Copyright and Metropolis

The mediator between copyright and public domain must be the Supreme Court...

As Halloween approaches, you may find yourself seeking out a good horror or monster film. If you’re a copyright buff, you may find yourself seeking a good public domain film, of which I may have a few recommendations.

As Halloween approaches, you may find yourself seeking out a good horror or monster film. If you’re a copyright buff, you may find yourself seeking a good public domain film, of which I may have a few recommendations.

However, one film that is not on that list is Metropolis, a 1927 German expressionist piece that has become one of the most iconic and important works of cinema.

But while the film is definitely worth checking out, it didn’t make the list for the simple reason that it’s not in the public domain.

However, in the United States, that wasn’t always true. For a period of 43 years the film was in the public domain in the U.S. and it received a wide variety of re-releases, re-masterings and re-edits. But, due to a copyright treaty, the work fell back into copyright in 1996 and will remain there until 2022.

So how did this film lapse into the public domain and re-emerge as copyright protected? The answer, in many ways, is more strange than the tale the film itself aims to tell.

About Metropolis

Directed by Fritz Lang and released in 1927, Metropolis is one of the best-known and most iconic films of all times. A work of the silent era, the film is still hailed as one of the greatest and most important films of all time.

Directed by Fritz Lang and released in 1927, Metropolis is one of the best-known and most iconic films of all times. A work of the silent era, the film is still hailed as one of the greatest and most important films of all time.

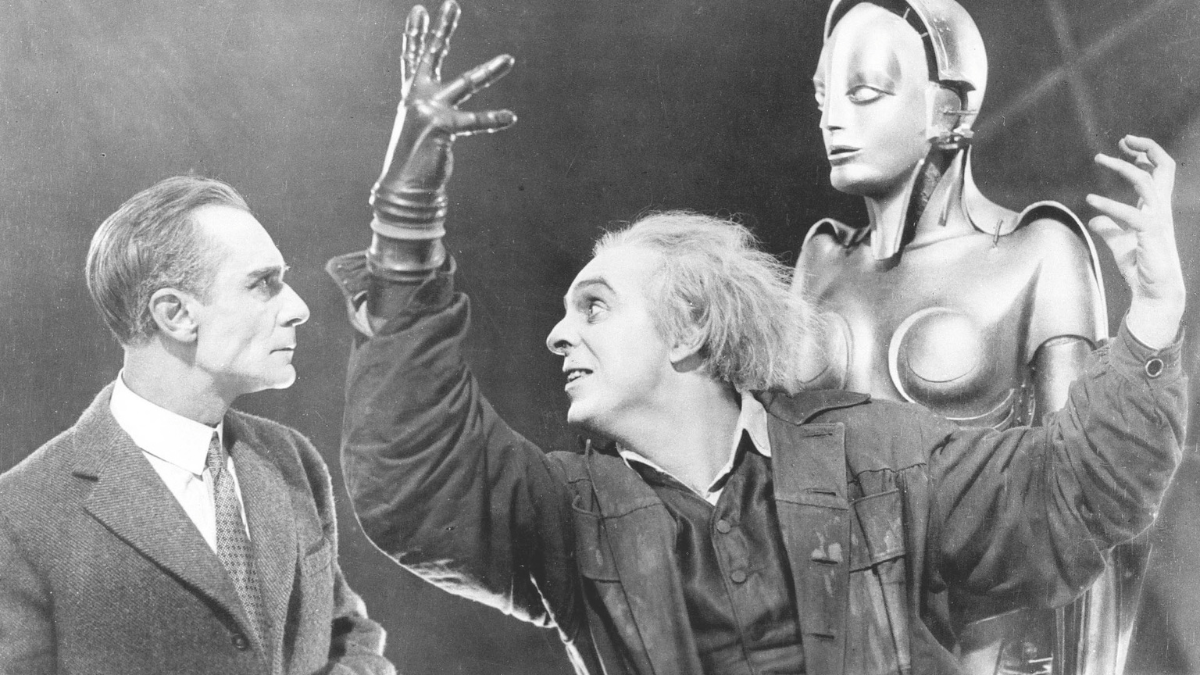

Metropolis tells the story of a deeply divided society. Wealthy capitalists who run the city live a life of luxury in towers while workers toil with the machines below the surface. Joh Fredersen is a wealthy capitalist who runs the city while his son, Freder, largely winds away his days in luxury.

