Understanding the Star Trek: Discovery Plagiarism Allegations

Phasers set to litigate...

Update 1/11/19: I posted a video on YouTube discussing the recent motion to dismiss, you can view it here.

In late August, news began to come out that CBS and Netflix were being sued by Egyptian video game developer Anas Abdin for allegedly stealing his idea to create Star Trek: Discovery.

Though the lawsuit seemed to come out of nowhere, it had actually been a case nearly a year in the making. Abdin first posted about his allegations on his personal blog on October 18, 2017. In that post, he accused CBS (and others involved with Star Trek: Discovery), of taking ideas and even characters from his unreleased game, Tardigrades, and using it in the series.

According to Abdin, he had first posted the game on Steam Greenlight in May 2014 and posted constant development updates since. Star Trek: Discovery, on the other hand, debuted in September 2017 on CBS All Access (and Netflix internationally).

Abdin, in an August 2018 post announcing the lawsuit, said that he had attempted to work with CBS to address this issue “but they treated me in disrespect and just dangled me around with postponing meetings due to their vacations and being busy.”

But this raises the question: Is there anything to Abdin’s allegations or his lawsuit? The answer is “Probably not” but the case does highlight some interesting issues about the boundaries between independent creation, plagiarism and copyright infringement.

Understanding the Allegations

Tardigrades is an unreleased point-and-click adventure game about a civilization that existed 20,000 years ago and discovered that, through the use of giant tardigrades, they could travel anywhere in the universe.

Star Trek: Discovery is the latest series in the Star Trek universe. Set in the time between Star Trek: Enterprise and the original series, it explores the story of a cutting-edge ship named Discovery that is able to travel anywhere in the universe instantly through the use of its Spore Drive.

However, for several episodes in the first season, Discovery operated its Spore Drive with the aid of a giant blue tardigrade named “Ripper”, which had a symbiotic relationship with the spores and a connection to the mycelial network the drive uses. When it was discovered using it in the spore drive was causing it harm, the crew let Ripper go and a member of the crew took over the job.

