20 Years Later: Metallica v. Napster, Inc.

Fight Fire with Fire...

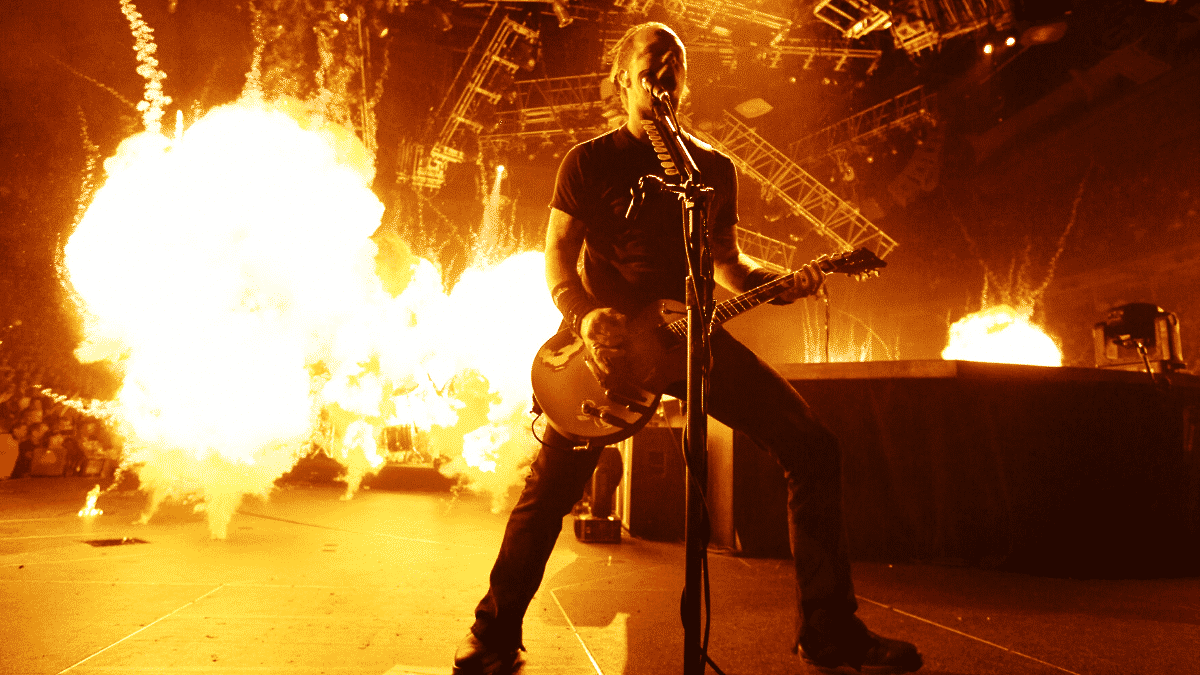

Twenty years ago today, on April 13, 2000, Metallica filed a lawsuit against Napster over its music-sharing service. The story immediately made headlines all over the world as Napster had become incredibly popular in a very short period of time and Metallica was (and still is) one of the biggest musical acts on the planet.

According to popular lore, this lawsuit was the beginning of the end of the original Napster, eventually forcing Napster to shut down on July 11, 2001. Many believe to this day that it was James Hetfield and Lars Ulrich themselves that dug Napster’s grave.

However, that is not actually what happened.

The Metallica lawsuit was actually three months late. On December 6, 1999, a consortium of 18 different record labels filed their lawsuit against Napster in a case that is goes by the name A&M Music v. Napster, Inc. That would be the lawsuit that would actually seal Napster’s fate, including obtaining the injunction that would eventually close the original Napster for good.

(Note: Though all of the labels involved in the A&M case were members of the RIAA, the RIAA itself was not a plaintiff.)

However, back in 1999, the RIAA was a little-known trade group and a lawsuit by a group of record labels largely slipped under the radar. It was the Metallica lawsuit that grabbed both the headlines and the public’s imagination. Even if it didn’t change the course of Napster significantly, it definitely changed the discourse.

So, 20 years to the day of the lawsuit being filed, we’re taking a long look at the lawsuit that got the world talking about copyright law.

Hit the Lights

The original Napster launched on June 1, 1999. Fueled by the rising popularity of the MP3 file format, the service offered an easy way to search for, download and share music files.

