The Courts are Losing Interest in Your Technology

Well, at least when it comes to copyright...

In February 2018, something happened that very few people outside of legal circles noticed. A district court ruled that embedding a tweet could be considered a copyright infringement.

The case centered on a photographer name Justin Goldman who took a photo of NFL quarterback Tom Brady walking with Boston Celtics general manager Danny Ainge. Goldman shared the image to his Snapchat Story but someone copied the image and put it on Twitter. From there, multiple news outlets embedded the tweet into their news coverage, prompting Goldman to sue.

After the district court ruling, the defendants tried to get an interlocutory appeal to the Second Circuit but that was denied. With the ruling standing for the time being and the prospect of a lengthy battle, most of the defendants in the case chose to settle. Eventually, so few remained that Goldman simply decided to drop the case.

While this might seem logical enough, photographer successfully sues over use of his image on news sites, it actually upended over a decade of legal theory.

Ever since 2007, courts have used what is known as the “server test” to determine who is liable for a particular infringement. The Electronic Frontier Foundation said it was a “clear and easy-to-administer rule” and one that “has been a foundation of the modern internet.”

However, that rule has been chipped at and courts are showing a growing disinterest in the technical machinations of how a product is made and are taking more interest in the final product.

To see why, we must first go back to where it all began.

A Perfect 10 for Google

In November 2004, Perfect 10, a pornographic website, filed a lawsuit against Google and Amazon for displaying unlawful copies of their images in search results. With Google, they took particular issue with two things:

- Google creating thumbnail versions of their images to display in search results.

- Google embedding and/or framing the infringing images from the original source in the search results.

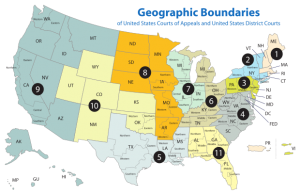

The lower court actually found that Google may be liable for the thumbnails since they were hosted directly on Google’s server. However, the court found the embedding was not likely an issue. Both sides appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and the court reversed the first part of the decision, ruling the thumbnails to be a fair use.

However, the Appeals Court upheld the part about embedding, ruling that an inline link (whether a framing or an embedding) was not the same as hosting the material, even if it appeared to end users that it was.

This created the “server test”, which basically states that the only party responsible for the infringement of a public display right is where the image is hosted. If another site embeds that content into their own page, they are not liable.

The decision came right at a time where embedding content was becoming more and more popular. YouTube and image sharing websites normalized embedding, which expanded to cover Twitter, Facebook and much, much more. If a rightsholder saw that their work was being used unlicensed, they had to deal with the source of the upload, not where it was being displayed.

However, in June 2014, a new decision was handed down, this one by the Supreme Court.

Aereo Killed the Video Star

Aereo was a TV streaming service that captured over the air broadcast television and streamed it to users over the internet. Normally, such a service would require a license but Aereo took a novel approach, having customers “rent” a single antenna that Aereo’s software would then manage.

Various television stations filed lawsuits and the case ended up all the way to the Supreme Court. There, the court made it clear that, “We do not see how this single difference, invisible to subscriber and broadcaster alike, could transform a system that is for all practical purposes a traditional cable system into ‘a copy shop that provides its patrons with a library card.'”

In short, the court found that invisible differences in Aereo didn’t change what it was or its liability. In essence, since Aereo walked like a duck, quacked like a duck and swam like a duck, the court treated it like a duck.

The case didn’t deal directly with the server rule. The server rule deals with liability of the display right of a copyright-protected work where Aereo looked at whether its broadcasts were public or private.

However, a seed had definitely been planted with Aereo and it’s a case heavily cited in the Goldman one. All totaled, the judge in the Goldman case, Judge Katherine Forrest, used the word “invisible” five times when ruling that embedding a tweet could be a copyright infringement.

To be clear, Judge Forrest didn’t tackle the server rule head on and didn’t say one way or another if it applied. Instead, she found that, “Even if the Server Test is rightfully applied in a case such as Perfect 10… it is inappropriate in cases such as those here.” She specifically noted the differences between a search engine and a news site in terms of user control.