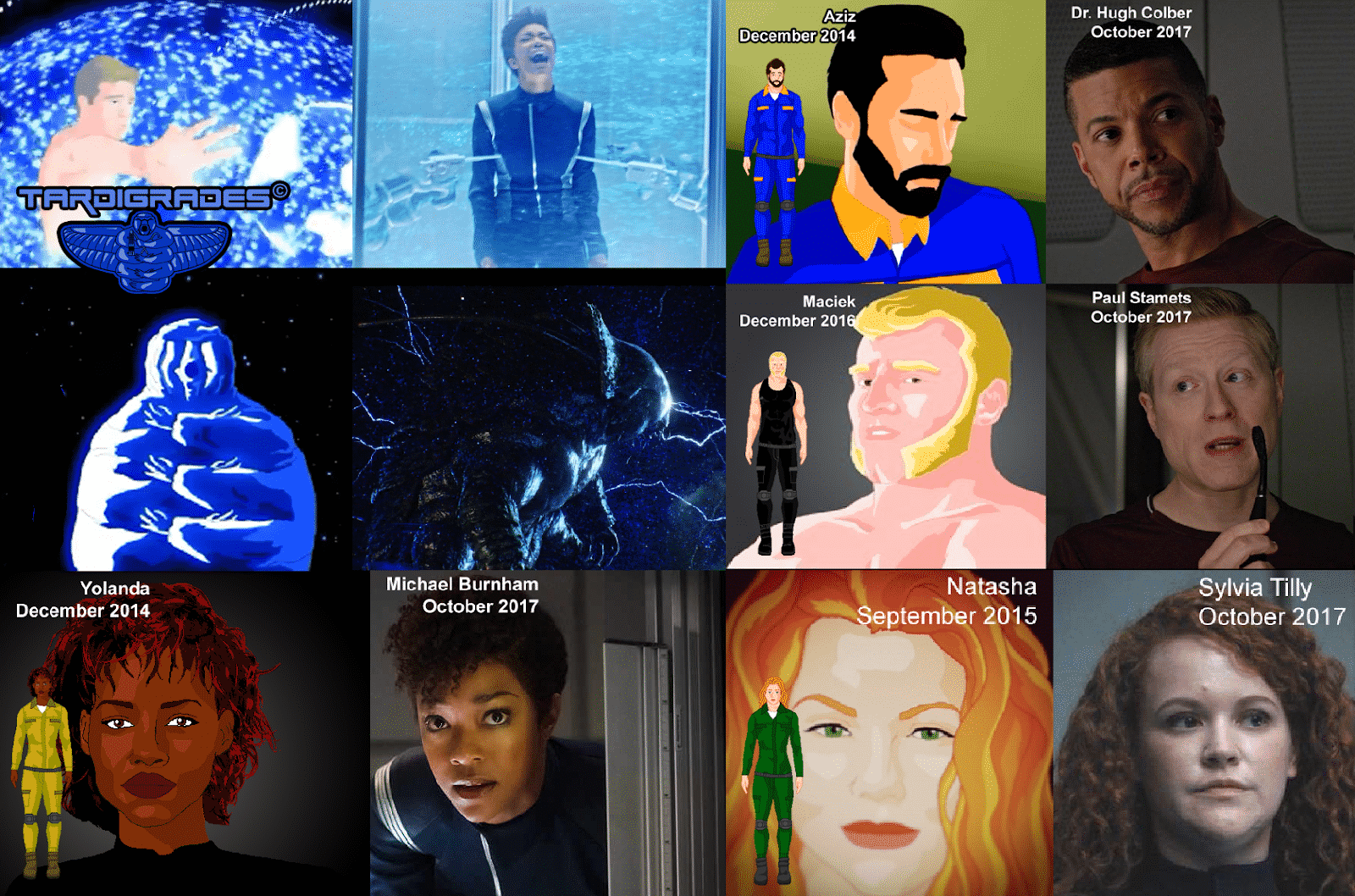

According to Abdin, the similarities between the two are just too much to ignore. The use of giant blue tardigrades to teleport anywhere in the universe is a striking similarity. Furthermore, Abdin claims that many of the characters in Star Trek: Discovery are similar to ones in his game, including an interracial gay couple. Couple that with some similar visuals, such as the inside of the Spore Drive vs. the inside of the Wormhole in Tardigrades and Abdin feels there’s enough to file a lawsuit.

This information has been enough to convince many. The comments on both Adbin’s blog and his Steam Greenlight page have been largely positive. Supporters of Abdin have been joined by critics of Star Trek: Discovery, which has been divisive among fans of other other series.

But does the lawsuit really have a chance? Probably not. Simply put, the lawsuit has to clear some gigantic hurdles and the odds just aren’t very good that it will.

Proving the Case

To prove his case, Abdin has to show two things:

- That the team from Star Trek: Discovery copied from him.

- That what they copied amounted to copyright infringement.

The first item will be difficult enough. Tardigrades was announced in May 2014. Star Trek: Discovery was announced in November 2015. Most likely, Star Trek: Discovery was in the works well before anything was made public about Tardigrades.

It’s also worth noting that Tardigrades are real creatures. They are microscopic organisms that have become somewhat famous in recent years for their ability to survive in space. In fact, in 2008 scientists from the European Space Agency subjected tardigrades to space-like conditions and they suffered no ill-effects. Tardigrades resiliency combined with their alien appearance make them natural fodder for science fiction.

Though it is an interesting coincidence that both used giant blue tardigrades to aid in instantaneous travel, the mechanisms by which they worked appear to be different. The tardigrade in Star Trek: Discovery functioned as a living computer and only worked at extreme peril to itself while, according of videos, Tardigrades has a more symbiotic relationship with their passengers.

But, even if it can be shown that CBS did copy from Tradigrades, Abdin has to prove that what was copied is protected by copyright. Simply put, ideas can not be copyright protected, only expressions of those ideas. You can’t sell copies of Harry Potter but you can write your own story about a child wizard that goes to a magic school.

Characters can be copyright protected, but only if they are distinct and original. In the case Litchfield v. Spielberg, a playwright sued claiming that an alien character he had created bore a strong resemblance to E.T. He noted that both characters were stranded on earth, had powers of levitation and telepathy and other similarities.

However, that case was dismissed with a summary judgment and that decision was upheld on appeal.

Given that tardigrades are real creatures, it seems unlikely that either CBS or Abdin would have protection in large, blue, space-traveling tardigrades.

The same is true for the other similarities. Having a black female lead or an interracial gay couple can be part of a character, but does not obtain copyright protection by itself. After all, these are elements in many, many stories and, if Star Trek: Discovery can be held liable for using, then Abdin would likely be in trouble as well.

While anything can happen to a case when it goes to court, this one will likely struggle to get past even the early stages.

So Why the Lawsuit?

If the similarities aren’t likely infringing and can be well explained by coincidence, why is there a lawsuit at all?

The reason was outlined pretty well in an article by John Walker for Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Abdin has been working on this game for years and his fans have been following his work for just as long.

When they saw Star Trek: Discovery, they saw something that felt very familiar. The similarities were striking. However, similar does not equal plagiarism and plagiarism does not equal copyright infringement. The gap between something being similar and it being infringing in the eyes of a court is huge. Far stronger cases have failed to meet those burdens.

Still, it’s hard to blame Abdin for feeling the way he does. Not only are the similarities noticeable, but Abdin has to know that, when he releases his game, many may accuse him of ripping off Star Trek: Discovery. This is in spite of the fact that it is demonstrably untrue.

I can’t imagine how that would feel as a creative and Abdin has my sympathies. He is simply in an unfair and

However, that doesn’t change the legal and practical realities of his case. While anything can happen in court, the odds are simply stacked against Abdin.

Bottom Line

When it’s all said and done, many people will never be convinced that Star Trek: Discovery is not a plagiarism. This is regardless of what evidence comes to light or how decisive the court rules.

To some, Star Trek: Discovery will simply never be innocent.

The truth is that the most likely explanation is that the similarities are mere coincidence. The counter explanation of CBS reading and stealing ideas from a relatively obscure, unreleased game just doesn’t add up.

When doing a plagiarism analysis, one of the tasks is proving not just similarity, but that the similarity cannot be dismissed by coincidence. To me, this doesn’t rise to that standard.

But, even if it isn’t coincidence and new evidence shows that clearly, that doesn’t mean it’s a copyright infringement. That is a separate test and a brand new challenge for Abdin to meet.

As sympathetic as I am to Abdin, his case is a long shot at best. With not one but two major hurdles in his path, the case is a reminder of how, while it can be easy to feel like you’ve been plagiarized, it’s much harder to prove it.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.