It’s REALLY Time to End the Registration Requirement

It's actually way past time but now is better than never...

Earlier this week the United States Supreme Court handed down its decision in the case of Fourth Estate Public Benefit Corporation v. Wall-Street.com.

The case looked at whether a rightsholder could file a lawsuit for copyright infringement after the for a copyright registration or if they would have to wait until they actually received or were denied their certificate.

Rightsholders, including organizations like The Author’s Guild, favored the former approach, which had been used in several circuits. However, the court unanimously ruled that a rightsholder must wait for their registration to be completed (or refused), which currently takes an average of 6 months but can take as long as 10 even in the simplest cases.

This means that, if you complete a book and register the day you’re finished. You can not file a lawsuit to get injunctive relief until half a year later. Though you can file an expedited claim, that’s only for certain situations and it costs $800 currently.

You also have the option of preregistering the work, but once again that’s only for certain kinds of works and it costs an additional $140 on top of the regular registration that you’ll have to pursue.

Couple this with the 2014 rule change that made most websites financially infeasible to register, a proposed rise in fees and an antiquated and confusing electronic registration system, the US Copyright Office and the registration requirement are the biggest obstacles to most small creators to enforcing their rights.

The best time to kill the registration requirement was decades ago. The second best time is today.

A Failure in Every Way

In the United States, copyright is attached to a work the moment it becomes fixed in a tangible medium of expression. Every time this post autosaves as I type it, the work I’ve done becomes copyright protected.

However, if you want to do anything with that copyright (other than send takedown notices) you have to register the work with the USCO. This is because only federal courts can hear copyright cases and a registration (now a completed registration) is required before such courts can hear the case.

This means you can’t get injunctions to stop infringements, can’t sue for damages or do anything requiring a court until you receive your registration (or refusal).

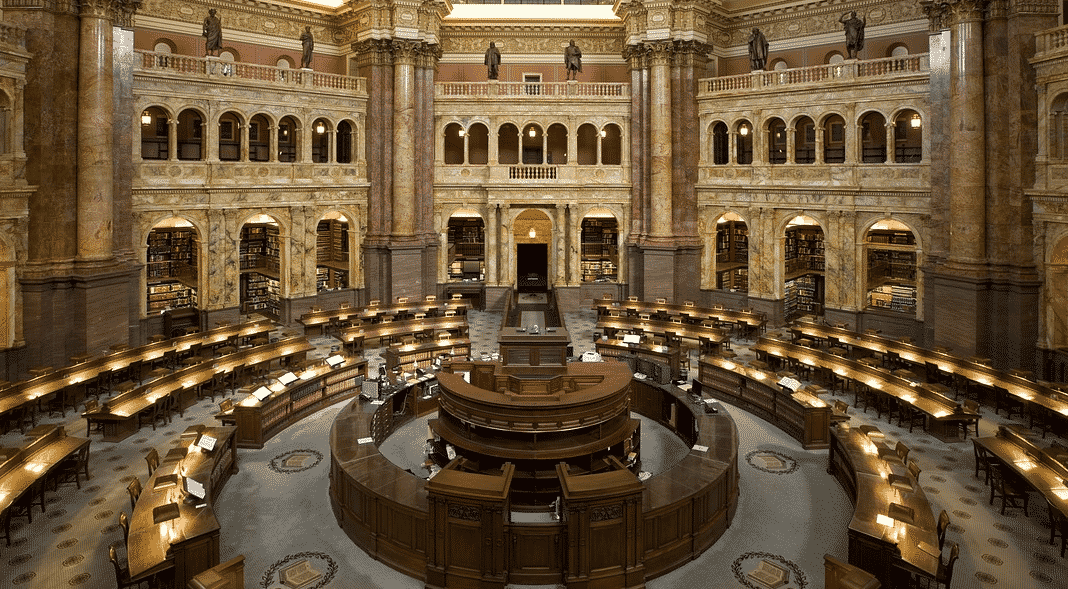

One of the key reasons given for this requiring copyright registrations is the deposit requirement. When submitting a physical work, you’re required to also submit two copies of it. Those copies are then placed in the archives at the Library of Congress, which the USCO is part of.

While this requirement was fairly sensible in a world filled with printed books and physical CDs, most works are digital today. Though the Electronic Copyright Office (ECO) system allows you to “deposit” digital works, the process is basically just uploading it to their servers. You are still required to mail in two copies of primarily physical works.