But the Goldman case is far from the only one where resistance against these invisible systems have come up.

(Vid)Angel Brought Down to Earth

VidAngel, in its previous incarnation, was a movie streaming service that allowed users to “buy” a DVD for $20 and then stream through their service. They could then filter out unwanted content, such as nudity and violence, and then “sell” the DVD back for $19 when they were done.

The movie studios viewed this as an unlicensed movie streaming service and filed a lawsuit. The courts wasted little time in issuing an injunction against VidAngel and, earlier this week, a jury handed down a $62.4 million judgment against the company in a trial that only looked at damages.

The reason that the jury only looked at damages is because the judge had previously ruled that VidAngel was infringing. Though the summary judgment didn’t cite Aereo (the injunction order did but only because VidAngel tried to use it in its defense), it had much of the same logic.

The district court, as well as the Ninth Circuit when upholding the injunction, looked at how VidAngel operated. They noted that VidAngel marketed itself as a $1 streaming service, that 99.6% of its customers sold the DVDs back with an average time of just five hours and that the average VidAngel DVD was re-sold and re-streamed an average of 16 times in the first four weeks.

Though the rulings do take a look at the technical machinations of VidAngel (finding them to be infringing), much of the ruling is based on the “Walks like a duck” principle.

What we are seeing is a shift, albeit a slow one, away from emphasizing the tech itself in decisions and toward emphasizing what the tech actually does. This is far more useful because, as Aereo and VidAngel demonstrated, there’s always someone with a new approach and a new technology.

The courts, it seems, have grown weary of trying to keep up with these technical changes and are increasingly focused on what the product does and is meant to do. However, this doesn’t mean that the process of making this shift will be neat and easy.

With so much tech-centric precedent, it’s easy to see why the courts might struggle to make this change.

A Bumpy Road Ahead

In hindsight these changes may not be that surprising. In August 2008, barely a year after the Perfect 10 case, the Second Circuit issued in The Cartoon Network LP, LLLP v. CSC Holdings, Inc, often referred to as the Cablevision case.

The case looked at whether Cablevision’s remove DVR service was an infringement. The Appeals Court overturned a lower court ruling, found that remote DVR systems were not infringing. One of the key reasons for that was that, to the end user, the remove DVR system was functionally identically to an already-legal set-top DVR or even a VCR.

We do not believe that an RS-DVR customer is sufficiently distinguishable from a VCR user to impose liability as a direct infringer on a different party for copies that are made automatically upon that customer’s command.

Even though the verdict was lauded by many groups and individuals that support the idea of the server test, it defies the server test in its own way. After all, Perfect 10 put emphasis on where the material is stored, Cablevision said put the emphasis almost solely on the end result.

It should be no surprise that this case was heavily cited in the Aereo ruling including this passage: “Thus, in the example given above, the fact that the copy shop does not choose the content simply means that its culpability will be assessed using secondary-liability rules rather than direct-liability rules.”

The only problem is that the case, including that passage, were heavily cited in the dissent, not the opinion of the court.

That’s because, when you look at the technical machinations behind Aereo and Cablevision’s remove DVR, they share a great deal in common. The difference, ultimately, is that one was trying to recreate a DVR, a legal product, and the other was trying to create an unlicensed cable service, something far less legal.

Still, the road ahead is going to be bumpy and, if this trend holds, we’re going to see rulings that can feel inconsistent from a tech standpoint, even if they are consistent from an end user one.

Bottom Line

If a fashion reporter were covering this issue, I’d expect them to say something like, “Invisible differences and technical machinations are out, end user outcomes are in!”

Courts are increasingly shifting their focus away from how an outcome is reached and focusing on the outcome itself. This could have a great deal of impact not just on copyright law, but virtually any other area of law that technology touches.

If this trend holds it won’t be perfect or smooth. Like most trends in the law it will be one only visible over long stretches of time.

Indeed, trends like these are typically only visible in hindsight and, even right now, we’re likely only seeing the beginnings of it. There’s much more to this story, but it will unfold over the next few years and even decades.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.