Though it wasn’t the first tool for sharing MP3 files, private and public FTP servers had been used before Napster’s launch, it was the first to make the process both easy, free and broadly accessible. Napster especially caught fire on college campuses where access to high-speed connections made the service fast and convenient, even if the service taxed some networks.

While the record labels would file their lawsuit in December, Napster went unnoticed by the members of Metallica until some time in early 2000 when Metallica learned that a song they were actively working on, I Disappear, was being played on the radio. The track was intended to be released in August as part of the Mission: Impossible 2 soundtrack but was getting radio play even as they were still in the studio recording it.

The band traced the song back to Napster, where early versions of it had leaked and were then picked up by radio stations.

This prompted Metallica, in what Lars Ulrich would describe as an “impulsive” move, to file its now-famous lawsuit in March 2000. There, they sued not just for the infringement of I Disappear, but for a total of 100 tracks. They sought a minimum of $10 million in damages, amounting to $100,000 per song. The band also targeted three universities, The University of Southern California, Yale University and Indiana University, noting that they had done nothing to block access to Napster on their networks.

Napster ended up doing some blocking of its own as, in May 2000, lawyers representing Metallica turned over some 60,000 pages of documents that identified some 335,435 users that were illegally sharing their Music. The users identified were eventually banned though a simple workaround for the ban was quickly discovered by users.

But, even as the case was winding its way through the courts. Another trial was taking place in the court of public opinion. There, seemingly, a verdict had already been reached.

Napster… Bad!

To call the lawsuit controversial would be a grand understatement. Napster and the lure of free, easy-to-access music was very popular and, for many, Metallica was raining on the parade. Worrying about copyright was not very rock and roll and seemed antithetical to Metallica’s branding as heavy metal icons.

The mockery was swift and probably best illustrated by a series of animated videos produced by the online group Camp Chaos. The first video, Napster Bad, came out in May 2000 and featured a Frankenstein’s monster-like James Hetfield and a hyperactive Lars Ulrich opining the evils of MP3 sharing. Later episodes would continue the trope and even expand the “universe” to a small cast of characters.

The Camp Chaos videos can be described as early viral videos. Though YouTube was still half a decade away, these videos were shared widely and viewed millions of times.

Despite the backlash, Metallica didn’t shy away from the controversy. In July 2000, Lars Ulrich testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee in a hearing about the future of digital music. Also, while Metallica was definitely the most well-known band to target Napster, they were not alone. Other musicians including Dr. Dre, who had filed his own lawsuit against Napster, Madonna, Elton John and others also publicly came out against Napster.

However, Napster also represented something of a divide among musicians. Where some acts saw Napster as a threat, others saw it as an opportunity. Limp Bizkit singer Fred Durst came out in support of Napster in an April 2000 interview. Interestingly, he was an A&R executive at Interscope/Geffen/A&M, the titular plaintiff in the original Napster lawsuit.

But perhaps most interesting as Motley Crue. The band not only came out in support of Napster, throwing several insults toward Metallica along the way, but had Camp Chaos create the official music video for their 2000 single Hell on High Heels. It was a bold statement to say the least.

Ultimately though, the matter wasn’t going to be decided in the court of public opinion. Rather, it was going to be handled in a court of law. There, things would come to a much less animated and much more serious conclusion.

…And Justice for All

Inevitably, Metallica’s case against Napster would be decided by the A&M case. It was first to court and would be the one that would set the tone.

In August 2000, the District Court of Northern California issued a preliminary injunction against Napster that barred Napster from “Engaging in, or facilitating others in copying, downloading, uploading, transmitting, or distributing plaintiffs’ copyrighted musical compositions and sound recordings.”

Given that the lawsuit was filed by 18 record labels, they claimed to own some 70% of the music being shared on Napster at the time. This was a figure that the court agreed with when granting the injunction.

Napster appealed the injunction to the Ninth Circuit and, on February 12, 2001, the court upheld the injunction. Though the court did say the original injunction was overly broad and sent it back to the lower court to be reworked, it ultimately agreed with the logic for granting the preliminary injunction.

Metallica, for their part, cheered the appeal though Napster vowed to fight on.

However, the writing was on the wall for Napster and this was the beginning of the end.

In March 2001, the judge in the Metallica case issued an injunction that mirrored the one in the A&M case. Napster initially tried to comply with the injunctions using filters but was never able to do so to the satisfaction of the court.

At one point, Napster claimed to have achieved a 99.4% blockage rate of pirated content but the court said it was insufficient, wanting the number to be 100%. This led many to criticize the injunction as being too strict and even impossible.

