Understanding The JerryRigEverything/Casetify Copyright Battle

Last week, YouTuber Zack Nelson, better known as “JerryRigEverything” posted a video to his channel entitled simply “I’ve Been Robbed”.

The video discusses his Teardown line of phone cases, which he sells in partnership with dbrand. The cases are meant to be accurate representations of the internals of the phone, essentially making the phone look like it doesn’t have its back on.

However, the cases are not simply scans of the internals of various phones. Though Nelson made it clear that they work hard to make the cases as accurate as possible, they do take some creative liberties, such as making sure some components are visible when they might not be otherwise be and adding “Easter eggs” for fans of his channel and of dbrand.

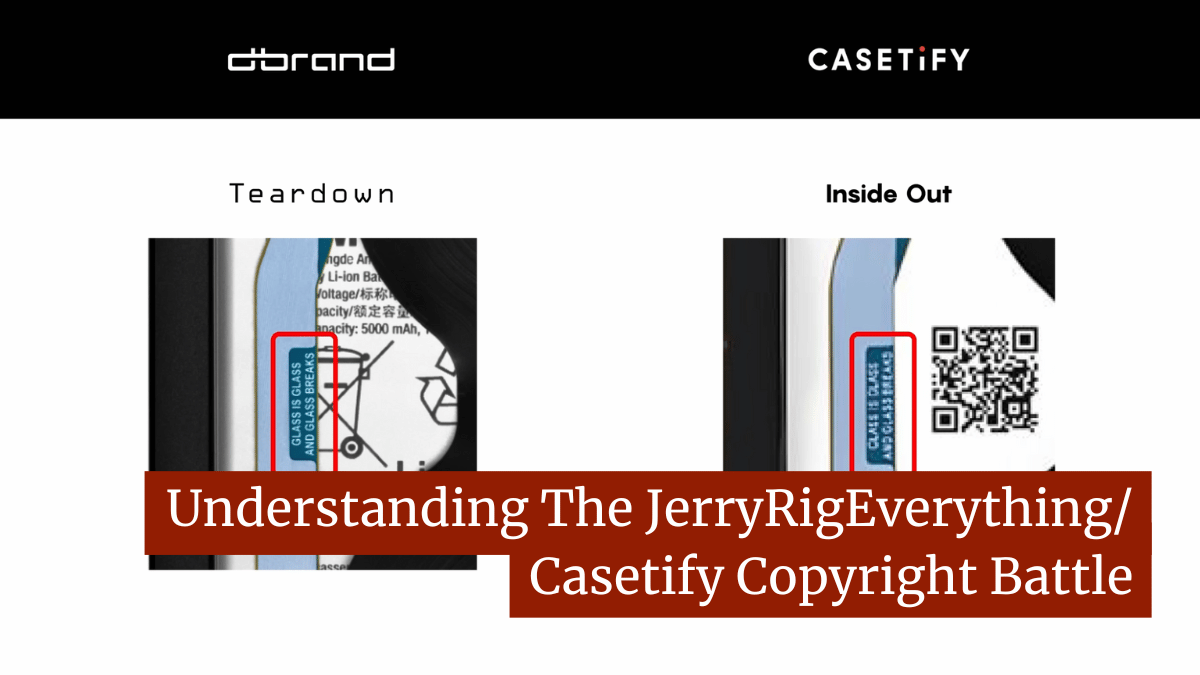

It’s those Easter eggs that become crucially important as, according to Nelson, another case manufacturer, Casetify, has been using his designs without either attribution or permission.

The proof of that copying is that, while some of those Easter eggs and identifying marks were removed, many were not. That included the inclusion of a tag that read, “GLASS IS GLASS AND GLASS BREAKS”, a common refrain on Nelson’s channel, hidden instances of the date 11/11/2011, the date of dbrand’s founding, being printed on items, and a pin that read “RO807” (Robot).

All these elements were duplicated by Casetify.

In addition to the alleged copying of Nelson’s work, Nelson also accused Casetify of copying a similar-themed PC case from iFixit. And then he accused them of using his iPhone designs to try and hide their copying of his other designs.

Casetify, for its part, responded to the allegations via X (Twitter). In their statement, they say they are a “bastion of originality” and that they are investigating the allegations. In the meantime, they claim to have removed all the designs from their platforms.

However, that likely isn’t going to stop the “multi-million dollar” lawsuit that was filed by Nelson in a Toronto courtroom. Though many of the details of the lawsuit aren’t known, Nelson has said that he is teaming with dbrand to file the case and plans to donate any proceeds he makes to his wheelchair manufacturing facility and to donate wheelchairs to others.

But this still raises the question: While it’s clear that the copying took place, did Casetify actually commit copyright infringement. The answer, most likely, is yes.

Maps, Easter Eggs and Copyright

Note: This case has been filed in Canada. However, most of my knowledge and most of my examples are from the US and UK. Though there is a great deal of overlap between the countries, especially in this area, there may be differences I am not aware of. Likewise, I am not a lawyer and nothing in this article should be considered legal advice.

Easter eggs have been a tool for catching copying for centuries. The best known use is by mapmakers, who would often add streets or other small errors into their maps to help them catch those that copied their maps rather than creating their own.

