worlds.

Yesterday, Ellis took to Twitter to express his frustration at the short film Keratin, which was making rounds on the independent film circuit and winning several awards.

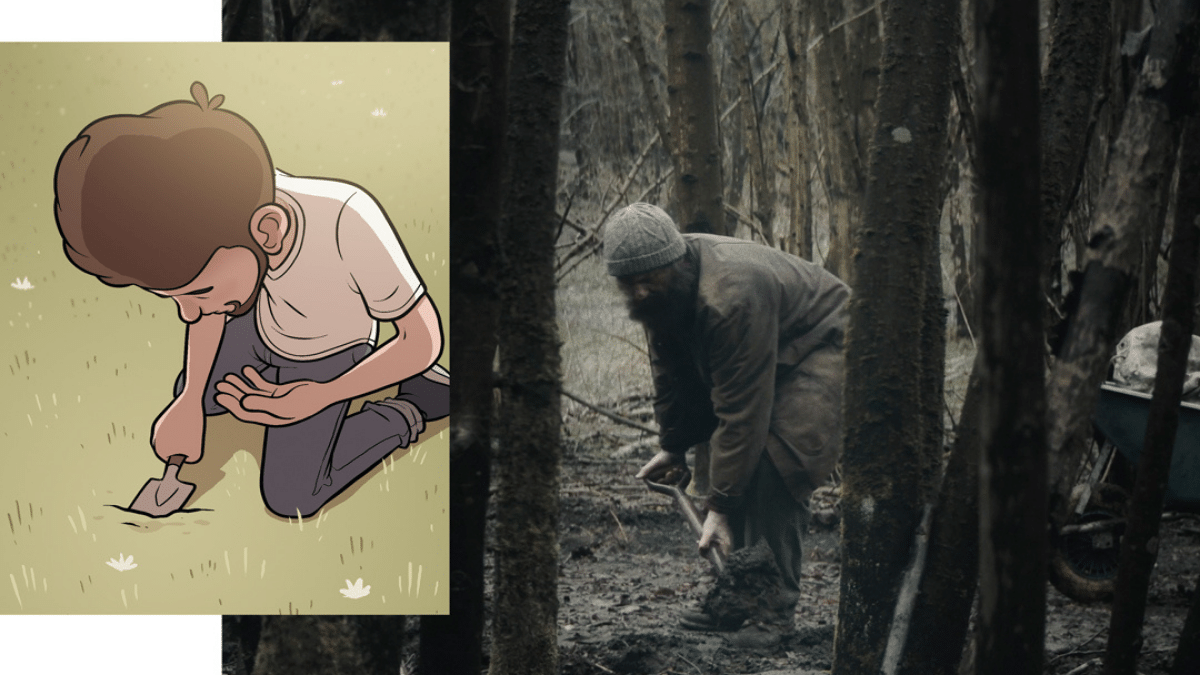

The claims were straightforward and bold. According to Ellis, the 7-minute film was a shot-for-shot plagiarism of a comic he created back in back in January 2018.

The comic featured a protagonist burying a fingernail clipping in the earth and, after some time had passed, finding it had grown into a whole new person that he took in and began to care for.

According to Ellis, this comic was deeply personal to him and his leaving Buzzfeed around that time.

To make matters worse, Ellis further claimed that the directors of Keratin, Andrew Butler and James Wilson, reached out to him in October (via a producer) asking for him to help promote the movie.

In their email, the producer acknowledged that the film “takes some influence from your work” and claims that, “We have credited you in our short film as an influence.”

However, that credit didn’t appear anywhere in the film or its marketing material.

According to Ellis, when he expressed his disapproval for the project, they responded by blocking him on social media. However, Ellis took no action until the film debuted on the site Directors Notes, which also published an interview with the directors.

There, they admitted that “The original concept was inspired by a short online cartoon we saw, which we developed further,” but did not name Ellis or the original comic directly.

Now, Directors Notes has pulled the film as well as the interview, saying that they were unaware of the plagiarism.

Furthermore, the IMDB rating for the film sits at exactly one star, as the public backlash to the film has only grown. Likewise, several festivals have contacted Ellis to say that they have removed the film and the main actor in the work has said he was unaware of the plagiarism and never would have done the part if he had known.