This included Lawrence Lessig who said that, “If 99.4 percent is not good enough, then this is a war on file-sharing technologies, not a war on copyright infringement.”

Unable to comply with the injunction any other way, Napster shuttered on July 11, 2001. Though it initially planned to keep fighting and return, that never happened. Napster, in its original form, was done.

The company did settle with Metallica and Dr. Dre the next day, July 12, 2001. This came amid news that Bertelsmann AG was seeking to acquire the rights to Napster but the proposed deal was ultimately blocked by the courts over allegations that Napster CEO Konrad Hilbers, as a former Bertelsmann executive, had a foot on both sides of the deal.

Napster’s ultimate fate was bankruptcy, which it filed for on June 3, 2002, just one week after the planned acquisition was blocked.

Though Napster’s name would be acquired and it would relaunch as a legitimate music service, the original iteration was dead.

The Memory Remains

Twenty years later, Napster’s place in music and copyright history seems very secure. It was the first file-sharing lawsuit but it would not be the last. Even before Napster closed its doors, competitors and alternatives were springing up.

The piracy scene would go through phases. First, Napster clones dominated the landscape before pirates shifted to truly distributed networks, such as BitTorrent, before then moving on again, this time to streaming websites. Though old piracy platforms never truly die, the piracy landscape has moved far, far away from Napster. The reasons for this are both technological and legal in nature.

The music industry itself also changed a great deal 1999 was the biggest year for the global music industry. By 2014, the industry had lost 40% of its revenue. Since then, the industry has started to recover some but still remains more than 30% smaller than it was heading into the new millennium.

Some of this change was inevitable even without piracy. Even if every track on the internet had been legally-obtained, the internet was going to have a drastic impact on the way music is bought, sold and listened to. However, to say that widespread music piracy didn’t have an impact on the music industry is ludicrous.

While the exact numbers may not be knowable, in the decade between 2002 and 2012 we lost a significant percentage of working musicians. Even though things are starting to turn around at least some now, it’s hard to call it a comeback. The industry is still a shadow of its former self.

The ultimate legacy of Napster is that it began widespread music piracy. The legacy of widespread music piracy is the harm it’s done to the music industry. But, even in an era where there are multiple free, legal ways to access music, music piracy still exists and may even be on the rise.

Even as artists, producers and labels work to navigate the landscape that Napster left them, piracy still haunts them. To be fair, if it hadn’t been Napster, it would have been someone else. This story was always likely to play out. However, it ultimately was Napster and that will always be its place in history.

The End of the Line

In a 2013 interview with the Huffington Post, Lars Ulrich said:

“We weren’t quite prepared for the shitstorm that we became engulfed in… I think history has proved that we were somewhat right… It’ll be in the first five sentences of my obituary, and I sort of accept that.”

Metallica, ultimately, was proved at least partially right. Piracy was a threat to the music industry and, even if their approach didn’t win them any fans or actually change the outcome of the case, they did sound the alarm on it. As someone who was 19-21 and living on campus while all of this was going on, I can say that Metallica came across as Luddites to many as it was going down but they were ultimately shown to be looking farther ahead than most.

One of the things I found surprising reading all of these old news articles is how Napster is referred to as a “startup” and it was treated as if it were a legitimate company. If you launched a Napster-like service in 2020, you would be branded a pirate from almost day one. To use a comparison, even the Internet Archive has not been able to escape that label with its National Emergency Library.

The tide has shifted in our collective thinking about these issues. This is partly due to the legal victories but also due to better awareness and Metallica played a role in that awareness. They may have been mocked for it, but their stand let file sharers know that at least some artists were not happy with what they were doing. Twenty years later, there’s no (or at least very little) expectation or demand that artists will endorse piracy of their content. Artists have Metallica partly to thank for that.

Still, evolution in the fight against piracy was inevitable. Legal tactics have changed, with the RIAA and related organizations taking the lead and more criminal cases being brought. Metallica has since taken a backseat on piracy issues, and musicians rarely get their own hands dirty in such legal matters.

But, if you want to see exactly how much things have changed, take a moment to follow this link. There, you’ll be able to listen to Metallica’s I Disappear (or at least the first 30 seconds) on Napster completely legally. Twenty years ago today, this pairing kicked off a lawsuit that captivated the world.

Today, it’s just one track on a relatively-small music streaming service.

Metallica Image By: DallasFletcher – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.