As anyone who reads the 3 Count column (and pays attention to the puns) probably already knows, I’m a pretty serious Rocky Horror Picture Show fan.

As anyone who reads the 3 Count column (and pays attention to the puns) probably already knows, I’m a pretty serious Rocky Horror Picture Show fan.

However, the latest talk in the Rocky Horror community has been about the upcoming remake of the film, which is scheduled to debut on Fox this October. A teaser trailer for the reboot was just posted by Fox on YouTube as well as several photos of the cast and the set.

Unfortunately for Fox, the reboot plans have not been greeted with antic-i-pation by many Rocky Horror fans. Not only is the teaser trailer heavily disliked but there have been several campaigns (and petitions) calling on Fox to call off the remake.

Even the involvement of Tim Curry, the lead in both the original film and the original play, as the reboot’s Criminologist has not been enough to placate many in the community.

Those concerns are seemingly amplified by the detachment of Richard O’Brien, the original author of both the Rocky Horror Show and the Rocky Horror Picture Show and both the stage and screen’s original Riff-Raff.

But while I’m personally reserving judgment on the reboot until it airs, the situation did get me thinking a bit about the history of Rocky Horror, it’s copyright and about the larger questions of copyright, composers and musical films.

While there are a lot of things we can’t possibly know, there are more than a few things we can learn and understand, including how a remake is moving forward when the original author and composer doesn’t seem interested in it at all.

In short, while I can’t tell you everything, I can at least tell you where we stand.

A Brief History of The Rocky Horror Picture Show

From the day it was born, Rocky Horror wasn’t as a film, but a play. Specifically, it started out as a small production written by then out-of-work London theater actor Richard O’Brien, who drafted a rock musical entitled They Came From Denton High.

From the day it was born, Rocky Horror wasn’t as a film, but a play. Specifically, it started out as a small production written by then out-of-work London theater actor Richard O’Brien, who drafted a rock musical entitled They Came From Denton High.

O’Brien showed the play to a former director of his and the director gave O’Brien the chance to present the play at the small experimental space upstairs at the Royal Court Theater in the west side of London.

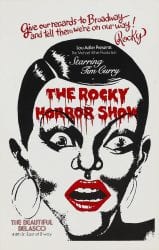

The play, re-dubbed The Rocky Horror Show, debuted in 1973 and was almost immediately a hit. It quickly moved to a larger space where it continued to sell out most nights and also rack up awards.

It was during that run that the play attracted the attention American record producer/songwriter Lou Adler who, after seeing a performance, secured the rights for an American performance, mounting a Los Angeles Run. Adler also was able to secure a film deal for the play, dubbed The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and filming began in England in October 1974, with about half the cast reprising their roles.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show opened in August of 1975 and almost immediately found a home with the midnight movie crowd. Audience participation grew and, in early 1977, the first “shadow cast” (the cast that pantomimes the film) appeared at the Fox Venice theater in Los Angeles.

Since then, the film has gone on to be a cult phenomenon best known for its heavy audience participation, midnight showings and decadence.

Why Owns Rocky Horror?

When it comes to who owns The Rocky Horror Picture Show, it’s pretty straightforward who owns it. Unfortunate for the sake of the puns, it’s not RKO, but instead, 20th Century Fox, the company that produced and distributed the film.

When it comes to who owns The Rocky Horror Picture Show, it’s pretty straightforward who owns it. Unfortunate for the sake of the puns, it’s not RKO, but instead, 20th Century Fox, the company that produced and distributed the film.

A quick search of the U.S. Copyright Office libraries shows that, other than a few mundane uses of the copyright (and other films as collateral) not much has happened with the rights. Furthermore, while the copyright registration for The Rocky Horror Picture Show is too old to be in the computerized United States Copyright Office database, the registration for its less-than-successful follow up, Shock Treatment, is.

There you can clearly see that 20th Century Fox is the copyright claimant and that the film is listed as a work-for-hire for the company.

All of this is fairly mundane for the movie industry. But there is one interesting wrinkle in the copyright of Rocky Horror and to be Frank, it’s a rather tender subject.

Going Back to the Play

As we discussed when we looked at the copyright of It’s a Wonderful Life, we learned that there are a lot of different elements to the copyright in the film. In that case, though the film itself lapsed into the public domain, the company behind it was able to secure the rights to the musical score and the story, giving it effective control over the work.

As we noted, Rocky Horror began life as a play written and composed by Richard O’Brien. Neither of those can be considered a work for hire wholly owned by Fox.

Now, it seems pretty clear that O’Brien sold Fox the film rights to the story and the rights haven’t reverted back yet. In addition to the upcoming reboot, Fox also did the Rocky Horror episode of Glee, which featured many elements from the play, including several of the songs.

However, O’Brien still retains the copyright to the play and the compositions in it. He can (and does) license and arrange performances of it. This includes a recent run in London that featured O’Brien himself as the narrator (known as the Criminologist in the film version).

If your theater wishes to perform the Rocky Horror Show, they can obtain a license to do so through Samuel French, which is a major licensor of musicals. Though they don’t list prices for the license, you can contact them either through their form or they may have a phone.

If you’re in a bar, restaurant or other business that wants to simply sing or play some of the songs, you can obtain the rights to do so through Richard O’Brien’s publisher, Wixen Music Publishing Inc. However, in reality, the entirety of the soundtrack is covered under a BMI license, which almost any establishment that plays music should already have.

Likewise, if you want to cover Rocky Horror songs and sell or otherwise distribute them, you can obtain a license through the Harry Fox Agency. However, mechanical licenses, as they are called, are covered under a statutory license. That means this is true for, more or less, all songs.

When all of this is said and done, even though Fox has the ability to move forward without permission from Richard O’Brien, it appears the copyright is quite safe. O’Brien retains a pretty large amount of protection over his creation and is still heavily involved in the theatrical side.

Bottom Line

What really struck me about the copyright of The Rocky Horror Picture Show was just how mundane it all is.

Rocky Horror is a film known for being at the fringes of society and of filmmaking. Whether it’s the camp, the themes of transvestism or the homage to B movies, nothing about this film is ordinary. That is, except the copyright and ownership.

The copyright situation, it seems, has more in common with Brad Majors and Janet Weiss than it does Dr. Frank N Furter. That’s likely done a great deal to help the film by giving legal certainty to all of the midnight showings and theaters that are hosting their own performances.

If there had been chaos, it’s unlikely that the film would have had the lasting impact it has. One only has to look to MovableType to see what happens when licensing is unclear.

Many may criticize the terms O’Brien agreed to when signing over the rights, saying he gave up too much control. However, a decision had to be made and it’s important to remember that, before writing Rocky Horror, O’Brien was unemployed and likely got the best deal he could.

But even then, Fox’s stewardship of Rocky Horror has only been called into question with the recent reboot.

For over 40 years Fox has largely let the fans guide Rocky Horror’s future and that’s what made it grow into the cult classic it is. It’s unlikely many other studios would have done that, especially given how lucrative it’s become.

So, sure, the reboot is a change of direction. But, at the end of the day, it’s just a jump to the left.

Note: As I said above, there are at least 10 Rocky Horror call out cues in this article. Anyone who can provide ten of them in the comments will get a tweet as the winner.

Also, happy anniversary Elli & Crystal!

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.