How the EU Came to Govern the Internet

Turn your eyes toward Europe...

May 25, 2018 was something of a milestone for the internet. Countless sites and companies scrambled to update their sites, privacy policies and even their software to comply with a new law.

It was a day that saw inboxes across the globe flooded with updated privacy policies and newsletter re-confirmations. It reduced the effectiveness of the WHOIS system and is expected to rake in billions of fines from US tech companies.

However, the law wasn’t a US law, it was an EU law, specifically the GDPR.

Less than four months later, on September 12, 2018, the EU Parliament voted in favor of a new Copyright Directive that has the potential to radically change how copyright works on the internet. It would not only force tech companies to pay when they use even small portions of content from news providers and compel providers to be more proactive in preventing infringing works from being uploaded to their services.

However, that is just the beginning. On the same day as the Copyright Directive vote, the European Commission proposed new rules that could require internet providers to remove terrorist content within an hour or face fines. Likewise, the EU has been levying multi-billion dollar fines against US companies for anti-trust breaches, most notably against Google over its search and Android platforms.

When it comes to governing the internet, the EU has taken a much more aggressive stance. However, this isn’t a change that happened overnight, it’s been literally a decade in the making.

However, it’s a change that isn’t going to simply stop either and the EU, for better or worse, might be just getting started.

A (Very) Brief and Over-Simplified History

The United States’ history leadership in these areas is admittedly checkered at best. For example, the Berne Convention, one of the most important treaties for international harmonization of copyright, was originally signed in 1886 but the United States didn’t join until 1989, over a hundred years later.

However, with the rise of the internet, the United States began to take a much more active role in both impactful legislation and treaty negotiation. Not only did the U.S. quickly sign and implement the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights and the WIPO Copyright Treaty, but many of its laws began to have international impacts.

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA) of 1996 set the relationship between user and platform. In essence, it made it so that no provider of a service can be treated as the publisher or speaker of what their users say. This has been applied to defamation, discrimination and other areas of the law. The EU mirrored that approach with the Electronic Commerce Directive of 2000.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) of 1998 carved out the notice and takedown system that’s prevalent today. The approach was also largely copied by the European Union in the Electronic Commerce Directive of 2000. Other nations have also followed the example.

Other U.S. laws, such as the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003, also had a prominent presence on the international stage. In the case of CAN-SPAM, it was the undermining of stronger anti-spam laws in the EU and elsewhere.

The United States could do this because the lion’s share of major internet services are based in the country. Any law passed in the United States will immediately impact Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook, Apple, etc. Other countries can pass their own regulations, but these large companies can either shut down services, as with Google News in Spain in 2014, or simply exit the country altogether, as Google did with China in 2010.

In short, when the U.S. government spoke about the internet, it echoed throughout the world. However, those echoes have now largely stopped and much of it is owed to the fact that the United States stopped speaking.

The Giant Falls Asleep

As active as the United States was in the 1990s and early 2000s, it had largely fallen quiet by the mid-2000s. For a variety of reasons, the internet was not a focus of legislation in the United States.

Things began to ramp up again in 2010 with the Protecting Cyberspace as a National Asset Act and the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act (COICA). Things then reached a fever pitch in 2012 as the US Congress introduced both the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the Protect IP Act (PIPA), which both died after a public outcry largely spearheaded by efforts from major tech companies and related organizations.

However, the site blocking provisions, which were so controversial in SOPA and PIPA, have become the norm in many countries including Australia and the United Kingdom, and are being considered, with relatively little controversy, in many more.

Still, the SOPA/PIPA protests made the internet and copyright a hot button issue that a divided Congress wasn’t likely to approach again soon. Even a fairly innocuous 2013 bill that would have affirmed the US policy toward non-interference with the internet failed to pass.

The only major break in this silence came in March 2018 when the United States passed FOSTA-SESTA, an act that was aimed at reducing sex trafficking. Though the act may have broad impacts due to the poorly-written nature of the law, it was drafted mostly for a small number of sites that the US government saw was a problem.

Still, it was around the time of the SOPA/PIPA protests that the EU began to make its first big moves to regulate the internet.

The first such move to garter major attention was the “Right to Be Forgotten,” which was first proposed in January 2012. A broad version of that right was backed by a European court in March 2014, but eventually replaced by a more narrow “Right of Erasure” in the aforementioned GDPR, which was passed in April 2016 and took effect in May 2018.

