Why All Journalists Should Watch Shattered Glass

What a glasshole...

The story of Stephen Glass is one that I am not very familiar with.

The story of Stephen Glass is one that I am not very familiar with.

Unfolding in 1998, at a time when I was a journalism student just graduating high school, I was aware of the scandal and it was raised in my classes. However, it was not something I really delved into. Even my law and ethics classes only briefly touched upon it.

Stephen Glass happened well before I got involved in plagiarism and Glass was a fabulist, not a plagiarist. Though some allegations of plagiarism were alluded to, his crimes were of fiction, not copying.

However, writing ethics do not exist in a bubble. When authors put outcomes ahead of integrity, they commit a wide range of sins. Glass was no different.

So in a bid to catch up on the story, I’ve been revisiting the original reporting at the time, reading the follow ups and generally trying to get a firm grip on the details of Glass’ downfall.

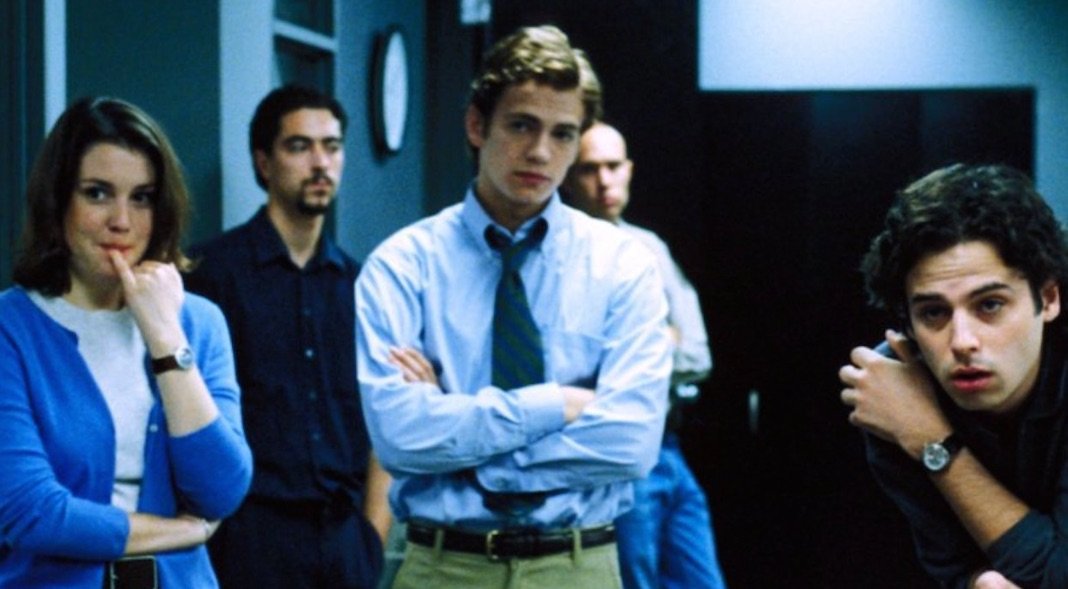

As part of that, I sat down to watch the 2003 film Shattered Glass, a dramatized retelling of Glass’ tenure at The New Republic and the scandal that came with it.

What followed is a flawed but still compelling and accurate retelling of the story. It’s a film that takes almost no liberties and condenses one of journalism’s biggest scandals into just over 90 minutes.

If you’re interested in journalism ethics, or just ethics in writing, this film is a must-watch and it’s easy to see why when you look at the story it’s telling.

The Story of Stephen Glass

The story of Stephen Glass should be familiar to most in journalism but it bears repeating. Note: Technically this plot description will spoil the film but, seeing as how it closely follows the well-known true story, it shouldn’t be much of a spoiler at all.

The story of Stephen Glass should be familiar to most in journalism but it bears repeating. Note: Technically this plot description will spoil the film but, seeing as how it closely follows the well-known true story, it shouldn’t be much of a spoiler at all.

Glass was hired almost immediately after graduation from the University of Pennsylvania by The New Republic, where he initially served and was quickly promoted to writing features.

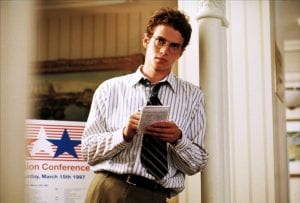

That, in turn, is where the film picks up, with Glass writing for the magazine. Glass, played by Hayden Christensen, is ambitious and eager, but also well liked. He’s a bizarre mix of confident and and self-efacing. He’s quick to apologize for even the smallest slight, eager to help and quick with a compliment.

The first story (in the film) he’s writing is entitled “Spring Breakdown” and focused on drinking, drugs and debauchery at a Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in Washington DC. The accuracy of the story is quickly called into question by the College Republican National Committee but Glass’ editor, Michael Kelly, defends him and stands behind his writer after verifying that the facts were at least plausible.

Things finally began to unravel in May 1998 when, in their May 18th issue, The New Republic published a piece by glass entitled “Hack Heaven”. It was the story of a teenage hacker who broke into the computer systems of a company named Jukt Micronics and was hired as a consultant.

Things finally began to unravel in May 1998 when, in their May 18th issue, The New Republic published a piece by glass entitled “Hack Heaven”. It was the story of a teenage hacker who broke into the computer systems of a company named Jukt Micronics and was hired as a consultant.

However, Adam Penenberg, a reporter at Forbes magazine, went to look into the story, fearing they had been scooped by The New Republic. But, as he and others at Forbes began to look into the story, it quickly began to fall apart.

There was no evidence Jukt Micronics existed, legislation mentioned in the article also didn’t exist. There was no evidence that the hacker nor his hacking group existed nor the conference where Glass supposedly met the parties involved.

