How One Article Changed Fair Use

In March 1994, the Supreme Court of the United States handed down one of the most important decisions in modern copyright history: Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music

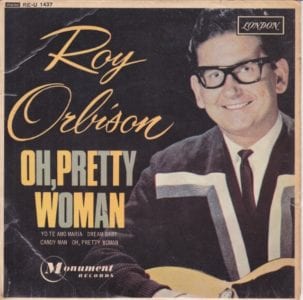

The case dealt with the band 2 Live Crew which, in January 1989, had released the song Pretty Woman, a parody of the 1964 Roy Orbison song Oh, Pretty Woman. Acuff-Rose Music, which held the rights to the composition of the Orbison song, filed a lawsuit claiming that the 2 Live Crew version was an infringement.

Though the district court initially ruled in favor of 2 Live Crew, the appeals court overturned that decision and said that the commercial nature of the parody gave it a presumption of unfairness. That decision was appealed to the Supreme Court, which was unanimous in ruling that there was no such presumption and that the parody could be fair use.

The case was remanded to the lower court, where the case was settled and the full terms were not disclosed.

The decision was a major turning point for copyright law, in particular for fair use. The 1841 case Folsom v. Marsh is widely viewed as the first fair use case and was the first decision to list the four factors of fair use that we know today (though they wouldn’t be codified into the law itself until 1976). The case put a heavy emphasis on the commercialization or commercial harm of an alleged infringement, making it the lead factor.

Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music undid that or at least severely blunted it. The commercial impact of alleged infringement was now just one of the factors weighed and a new factor, transformativeness, was taking center stage when determining fair use.

This shift has seen its share of both criticism and support, but one element of the story that often gets lost (especially to those outside of the legal field) is just how the decision was reached.

It’s very possible that the Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music would have turned out very differently if it had not been for one man who wrote one very influential article on the subject of fair use. It’s an article so prominent and important in fair use history that it was cited over a dozen times in the Campbell decision.

That man is then-District Court Judge Pierre N. Leval and the article was a 1990 piece in the Harvard Law Review entitled Toward a Fair Use Standard.

One Article, One Big Impact

As Terry Hart noted in his 2018 criticism of this article, the one thing that has remained consistent about fair use is that it is extremely inconsistent. It is a subject that is extremely divisive, even among the greatest minds in copyright, and it’s a topic where the more one learns and understands about it, the more difficult it becomes.

Leval, like many before and after him, was frustrated by fair use. Having two of his decisions overturned by the Second Circuit, he wrote the article in an attempt to create a new standard that he felt was more just and could be applied with greater consistency. To that end, he looked to the idea of transformativeness, saying quite bluntly that:

I believe the answer to the question of justification turns primarily on whether, and to what extent, the challenged use is transformative. The use must be productive and must employ the quoted matter in a different manner or for a different purpose from the original.

When he wrote the piece, he likely didn’t imagine that, just four years later, the Supreme Court would pluck that idea out of his article and apply it to what would become one of the most important fair use decisions in U.S. copyright history.

Though we can’t know for certain if the Campbell case would have gone differently without Leval’s article, the fact it was so heavily cited in the court’s ruling indicates that it had a strong influence on the justices and likely swayed the decision at least some.

And that influence would continue into the present day. Following the Supreme Court’s decision, lower courts began to alter how they approached fair use decisions. In 2011, law professor Neil Netanel published an article in the Lewis & Clark Law Review entitled Making Sense of Fair Use. That article presented data, captured since 2005, that showed “the transformative use paradigm has come overwhelmingly to dominate fair use doctrine, bringing to fruition a shift towards the transformative use doctrine that began a decade earlier.”

Transformativeness, for better or worse, had become the dominant factor in fair use discussions and that was owed largely to Leval’s article.

Criticisms of a Critical Shift

Leval’s intention with his article was to both bring greater certainty to fair use and to create a more balanced fair use standard. To that end, he was right to seek to improve the standard as fair use was not only inconsistent, but the focus on commercial impacts made it so that some parodies and commentaries, like the 2 Live Crew song, had little chance of being even seriously examined as possible fair uses.

However, it’s up for debate as to whether Leval and the push to transformativeness achieved that goal. Fair use is still wildly inconsistent. For example, in July 2018, a Virginia district court ruled that the permission-less use of images on a commercial website was a fair use simply because the images were cropped slightly. That decision was overturned by the Fourth Circuit but it still sent shockwaves through the photography community and served as a reminder of how unpredictable fair use cases can be.

Though the actual Campbell ruling doesn’t appear to be very controversial, the transformative standard has been used tor each some very divisive opinions. One of the prime examples is the 2013 case Cariou v. Prince, in which an “appropriation artist” made use of images taken by a photographer and minimally modified them. However, the Second Circuit ruled that the modifications were adequate to be seen as transformative and ruled the art to be fair use.

However, rulings such as Cariou can be blamed not on the transformativeness standard itself, but rather, an overly broad interpretation of it. Still, there’s not much doubt that a different standard would have yielded a different result in the Cariou case.

Ultimately the strongest criticism likely comes from the Seventh Circuit. There, in the 2014 case Kientiz v. Sconnie Nation LLC, a case that dealt with the use of a photograph on a shirt, the court scolded both sides for wasting so much time in debating how transformative the use was noting that transformativeness is “not one of the statutory factors.” Though the defendants ultimately won the case, it would not be because the use was or was not transformative.

In short, despite the Supreme Court ruling, there is still significant debate as to whether or not transformativeness is actually part of the law or just a weird metric favored by some circuits. That alone shoots down any of the consistency that one was hoping to get from this change in direction.

Indeed, as time has gone on, frustration and confusion over the transformativeness standard have only grown. As well-intentioned as it might have been, it seems to be causing many of the same problems as the previous standard.

Bottom Line

The story illustrates just how difficult fair use is. If any single standard becomes too important, confusion and questionable rulings become a serious problem. This harms everyone as creators are often unsure what their rights are critics as well as others seeking to use copyright-protected works can’t be certain what the boundaries are.

Fair use, works best when there’s a balance between all of the factors. However, that creates its own problem as it’s easy for two reasonable and intelligent people to look at the same set of facts and draw different conclusions. A balance between the factors brings inconsistency. However, focusing too heavily on one factor also brings inconsistency as interpretations of that factor can also vary.

There’s simply no way to get consistency out of fair use without bright-line rules. However, bright-line rules inevitably rob fair use of the flexibility that’s one of its best traits. There’s simply no way to have a fair use standard that is simple to understand, consistent in its application and achieves the goals of fair use.

Fair use is hard. There’s no way around it.

As for Leval, I doubt that he was aware of the near-immediate impact his article would have and how it would steer copyright moving forward. He clearly had the best of intentions and the idea itself wasn’t a bad one. Most of the problems with it are related to taking it too far and making it too dominant, not necessarily giving transformativeness greater consideration.

However, if you don’t like the current standard take some heart. It is almost inevitable that fair use will shift again. After all, the only thing consistent about fair use is its inconsistency. It is constantly changing, even right now.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.