Ellis, for his part, says he is not interested in taking legal action at this time but is keeping his options open. The directors have not responded at all, remaining silent despite multiple media outlets trying to reach them for comment.

It seems to be a swift and decisive end to this case, but one that leaves a lot of question open. One of the most important being, “Why does this story feel so familiar?”

Echoes of 2013 and Shia LaBeouf

If Ellis’ story sounds familiar, it’s because it’s remarkably similar to what happened in December 2013 between actor Shia LaBeouf and comic artist Dan Clowes.

In that story, LaBeouf released a film entitled HowardCantour.com. However, after its release, users noticed that it was virtually identically to a 2007 comic by Clowes entitled Justin M. Damiano. This included both shots and images from the comic as well as dialogue.

In the bizarre series of events that followed, LaBeouf initially apologized for the plagiarism, though that apology was later discovered to be plagiarized in its own right.

However, things then took an even more bizarre turn as he hired a skywriter to write a message over the skies of Los Angeles. He then responded to a cease & desist letter sent by Clowes’ publisher with a series of mocking tweets and even threatening to create another film based on Clowes’ work.

By the time it was all over, the media uncovered more than a dozen instance of LaBeouf copying the works during this time period.

That said, the story largely fizzled out. No lawsuit emerged and LaBeouf carried on with his career, with all of its bizarre turns, almost completely unscathed.

However, this is where Ellis’ story likely takes a different turn, Butler and Wilson are not Shia LaBeouf. LaBeouf was nearly at the peak of his celebrity at the time. Butler and Wilson are two largely unknown directors that are now best known for plagiarism.

Despite this, many people have been encouraging Ellis to take legal action. This is something Ellis himself has expressed reservations about doing. But what if he did? The outcome is actually uncertain.

The Problem with Litigation

To be clear, I don’t think that there is much doubt that Keratin is an infringement of Ellis’ comic.

Though some have expressed doubt of infringement, since much of what is copied is concepts and ideas, the fact actual shots and images are used and the creators acknowledged that influence, makes it at least likely he could show it to be an unlawful derivative work.

But that could wind up being a very pyrrhic victory. In the United States, before any lawsuit can be filed, a rightsholder must first register their work with the U.S. Copyright Office.

If Ellis wanted to file a lawsuit and hasn’t registered his work yet, filing that registration would be the first step.

However, if the registration wasn’t filed before the infringement took place, Ellis would be deeply limited on the damages he could claim. He would only be able to sue for actual damages, meaning the greater of their gains or his losses, and neither would be that great. Even worse, Ellis would not be able to seek attorneys’ fees and court costs, meaning the case would almost certainly cost more than he could ever hope to gain.

In short, even though Ellis likely has a good argument that he was infringed, that doesn’t mean a lawsuit is practical or well-advised. He could, like many plaintiffs before him, wind up bankrupting himself to prove a point.

Personally, I consider this one of the key reasons we need to end the registration requirement in the United States. Rightsholders, like Ellis, typically aren’t able to register all of their work and this shuts them out of the legal system.

That said, there is one major change that could address that (at least in some cases). Back in December, the Copyright Alternative in Small Claims Enforcement Act of 2019 (CASE Act) was passed into law as part of the COVID-19 relief bill.

The act establishes a small claims court that rightsholders, like Ellis, might be able to use as a cost-effective tool for addressing these cases. However, that court has not actually opened yet so it’s impossible to know how practical it is in this case.

Bottom Line

However, even if litigation is practical (either small claims or through the regular court system) there’s another question: What’s to gain?

Ellis isn’t likely to see a major financial windfall from this, even if he does win, and punishing the alleged infringer is rarely a good motivator for such actions.

Besides, there’s little punishment that can be achieved in court that hasn’t already been achieved in the court of public opinion. Butler and Wilson now have names synonymous with plagiarism. Before this story, they were known for nothing, now this is what they are known widely for.

To that end, it’s unfortunate for them. If they’d reached out to Ellis before making the film, he would have told them no then but they could have either abandoned the project or taken the idea in a new direction that was wholly theirs.

They handled it about as poorly as possible, not trying to work with Ellis but admitting the influence and even trying to get him to help promote it.

This whole ordeal could have been easily avoided and, if nothing else, it should serve as a warning for other aspiring filmmakers on how NOT to handle your source of inspiration.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.