The DMCA, Fair Use and Dancing Babies

Earlier this week the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a ruling that has literally been eight years in the making. In a ruling in the Lenz v. Universal case (often referred to as the “Dancing Baby” case), the court ruled that rightsholders must consider fair use before filing a Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) notice to get allegedly infringing material removed.

Earlier this week the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a ruling that has literally been eight years in the making. In a ruling in the Lenz v. Universal case (often referred to as the “Dancing Baby” case), the court ruled that rightsholders must consider fair use before filing a Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) notice to get allegedly infringing material removed.

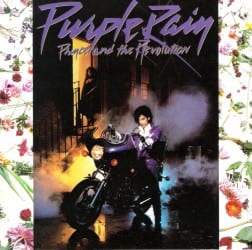

The case revolves around a 29-second video that was uploaded to YouTube in 2007. The video features the then-13-month-old son of Stephanie Lenz dancing to the Prince song Let’s Go Crazy. Universal filed a takedown notice with YouTube ordering its removal, YouTube complied and the video stayed for a short period of time before it was restored by a counter-notice from Lenz herself.

This was possible because the DMCA provides a “safe harbor” for web hosts, such as YouTube. It prevents hosts from being liable for infringements committed by their users so long as they work expeditiously to remove infringements when they are properly notified. To guard against the DMCA being used to silence non-infringing speech, the law has provisions that allow a plaintiff to not only file a counter-notice and get wrongly removed content restored, but to sue when they feel that a notice was filed in bad faith.

That, in turn, is the issue here. Whether or not Universal acted in bad faith when they filed the DMCA notice. Lenz claims that the video was a clear non-infringing fair use. Universal has repeatedly stated in court that they do not feel it’s a fair use but, more to the point, that they were not obligated to consider fair use at all before filing the notice.

However, the Ninth Circuit has taken up that latter issue and decided that rightsholders do need to consider fair use before filing a notice, an announcement that has sent shock waves through some copyright circles, even though the importance of this ruling is, most likely, greatly exaggerated in the media.

The DMCA and Good Faith

Understanding the ruling is fairly complicated, but to really understand it we have to put it into context of another Ninth Circuit decision, this one from 2004, Rossi vs. the Motion Picture Association of America.

Understanding the ruling is fairly complicated, but to really understand it we have to put it into context of another Ninth Circuit decision, this one from 2004, Rossi vs. the Motion Picture Association of America.

At the time Rossi ran a site named InternetmMovies.com. The site made widespread promises about “full downloads” of Hollywood films but, much like many similar sites, actually didn’t have any films for download. Instead, it was just a scam site designed to trick people into clicking on ads.

The MPAA however, seeing the promises of their films for download, filed DMCA notices and eventually got the site booted from its host. Though the site was able to move to a new host with almost no down time, Rossi sued the MPAA, claiming (among other things) that the organization had violated the DMCA’s “good faith” clause noting that, if the organization had just attempted to download the films, they would have known there was no copyright infringing material.

The district court and the Ninth Circuit, however, disagreed. In the Night Circuit ruling, the court said that Rossi gave the MPAA (and others) plenty of reason to think that infringing files were there and that the standard for good faith when filing a DMCA notice is subjective, meaning it’s a matter of the state of mind of the filer, rather than objective, which looks at the person’s actions.

As such, since the MPAA clearly had subjective good faith, the court awarded summary judgment to the MPAA, never letting the issue reach a trial.

Now, 11 years later, we’re revisiting this case (in the same circuit no less) but from the vantage point of fair use. There, the court has ruled in the Lenz case that rightsholders do need to consider fair use before filing a notice, that the power to remove content from the web must be checked by requiring rightsholders to consider fair use.

But the court admits that the obligation is fairly limited, in the Lenz ruling the court said,

[A] copyright holder’s consideration of fair use need not be searching or intensive. We follow Rossi’s guidance that formation of a subjective good faith belief does not require investigation of the allegedly infringing content. . . .

In short, the fair use analysis doesn’t need to be accurate or even thorough. Rather, it just has to take place at some point.

So, even though the ruling does require that rightsholders consider fair use before sending off a notice, most likely, nearly all DMCA filers is meeting the requirements already.

Why the Ruling Isn’t a Complete Victory

It’s important to note that this ruling is not the end of the case. The ruling just makes it so that there is a triable issue as to whether or not Universal considered fair use when filing its notice.