However, that was just the first salvo. As radical as the GDPR was on privacy issues, so is the Copyright Directive on issues of copyright and the proposed obligations to remove terrorist content.

The EU, for better or worse, has taken a leading role in legislating the internet, making it the body to watch for privacy, intellectual property and freedom of speech issues online.

The Meaning of GAFA

The big difference between the US and EU when it comes to legislating the internet is that the EU has a very different relationship with the major US tech companies.

To make a very complicated situation simple: The US has traditionally sought to avoid burdening its major tech companies while the EU has, depending on your view, either a more neutral stance or an openly hostile one.

Legislators in the EU often use the acronym GAFA with a degree of mistrust. The acronym, which stands for Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple, got its start in France in 2014 as something of a slur for the US tech industry at large.

To that end, the EU’s complaints with the four companies in the GAFA acronym run deep. They include tax issues, privacy issues, compliance with EU law and general concerns about EU data being held in the United States.

While it’s unlikely that the GDPR and Copyright Directive were active attacks on US companies, it explains much about why the EU government is expressing little concern about protecting them from the impacts of that legislation.

In fact, according to a report by David Lowery at The Trichordist, lobbying efforts by US tech companies may have actively backfired in the recent Copyright Directive vote.

In a press conference about the vote, German MEP Helga Truepel was asked why the Parliament voted in favor of the directive in September when it had voted against it in July. She said,

“I think it’s due to this message spamming campaign. I talked to some of my colleagues here [and they] are totally pissed off, cause in the streets there were a maximum 500-800 people last Sunday… and we were only deleting emails for weeks now.”

In short, the massive email campaign, which was pushed by groups supporting and often funded by tech interests, angered many MEPs, especially given the limited in-person protests.

These are the same tactics that were so effective in 2012 against SOPA and PIPA. In 2018 they may have snatched defeat from the jaws of victory in the EU.

Simply put, the EU has shown it won’t look after US tech interests the way the US does/did. Unfortunately for those companies, they can’t afford to ignore the EU.

EU: Too Big, Too Important

US tech companies may be frustrated with the EU, but they can’t ignore it.

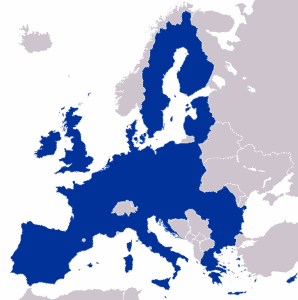

According to the latest available numbers, the EU has some 433+ million internet users. Compare that to just 312+ million in the US. Even with Brexit likely taking away some 62 million users, the EU will remain a juggernaut online.

Currently, the EU even has more Facebook users than the US, 252 million to 240 million (though Brexit will cost it 44 million Facebook users, pushing it below the US).

Though newspaper publisher Tronc Inc, owner of the LA Times and Chicago Tribune among others, made the decision to block EU countries after the GDPR, that isn’t a practical solution for the internet’s largest tech companies.

Even facing billions in fines and having to alter the way they handle privacy and copyright issues, the GAFA companies really don’t have a choice but to stay engaged.

This, in turn, is very much how the EU was supposed to work. Individually, any of these countries are small enough for tech giants to ignore. Google, for example, closed its Google News service in Spain after the country passed a law similar to Article 11, one that required Google to pay a license to news publishers.

However, as a 28-nation bloc, they can’t be ignored. Switching off the EU is simply too costly and may pave the way for EU-based competitors.

As such, major tech companies are, for the time being, going to have to deal with a mistrusting and very legislatively active EU.

Bottom Line

When the US fell largely quiet about legislating the internet, it opened the door for other governments to step in. The EU has taken that mantle largely because it is both willing to and is too big for major tech companies to ignore.

Whether it is using that power well or not is a separate question outside the scope of this post. What is clear is that the EU has become the governing body to watch when it comes to privacy, intellectual property and free speech issues online.

Willing to legislate, mistrusting of US tech interests and pushing a very different set of ideals than the US government had in the decades before, the EU has the potential to significantly reshape the internet.

In short, this is a story that is likely just beginning. 2018 may well wind up being just a warning of the major changes yet to come…

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.