Why So Many Photographers Hate Richard Prince

In late 2013 I found myself with a group of photographers at a conference. When I introduced myself as a person who worked in plagiarism and copyright, Richard Prince became the immediate focus of the discussion.

In late 2013 I found myself with a group of photographers at a conference. When I introduced myself as a person who worked in plagiarism and copyright, Richard Prince became the immediate focus of the discussion.

At that time, Prince’s victory in the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit was just months old. Photographer Patrick Cariou had sued Prince in alleging that Prince’s “Canal Zone” series of works were a copyright infringement.

To many photographers, the use seemed an obvious case of infringement. Prince had taken Cariou’s photos and modified them slightly, blotting out faces and adding some hand-drawn elements. However, Cariou’s work was still very recognizable and largely intact. Prince, however, argued that the use was a fair use and was allowed under the law.

The lower court had sided with Cariou, saying that the use was not transformative enough to be considered a fair use. However, the Second Circuit largely overturned that, ruling that most of Prince’s works were indeed a fair use and remanding a small number to the lower court for further hearings.

The case ended up being settled before a decision was reached on those works.

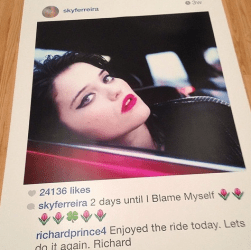

The case struck a deep chord with many photographers and artists frustrated by rampant misuse of their their content both off and online. So, when news came out today about Richard Prince’s latest exhibition at the Frieze Art Fair, which has him selling photographs from various Instagram users for up to $100,000, it reignited a firestorm against him as the comments on photography sites and social media show.

(Note: The original exhibit was at the Gagosian Gallery from September to October 2014)

But with so much infringement of photography, why is Richard Prince the lightning rod he is? To understand, we have to look at the bigger picture and where Prince fits in it.

The Photographer’s Struggle

As I discussed in 2013, photographers have a struggle that is unique among content creators.

Their work is widely shared and infringed upon but the tools for tracking it lag behind text or even audio/video. Photographers lack large, powerful labels or studios to lobby on their behalf, relying instead on smaller trade organizations and the rise of personal photography has made the photograph as a medium that feels transient and disposable to many viewers.

In short, photographers at all levels struggle to convey the value and worth of their craft, especially when it comes earning money from it.

Every photographer I speak with is aware of widespread misuse of their images online. In blogs, newspapers, web designs and even stock photo sites. However, they’re often at a loss as to what to do about. Enforcement costs time and/or money, both of which are tough to spend during difficult times.

Some have taken to following in Getty Images’ (and other companies’) footsteps and sending out invoices to commercial infringers, hoping to get their license fee plus additional costs.

It’s a difficult climate for photographers and the struggle isn’t getting any easier. But, even as photographers struggle, they often find artists making use of their work and finding great success based on it. However, Prince is far from the first to have faced that battle and the results have always been mixed for photographers.

Art and Appropriation

Artists and photographers have had many battles over the appropriation of pictures in other pieces of art. If there’s one thing that’s obvious from the history it’s that there is no simple way to determine what the outcome will be.

Artists and photographers have had many battles over the appropriation of pictures in other pieces of art. If there’s one thing that’s obvious from the history it’s that there is no simple way to determine what the outcome will be.

Consider the following examples:

- Andy Warhol: One of the best known examples of appropriation art turning litigious took place in 1964 when the famous artist Andy Warhol created the painting Flowers, which was a silkscreen based on a photo taken by Patricia Caulfield. Caulfield sued and won a cash settlement after she filed suit.

- Jeffrey Koons: Fifty years later in 2006, in a very different case, artist Jeffrey Koons used a photograph from photographer Andrew Blanch as part of his painting entitled Niagra. Niagra featured four sets of feet, one of which was the subject of Blanch’s photo. Koons ended up winning this case on the grounds that the use was highly transformative.

- Shepard Fairey: Finally, in the most famous non-Prince case of art appropriating photography, artist Shepard Fairey created the Obama “Hope” poster. In 2009 he was sued by the Associated Press, which claimed that Fairey has reused a photograph to create the painting. However, after Fairey submitted false evidence in the case, it began to go poorly for him forcing him to settle it on terms favorable to the AP.

In short, when artists reuse content from photographers, there’s a great deal of uncertainty and the outcome depends heavily on the specific facts of the case. But while most photographers accept that, many feel that the specific facts of Prince’s use don’t add up to the repercussions he has faced.

The Prince and the Pauper

Richard Prince has done very well for himself as an artist, making millions off of his work.

However, much of his millions have come from works that leaned heavily on the works of others and those photographers have not seen a cent for their involuntary contributions. Much like an architect who is paid handsomely for a building but fails to pay his suppliers and workers, Prince has earned a reputation as someone who has pulled from photographers without giving anything back (at a time when photographers are struggling).

To make matters worse, when he was challenged on it in court, Prince, for the most part, won. Though the decision remains highly controversial among copyright scholars, Prince vanquished the photographer and the decision could have dire implications for other photographers as they seek to protect their work with what they feel is overly broadened fair use exemptions.

To make matters worse, Prince has openly flaunted his relaxed views on copyright saying a 2011 interview that:

“Copyright has never interested me. For most of my life I owned half a stereo so there was no point in suing me, but that’s changed now and it’s interesting.”

He went on to say, speaking of Cariou:

So anyway, unfortunately I took too many of these Rastafarian (images) from this guy and I didn’t really even think to ask. I don’t think that way, it didn’t occur to me to ask him and even if I did and he said no, I still would have taken them. I figured I’d do them and maybe if he objected I’d deal with that later.

In short, even if he had asked and Cariou had said no, he would have used the images. Even putting aside the issue of copyright, many consider that deeply disrespectful to the photographer as an artist.

Where Warhol might have egregiously used the work of a photographer, he was quick to settle and pay out when challenged. Prince, on the other hand, has fought and won, making him despised among many who take photographs and view photography as an art unto itself.

Bottom Line

While Prince’s latest showing may have inflamed passions in photographers again, it’s unlikely there will be any repercussions for it. The one subject that has gone on record has said she has no plans on taking the matter to court and it’s very unlikely that any of the other photographers have the combination of interest, awareness and ability to do so.

Even with some of the photographs being of or by celebrities, a legal challenge seems unlikely, especially considering how protracted it would likely be.

Besides, at this point how much harm would a successful lawsuit impact Prince? He has achieved fame and wealth through his appropriation art already and a successful lawsuit or two won’t change that. At most it would unwind some of the Cariou decision.

For all of the outrage that Prince has gotten over his appropriation, it has given him exactly what he wanted, a name and a presence in the art world. It has made him a wild commercial success, regardless of what one thinks of his artistic merit.

So, while the anger toward Prince from photographers is understandable, it’s probably done more to further his career than hurt it. That, in turn, is probably a large part of why he is so frequently the target of anger and vitriol.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.