Initially, the reporters think that Glass simply got fooled and Glass goes into overdrive to protect himself. He creates a fake website for Jukt Micronics, fake business cards for his supposed sources and even has his brother pose as an executive of Jukt Micronics for a phone call with fact checkers.

Lane takes Glass to the where the conference supposedly took place only to learn that the conference room was closed on Sundays and the restaurant where much of the conversation supposedly took place over dinner was only open at lunch.

Lane suspends Glass for two years but then learns, through a passing comment from another editor, about Glass’ brother at Stanford University. Seeing how deep the deception went, Lane fired Glass and then begins the work of fact checking all of Glass’ previous work at the magazine, eventually finding that 27 of his 41 features were fabricated in part or in whole.

The film ends with Glass testifying before a hearing but neither confirming nor denying his fabrications.

However, for Glass the story continued. Touched on briefly in the film, Glass went on to get a law degree at Georgetown University. But, while he tried in both New York and California, he was not admitted to the bar on moral grounds.

He currently works as a paralegal helping a law firm better tell the stories of injury victims.

Reviewing the Film

When looking at a film like this there are two immediate questions:

When looking at a film like this there are two immediate questions:

- How accurate is the film?

- is the film any good?

The answer to the first question is pretty straightforward: It seems to be very accurate, at least by Hollywood standards. Not only does it match my own research, but those who worked with Glass and worked with him during that time say the film is accurate, if a bit uncanny valley.

While the film may have taken liberties with how competitive The New Republic was in a bid to ramp up the stakes, the film seems to be factually accurate by all accounts.

As for it being a good film, it is, to the say the least, solid.

The acting in the film is good. Hayden Christensen’s Glass comes across as creepy and slimey from almost the first frame. Though Glass’ real-life counterparts say that wasn’t accurate, they also say it doesn’t stray far from the truth.

It’s as Glass’ slide into the abyss begins that Christensen’s real work begins. Christensen was criticized for being too whiny in the Star Wars prequels, which this film was released at the same time as. As Glass’ world crumbles, his demeanor becomes more like Anakin’s but in this film it feels appropriate.

Where Christensen’s performance as Anakin came across as an “emo teen”, here it really does smell of the desperation Glass must have been feeling. It does well to make Glass seem like a genuinely distressed, but not a sympathetic character.

Where Christensen’s performance as Anakin came across as an “emo teen”, here it really does smell of the desperation Glass must have been feeling. It does well to make Glass seem like a genuinely distressed, but not a sympathetic character.

The other actors also do well, in particular Peter Sarsgaard, who plays Lane. He’s a colder, calculating foil for Glass and the contrast in performances works well.

The largest negative about the film is that, at times, it can be confusing. The film is shot partially out of sequence, with several flashbacks including a recurring one with Glass talking to a class of journalism students at his former high school.

The confusion reaches a peak as Forbes begins to investigate and the team at that magazine is introduced without much of a word. It’s easy to miss, especially in a film already filled with characters that are mostly just background noise to the story.

I would advise anyone watching this to go in with a basic understanding of the scandal and how it unfolded. It makes the film much easier to watch.

Still, even without that it’s a solid retelling and one that should be required viewing for anyone seeking to enter into journalism or a career as a professional writer.

Why it Should Be Required

The reasons I would recommend making this film required viewing is two-fold.

The reasons I would recommend making this film required viewing is two-fold.

First, Glass’ story has been largely forgotten. His story took place in 1998, this film was released in November 2003 to little fanfare. Part of the reason may be that, on May of 2003, the Jayson Blair scandal unfolded.

Glass’ story was eclipsed pretty thoroughly but it’s an important tale to remember, especially in this era of journalism where the veracity of every story is called into question.

But more importantly, the film does an excellent job of explaining how journalism worked (or was supposed to work) in the late 90s.

There’s an excellent 2-3 minute piece where Glass talks to the students about the rigorous fact checking and editing that take place after a piece is submitted. How the piece is passed through multiple editors, fact checkers and lawyers on the way to the magazine’s pages.

However, as he explained how rigorous the process worked and how onerous the system could be, he also explained the flaw in it. That many times the only thing a fact checker has to go on is the reporter’s notes.

While that’s likely how Glass got away with his earlier lies, by the end of his tenure he was also the head of the fact-checking department, making it even easier.

While the rigorous multi-day editing process for a story seems almost quaint in the age of Twitter-based news, it’s an important reminder of the lengths that journalists went to, and still sometimes go to, to make sure a story is accurate and well-written.

That alone makes this movie more than worth the watch.

Bottom Line

The story of Stephen Glass is an important one, especially to journalists. Though it’s been largely overshadowed by Jayson Blair, it’s every bit as important today as it was in 1998.

The story of Stephen Glass is an important one, especially to journalists. Though it’s been largely overshadowed by Jayson Blair, it’s every bit as important today as it was in 1998.

To that end, Shattered Glass is a capable and accurate retelling of the scandal and how it unfolded. Though I’d recommend being aware of the key elements of the story before watching, it’s a film well worth seeing.

Bear in mind though, this isn’t a movie you watch for the plot. There are no surprises and history is the ultimate spoiler. Instead, the audience of this movie is more of an archeologist watching a key event in history unfold. The goal is to put faces to the names, emotions to the events and context to the story.

The goal is to make you, the viewer, personally invested in this story and that is something it does well. That, in turn, makes the story far more impactful than it can be as just words on paper.

To do that, while maintaining an accurate retelling of the story is pretty magical and that makes it a film well worth seeing.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.