The Strange Copyright Case of the Game Genie

Like most people my age in the early 90s, I owned an Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), a decent library of games and, to go with it all, a Game Genie.

Like most people my age in the early 90s, I owned an Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), a decent library of games and, to go with it all, a Game Genie.

However, also like most people my age in the 90s, I was also completely unaware of the legal wrangling that took place over the Game Genie and, most importantly, how that dispute would come to affect copyright today.

The truth is that the Game Genie, perhaps unintentinoally, became an important test case for fair use and derivative works, creating an important ruling that’s still often cited today in seemingly unrelated cases.

Now, over 20 years later, we can look back at the case that was and see the role that the Game Genie played not only shaping gamers, but the bizarre place it has in modern copyright history.

About the Game Genie

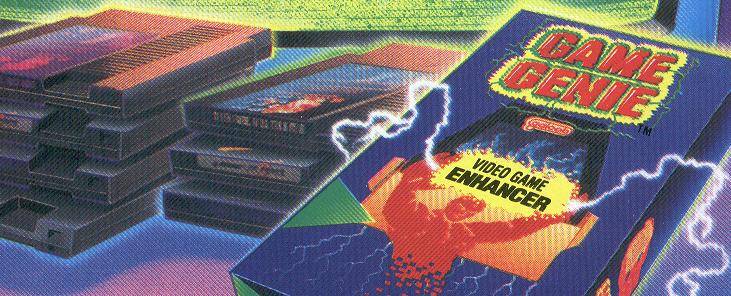

First introduced in 1990, the Game Genie was developed by a UK company named Codemasters and released in the US by Galoob toys, then one of the biggest toy companies in the world.

First introduced in 1990, the Game Genie was developed by a UK company named Codemasters and released in the US by Galoob toys, then one of the biggest toy companies in the world.

Billed as a “Game Enhancer”, the Game Genie was more often considered to be a “cheating device” as it allowed players to modify their games in a variety of ways, including providing infinite lives, unlimited ammo and allowing players to skip levels.

The Game Genie worked on a simple principle. The player would put the NES cartridge into the Game Genie and then slip the Game Genie into the NES. This meant the Game Genie was now sitting between the cartridge and the NES, where it was able to intercept and alter data exchanged between the two.

For example, if you died in an NES game, the chips in the cartridge game would take a life off and send a signal to the NES saying that you now had four lives instead of five. However, the Game Genie could intercept that and pass along that still had five lives, giving you unlimited lives.

This process was done through a series of codes that the user would enter upon starting the system. The codes were available inside a code book that came with the Game Genie, through a subscription to a special publication of updated codes, magazines and even user discovery.

The codes themselves were only temporary and didn’t modify the game permanently. Once you switched off the system, you would have to re-enter the codes if you wanted the same effects. Also, if you removed the Game Genie, the game returned to normal.

Despite this, Nintendo wasn’t happy about the prospect of players modifying games and took legal action against Galoob (as well as Camerica, which distributed the Canadian version) and set the stage for a copyright showdown.

Genie in a Legal Bottle

In 1990, Nintendo sued Galoob in a battle between two giant companies over the fate of the Game Genie.

According to Nintendo, the Game Genie was an infringement on Nintendo’s products, namely because, according to the Nintendo, the Game Genie created a derivative work or the original game, many of which were also made by Nintendo.

To back up its argument, Nintendo heavily cited Midway Manufacturing Co. v. Artic International, Inc., a 1982 case with many similarities.

In the Artic case, video game maker Midway sued Artic, which was making chips and circuit boards that infringed the copyright of two video arcade games, Pac-Man and Galaxian. Artic’s argument was that images in the video games were merely transitory and not fixed into a tangible medium of expression, thus they did not qualify for copyright protection.

However, the judge ruled against Artic, saying that the law does not require that the work be fixed into the the exact form it is perceived.

Obviously, Nintendo was keen to use this ruling, which was affirmed by the Seventh Circuit, in this case.

However, while the images and games were clearly copyrighted, the court took issue with the idea that Game Genie created a derivative work. The court found that, for a derivative work to be created, it had both incorporate the original work in a “concrete or permanent form” and it had to be able to stand alone.

Neither of these were true for the Game Genie.

The Game Genie required the original work to function and, thus, could not replace it. Furthermore, since the codes were temporary, there was no concrete or permanent incorporation.

The court also found that the use of the Game Genie by customers was a fair use. Since players were using the Game Genie for their personal enjoyment and there was no proof of economic harm to Nintendo, the court ruled in favor of Galoob there as well.

These findings were appealed by Nintendo to the Ninth Circuit but, in 1992, the court upheld the District Court ruling, paving the way for the Game Genie to be sold freely in the U.S.

Looking Ahead

As the “Legacy” section in the Wikipedia entry points out, the aftermath of the ruling has not been impressive. In one case, the fair use analysis was deemed to be non-binding and two other cases where it was referenced were concluded before a court could rule.

However, the legacy of the Game Genie may not yet be written. The device was one of the first consumer-oriented products to sit between two other devices and manipulate code in this way. Taking place well before the Internet was widespread, it’s easy to see how, theoretically at least, the ruling could have an impact on technology online.

Given the complex layers of interactions between applications, services and the increasing ways consumers are modifying copyrighted works, it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to see how the Game Genie ruling could come up again, especially considering that it’s in the copyright-heavy Ninth Circuit.

Still, the ruling hasn’t played a major ruling in any copyright case that I’ve been able to locate. But even if it’s never heard from again, it’s an interesting aside for both video games and copyright law.

Bottom Line

One of the challenges we face in copyright law is that much of the law itself was written well before the Internet existed or, at best, in a very different time for the Web. This can make it hard to see how new technology will be greeted by the old law and, often times, we have to find analogs that, while imperfect, can provide clues.

The Game Genie is an excellent analog for a lot of things taking place on the Web. After all, the Web is all about how layers interact with other layers. Consider how browser extensions manipulate Web pages or services use APIs to talk with one another. While much of this is done with legal certainty or even permission, much of the time it isn’t.

Though the case is an old one and, depending on the issue, others rulings may be more relevant, for those who want to show that their creation is not a derivative work and/or is a fair use, the Game Genie may live on.

It’s not the subject that’s important, but rather, the fact it was such a lopsided win in a battle fought by two giant companies.

In a legal environment where decisive victories are rare, this is definitely such a case.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.