It’s important to note that the ECO system only came online in 2008. This meant that, if you had a website or other digital-only work before then, the only way to register it was to print out two copies of it and send them along with a paper registration. Something I did for my old poetry website.

However, as infeasible as that was, it’s still far better than the situation today. After a rule change in 2014, required that every post on a website be registered separately. Previously, creators would just register their site once ever three months to ensure timely registration. This rule change forbid that and made it so that every post required a separate registration (and a separate $35 fee).

In short, the stated goal of helping the Library of Congress grow its collection falls apart as the USCO is actively discouraging registrations. By making such registrations more expensive and more difficult, it does nothing to fulfill any of its stated goals.

However, the frustrating part is how the USCO impacts smaller rightsholders, the ones that can least afford it.

Hurting Small Creators, Hurting All Americans

The worst part about the registration requirement is that it harms two types of creators the most:

- Creators that are ignorant of the rules

- Creators that can’t afford to register, whether due to time or money.

While $35 for a simple registration may not seem like much money, it can be a tremendous cost barrier for those putting out a large volume of work, such as daily blog posts. However, that $35 also doesn’t account for the fact that most people need help with their registration (at least the first few times) tacking on at least $100 for that service.

This isn’t a problem for major record labels or big Hollywood studios. The cost of registering (or even preregistering) a work is an incredibly tiny part of their costs when creating and publishing new content.

You can rest assured the latest Drake, Lady Gaga or Ariana Grande album are all going to be properly registered. It’s the upstart or local acts that are unlikely to have all of their ducks in a row.

The registration requirement punishes smaller creators, the ones that are often in the greatest danger of being exploited. It also punishes those who put out a large amount of work, adding a flat fee to every work they want to protect.

But then comes the part that no one wants to talk about: The registration requirement makes it so that, by default, every American’s copyright is worth less than those the copyrights of foreign-created works.

The problem is simple. The Berne Convention, which the U.S. is a signatory, eliminated all registration requirements and formalities. This means that, while American’s have to wait for their registration before they can file a lawsuit, non-Americans do not. Though foreign creators still need timely registration to collect all of their damages and attorneys fees, they can file a lawsuit on day one without bothering with a registration.

To put it bluntly, due to the registration requirement, a newly-created and unregistered American work has less protection than a similar foreign one. It’s that simple.

In short, the registration requirement, and the USCO by proxy, is hurting American creators, giving them second-class protection within their own country. That impact is felt most strongly by smaller creators, the very people that need the USCO’s help the most.

A Not-So-Modest Proposal

The solution to this problem is remarkably simple: Do away with the registration requirement.

Other countries did away with theirs and, along the way, either got rid of or modified the function of their copyright offices. There’s no reason that the United States can’t do the same.

This isn’t the first time I’ve proposed this. I’ve made the exact same suggestion at least a half dozen times including in 2006, twice in 2007, twice in 2009, 2010 and on and on and on.

However, every time I did so I received pushback. Surprisingly, not from groups that want to weaken copyright protection, but groups that describe themselves as pro-copyright and pro-creator.

To them, the registration requirement was a small price to pay for a filled out Library of Congress and the record keeping the USCO provides. While that argument has never been particularly strong or convincing, in wake of the recent Supreme Court ruling, there can be no doubt that the registration requirement hurts all creators and disproportionately harms smaller ones.

There is simply no way to be both pro-creator and pro-registration requirement.

It’s time to abandon this archaic requirement and join the rest of the world.

Bottom Line

The simple truth is this: The registration requirement no longer serves the purpose it was supposed to and instead now only punishes creators that either don’t know they need to register or can’t afford to register all of their work timely.

These problems have been compounded by a USCO that, at almost every turn, has made the process more expensive and more difficult, shutting out even more creators.

Even Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bater Ginsburg, who wrote the opinion, lamented that registration times have increased dramatically but said, correctly, that these are administrative problems the court can’t address.

As disappointing as the Supreme Court decision is, it’s also the correct decision. This requires a legislative solution and the best one is to get rid of the registration requirement, ideally altogether but, at the very least, as a prerequisite for filing a lawsuit.

That simple change would do more to help smaller content creators than just about any other change in the law, with the possible exception of a copyright small claims court.

Though I’ve been calling for this for more than a decade, the Supreme Court just put an exclamation point on why the time has come.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.