But, while it’s most commonly associated with mapmakers, the approach has been used in plenty of other industries as well. Antivirus makers add fake viruses to their databases, phone book publishers add fake names to their lists, and the lyric site Genius famous hid Easter Eggs in their lyrics to catch copying by Google.

However, in all these cases, the Easter eggs are there to prove copying, not copyright infringement. For example, though Genius sued Google for copyright infringement, they ended up losing the lawsuit because they don’t hold the copyright to the lyrics they were alleging were copied.

Even though they could prove that Google, or one of their partners, was copying from their site, they couldn’t protect the work at issue because they didn’t own it.

This is also a problem for mapmakers, phone book publishers and others. Even though they may have created the work in question, and thus own any rights in it, facts, ideas and mere information, even if gathered with a great deal of work, cannot be protected by copyright, just the creative expression of that information.

That creates a serious problem for mapmakers who, fundamentally, are primarily dealing with factual information. However, mapmakers have had some success in protecting their work.

For example, in the UK, the government agency Ordinance Survey won a £20m settlement from the Automobile Association over copied maps. That major win followed several smaller ones for the agency, the one before that being in 1995.

However, that was largely in part of the fact that Ordinance Survey’s “Easter eggs” dealt more with the styling and the way the data was presented rather than providing fake information. This meant that the copied elements were more creative and expressive, and thus protectable, prompting the settlement.

So where does this leave Nelson and dbrand? The answer is somewhat complicated.

Copyright and Phone Internals

As Nelson himself pointed out in his video, he does not own the right to the idea of creating phone cases based on the internals of the phone. That is simply an idea and not one that he, or anyone else, can own exclusively. Other manufacturers, such as iFixit, can and do make similar cases.

Likewise, he doesn’t own the internals of the phone either. Any copyright in those internals would go to the manufacturers. Even the fact that Nelson, or someone under his employ, took high-resolution photos or scans of the internals doesn’t grant him a copyright.

As the case Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp highlights, a photo of a public domain work is not protected by copyright unless there is some new creativity or expression added to the work. In short, if all Nelson did was open the back of a phone and scan, it’s unlikely that he would enjoy much, if any, protection in that either.

However, that’s not what Nelson does, at least according to his video.

Nelson creatively edits the works in two distinct ways. First, Nelson picks and chooses what components to remove and highlight. He specifically mentions uncovering the charging coil to make it “pop” more. However, he generally goes through and chooses what components to include, based on what he thinks will make the case the most aesthetically pleasing. This can include removing screws, ribbon cables or other elements that block the desired components.

Second, he adds Easter eggs and inside jokes such as the “GLASS IS GLASS” tag and other aforementioned referenced examples. These are sprinkled through the cases, giving fans of either dbrand or Nelson something that they, and they alone, will recognize.

You can actually see the difference in this article by The Verge, which puts dbrand’s original scan side by side with the edited Teardown case. A great deal of work goes into making the final product both look more visually appealing and to add those aforementioned details.

Those are creative and expressive elements that Nelson and dbrand can own. These elements were also clearly copied by Casetify and, to make matters worse, Casetify made obvious errors when doing the copying and clearly attempted to remove the Easter eggs that they did notice.

While it will be up to the court to decide just how much protection that this deserves, we are clearly not talking about just a simple scan of the device’s internals. Significant creative work went into enhancing those images to make them both more visually appealing and to cater to Nelson’s fans.

So while Nelson may have used a trick popularized by mapmakers and phone book publishers, his situation is a bit different. For him, his creativity has been copied, and there is definitely a much stronger copyright argument to be found here.

While we will have to see what the court decide, if they get the chance to, Nelson does seem to have some strong arguments, not just that he was copied, but that the copying amounts to copyright infringement.

Bottom Line

For Casetify, this has been an unmitigated disaster, one that hit right before the Black Friday weekend. As of this writing, Nelson’s video has more than five million views and the issue has seen widespread attention from both mainstream media and tech media.

Casetify’s response also did not go over very well either, with many mocking the “bastion of originality” claim. They also claim that they were hit with a DDOS attack that disrupted their website. However, many users on X (Twitter) are dubious of that claim as well.

The company is being roundly mocked for being a billion-dollar company that copies and plagiarized a much smaller competitor. However, that competitor happens to have a huge platform on YouTube, which has successfully turned the company into a laughingstock.

Regardless of what legal arguments Casetify may or may not have, the copying is completely clear. Even if they can win the lawsuit, it doesn’t change the fact that they were caught copying Nelson’s work.

Most likely, the best thing for them is to simply resolve the case as quickly as possible. Finding an amicable solution may give them a chance to rebuild their brand and leave this behind them. Meanwhile, ongoing litigation will simply remind everyone that they clearly copied Nelson’s work every time the story comes back up in the news. Any legal victory would, almost certainly, be Pyrrhic in nature.

At that point, the copyright arguments are almost moot. Though I feel Nelson has a strong case overall, it’s likely that the resolution will be motivated more by a desire to move on rather than the letter of the law.

Just because Casetify may have some legal arguments that could enable them to avoid or greatly reduce legal liability, that doesn’t mean they would be wise to pursue them.

Sometimes the best strategy is to just try and move on…

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.