Lenz argues that the video is such a clear fair use that there is no practical way they could have considered fair use and filed the takedown. Universal in court, however, still decline to concede that the video is not a fair use. But that claim goes most experts, including the Ninth Circuit, which seem to disagree.

If Lenz can not prove that Universal failed to consider fair use, then the case still could easily be decided in favor of Universal. This ruling makes it clear that it’s not important that Universal be correct in its analysis, just that they made consideration to fair use before filing, even if it was wrong.

(Note: It should be pointed out that Universal admitted it did not consider fair use directly before filing the notice, but said that it performed other tests on the video that it claims amounted to a fair use test.)

But even if Lenz does win, the case could wind up being a huge net loss. The case has been litigated for eight years already and, as the Ninth Circuit ruled, she is only eligible for nominal damages. Since she wasn’t financially harmed by the removal, a previous ruling said she can only collect a small fraction of attorney fees and very small damages.

The appeals court didn’t weigh whether additional attorneys fees were warranted in this case.

While Lenz, who is backed by the EFF and others working on her case for free, can certainly continue this fight without worrying about collecting those damages, others can’t. If a lawsuit over DMCA abuse isn’t practical because of financial reasons, it doesn’t matter what rulings are secured.

In short, it doesn’t matter if the EFF clears a path if no one else can afford to follow it. But, as we said above, Lenz and her lawyers still have a very long way to go to finish the path.

Who Does the Ruling Impact?

The ruling could, in theory, have a major impact on rightsholders who file DMCA takedown notices and the people/services who protect them. That includes, at least theoretically, myself as I provide such services at CopyByte.

However, relatively small filers such as myself aren’t drastically likely to feel any impact. The reason is because we already weigh fair use when filing DMCA notices. Either we’re dealing with clear non-fair uses, such as outright piracy, revenge porn or widespread verbatim plagiarism, or cases that can be trivially shown to not be a fair use.

Compound this with simple rules which are designed to both prioritize cases and prevent DMCA notices targeting fair uses, I feel pretty confident that I am safe as are most others like me.

Theoretically, the issue is more targeted at large scale DMCA filers, such as those who use bots to automatically track pirated content or simply use large numbers of employees to track and file for removal of infringing work.

When computers take control of the DMCA process, mistakes happen. We routinely hear stories like the recent one involving Vimeo and the movie Pixels, where non-infringing videos with the same name were removed.

But while this ruling may seem like a shot across the bow of companies that use such tools, it isn’t. In fact, it’s actually welcoming of the use of automated tools, saying that:

We note, without passing judgment, that the implementation of computer algorithms appears to be a valid and good faith middle ground for processing a plethora of content while still meeting the DMCA’s requirements to somehow consider fair use.

In short, as long as the algorithm set up to find the content weighs fair use in some way, it too is probably fine.

So, in truth, this ruling doesn’t appear to be making any attempt to stop automated DMCA enforcement. Instead, it’s trying to ensure that automated tools weigh fair use the same as people should.

So, instead of bringing an end to automated DMCA enforcement, it may actually encourage it over the long run by providing greater legal certainty to the process.

Bottom Line

If you’ve been filing DMCA notices, you should have been considering fair use even before today. I was even talking about it in 2010 when listing reasons you would not want to file a DMCA notice.

If this ruling forces you to drastically rethink your DMCA strategy, then you likely were doing something questionable before. Considering fair use isn’t just the legal thing to do, it’s also the ethical thing to do.

After all, this ruling is not opposed to automated takedowns and it isn’t even a warning against filing notices where there might be a fair use question. It’s just that you have to consider fair use and, along with the rest of your good faith belief, believe that it is an infringement.

While I understand why many are either celebrating or loathing this ruling, I don’t see it as a watershed moment for the DMCA one way or another. Especially when you consider that the case is a long way from over and it’s still very possible Lenz could lose, either directly or via a pyrrhic victory that erases this ruling from practical application.

And that’s the main point at the end of the day, the ruling doesn’t make false DMCA lawsuits any more practical and the case, in total, could make them even less so.

While this is certainly a victory for Lenz and the EFF, it’s likely it won’t have much broader impact. That could change depending on how the rest of the case goes, but the issues of cost of filing a lawsuit, meager damages, difficulty proving bad faith and the size difference between major rightsholders and the average netizen are still very real challenges that few can overcome.

DMCA filers should absolutely use this as an opportunity to check their own fair use policies and ensure they’re doing the right thing, but, beyond that, there’s not much that can or should be done.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.