Parsing the Plagiarism of the Bad Art Friend

On Tuesday, journalist Robert Kolker published an article in the New York Times Magazine entitled Who is the Bad Art Friend? The story looked at the ongoing feud between two authors, Dawn Dorland and Sonya Larson.

To parse the winding tale into the most condensed version possible, the story begins when Dorland made the decision to donate a kidney to a stranger. As part of that act, she created a private Facebook group to share her experiences and Larson was among those in that group.

Larson would go on to pen a short story entitled The Kindest that was about a similar kidney donation/transplant. This prompted anger from Dorland as Larson never acknowledged the transplant but was working on a story about it.

However, as details of the case unfolded, Dorland learned that a donor’s letter she had written appeared in The Kindest, at least in part. This prompted Dorland to first report the alleged plagiarism to a wide variety of groups and worked on getting the story pulled while working through lawyers to demand financial compensation.

This eventually morphed into a legal battle when Larson filed a lawsuit against Dorland for defamation. That, in turn, prompted a counterclaim by Dorland for copyright infringement. Those cases continue even today but, as part of the legal battle, private chat records of Larson’s were subpoenaed that revealed she and her friends speaking very candidly, and cattily, about Dorland.

Almost immediately, the “Bad Art Friend” meme was born as people took to Facebook and Twitter to discuss the various ethical questions raised. Those questions come from every angle and include debates about social media, the ethics of organ donation, writers’ ethics when using elements from another person’s life and much, much more.

However, today, I want to focus on just one aspect of this story: The plagiarism.

Because, much like everything else in this story, the plagiarism question isn’t a simple black or white answer and one that is deserving of some additional attention.

The Basics of the Allegations

Though the plagiarism allegations are fairly complex, they come down to two separate major allegations:

- The Broad Concept: Broadly, Dorland accuses Larson of getting the idea for her story from her experiences and writing the story without talking to her about it, let alone get permission.

- The Letter: Doorland accuses Larson of copying her donor letter and including significant portions of it, in particular in early versions of the story.

To that end, both of those allegations are, in general, well-supported by the evidence. Larson has acknowledged that her idea for the story came from Dorland’s experiences but disputes whether that amounts to any form of plagiarism or wrongdoing.

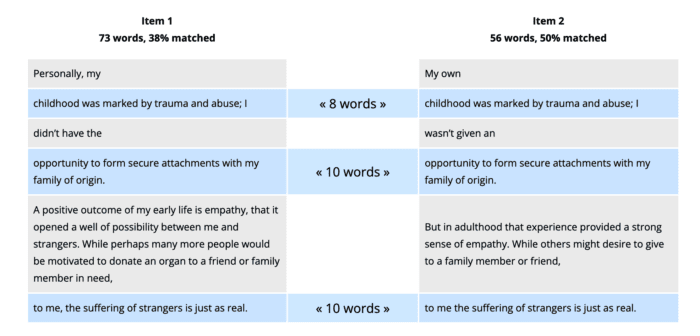

The letter is in a similar situation, comparison of the two letters clearly shows that they share a great deal of overlap.

Even a quick glance between the shows that key phrases are identical and, though much of the body is entirely changed, both the beginning and the end are either verbatim or close rewrites.

There cannot be much doubt that Larson’s letter was based on Dorland’s.

However, there’s not much dispute over what physically happened. The dispute is about the ethics of those actions and whether they amount to plagiarism or not.

Parsing the Shades of Gray

The letter issue, ultimately, is the much easier issue to parse. What Larson did there was clearly plagiarism. She took the words that someone else had written, copied them and used them in her story while presenting them as her work.

That is, in a word, unacceptable.

As a strong advocate of writing in a cleanroom, there was simply no reason for Larson to have ever pasted Dorland’s words into the story. Inspiration is one thing, but copying and rewriting exact words is another.

However, it is worth noting that the letter in question was drastically rewritten in later versions of the story. Still, the version above was published as part of an audiobook. Regardless of publication, the way it was incorporated into the story was plagiarism and there isn’t much of a way around that.

The broader issue about basing a story one another person’s experience. That issue, unfortunately for us, gets much more gray.

This is a much less explored question of writing ethics than traditional plagiarism or fabrication.

Five years ago, a poster on Quora asked this exact question and the replies they received were that it was not plagiarism. Historically, this question has been centered more around celebrities than laypeople. Unfortunately, that analogy doesn’t easily translate because celebrities, living and dead, have lower expectations for privacy, including in fiction.

In the original article, Larson gave an interesting example, “If I walk past my neighbor, and he’s planting petunias in the garden, and I think, Oh, it would be really interesting to include a character in my story who is planting petunias in the garden, do I have to go inform him…?”

However, the example is more than a bit glib. The answer to her question is obviously “No” because planting petunias is a common experience among millions of people and not one that’s likely to be deeply personal to the neighbor. Donating a kidney to a stranger is both much less common and much more personal. It speaks to the individual rather than the general.

But this doesn’t mean that Larson was in the wrong. This is especially true since, at least according to her friends, the original story was meant to be a teardown of Dorland’s actions. Does one need permission to criticize another through the medium of fiction? We don’t require it for non-fiction works. What would make a fictional deconstruction different?

Ultimately, there is no single answer here. Even if we all agreed that planting petunias is fine and kidney donations are not, we would likely disagree and argue over where the line is between those two things.

As such, we have to turn to the law if we want any clarity and, frankly, the news there isn’t good either.

The Legal View

To be clear, there are a myriad of potential legal issues that arise from converting a real-life person into a fictional character. However, none of them seem particularly applicable here.

Without reading the story, some guesswork is needed. However, if we assume that Larson changed enough of the details that it wasn’t Dorland’s story (or at least not hers alone) it likely won’t raise issues of privacy or libel issues.

However, perhaps most damming, is that the copyright question is likely to fail as well. .

First, it’s unlikely that Dorland registered the letter with the U.S. Copyright Office before the alleged infringement. As such, she is severely limited in the amount of damages she can claim and since Larson claims to have only earned $425 from the story, that may be the cap on damages.

But, even if she had such a registration, we are ultimately talking about 28 verbatim words and 56 words allegedly based upon it. That is very little and there could be many arguments that the use is not an infringement, that it is a fair use or simply that it is de minimis, meaning that the infringement is too small for the court to weigh in on.

While I don’t seem much debate that copying the letter was ethically bad, it likely doesn’t rise to the level of copyright infringement and, even if it does, the damages will likely be so small to make the lawsuit completely not worthwhile.

However, that may not really be important in this case. This isn’t a legal battle over recouping damages or settling some legal precedent, it’s a legal battle over hurt feelings and being more right.

To that end, the law itself may not be enough as, most likely neither of them will likely ever feel as if they’ve been made whole.

Bottom Line

If I were to speak to the two belligerents, I would have one simple question: Was it worth it?

While I can certainly understand Dorland being upset that her experience was the basis of a fictional story and I can also understand Larson being upset at Dorland taking offense, the response to this has been significantly disproportionate to the alleged harm.

What started as a relatively minor short story has grown into a major lawsuit with claims and counterclaims, a New York Times Magazine article and now an internet meme. It’s likely that both Dorland and Larson will be best remembered for this and not any other accomplishments they have made.

To quote the Metallica song Slither, “There ain’t no heroes here.” Both parties have contributed to the escalation of this otherwise minor disagreement, and now it is consuming both of their lives and their reputations.

It’s a cautionary tale of the true price of being right at all costs.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.