But when Freder catches a glimpse of Maria, a woman who represents the workers, he becomes smitten and followers her. Under the city, Freder sees the horrors the workers suffer. Maria is attempting to rouse the workers into a revolt and Freder finds himself sympathetic to their cause.

Concerned about his position, Joh sends down a cyborg bearing Maria’s likeness to create trouble with the workers. The plan is successful and causes a great flood that requires the worker children be rescued. However, the workers strike back and destroy the cyborg as the scientist that created it is also killed.

Concerned about his position, Joh sends down a cyborg bearing Maria’s likeness to create trouble with the workers. The plan is successful and causes a great flood that requires the worker children be rescued. However, the workers strike back and destroy the cyborg as the scientist that created it is also killed.

Afterward, Freder assumes the role of the “heart”, serving as mediator between the “head” and the “hands”, bringing the film to a close.

To be frank, the plot of Metropolis doesn’t make a great deal of sense. It’s an ambitious story for a silent film and it’s further hindered by the fact that parts of the film have been lost. Even the best re-masterings only have about 95% of the film.

Despite that, the film has had a tremendous impact on modern culture. Not only is it considered to be one of the seminal monster flicks, but it helped inspire art deco design and had a huge impact on science fiction. From both a narrative and a stylistic standpoint, this film is a cornerstone of cinema.

But, if you’re thinking about remaking the film or re-releasing it, you might want to think twice. In the United States, the film is protected by copyright, even though that wasn’t always the case.

Metropolis: A U.S. Copyright History

Metropolis, though not released until 1927, was filmed and registered in 1925. Under the Copyright Act of 1909, the prevailing act at the time, the film was to be copyright protected for 28 years plus another 28 years upon re-registration.

Metropolis, though not released until 1927, was filmed and registered in 1925. Under the Copyright Act of 1909, the prevailing act at the time, the film was to be copyright protected for 28 years plus another 28 years upon re-registration.

However, that re-registration did not happen and copyright in the work lapsed in 1953. As a result of this, the film found itself amidst something of a renaissance with multiple re-releases. This included both theatrical and home movie re-releases over the decades.

But, on March 1, 1989, the U.S. formally joined the Berne Convention with the Berne Convention Implementation Act of 1988 entering into force. According to the treaty, the U.S. was supposed to grant copyright protection to foreign works that lapsed into the public domain due to lack of formalities, such as Metropolis.

However, the United States rejected the idea of doing this retroactively and only applied it to works created after the March 1, 1989. This led to an international condemnation of the decision.

In 1994, the U.S. signed the Marrakesh Agreement. That agreement established the World Trade Organization and was part of the Uruguay Round of negotiations. One of the elements of the agreement was that the United States agreed to place works back under copyright that it had failed to do so previously.

This led to the passing of the Uruguay Round Agreements Act (URAA) in in 1994. It took effect on January 1, 1995 though the copyright restorations didn’t take effect until January 1, 1996.

Under the URAA a work had to meet four criteria in order to have its copyright restored.

- Had to be under copyright in its source country as of January 1, 1996.

- Had lost its copyright due to non-compliance with formalities

- An author who was a citizen or domicile of the source country at time of publication

- Not been published in the US or published in the U.S within 30 days of publication in source country.

Metropolis met all of those requirements. It is protected by copyright in Germany until 2047, it was registered in the U.S. but not renewed, Fritz Lang (among others) lived in Germany during the production and it premiered in the U.S. on March 31, 1933, nearly two years after it’s German publication.

The law was clear, Metropolis was back under copyright. But that’s not quite the end of the story.

A Challenger Approaches

After the URAA took effect, many people who were making once-legal use of public domain works suddenly couldn’t any more. One of the most impacted groups were composers and musicians, who filed a class action lawsuit in 2001 known as Golan v. Ashcroft.

After the URAA took effect, many people who were making once-legal use of public domain works suddenly couldn’t any more. One of the most impacted groups were composers and musicians, who filed a class action lawsuit in 2001 known as Golan v. Ashcroft.

Their challenge was that the URAA was unconstitutional because it violated the clause that gives Congress the right to impose copyright and patent restrictions for a limited time.

The case was litigated for over a decade and ended up touching on a variety of questions, most prominently first amendment issues. According to the plaintiffs and the 10th circuit, the law needed a first amendment review.

However, on March 7, 2011, the Supreme Court granted certiorari and the case was heard on October 5, 2011 (by this point the case was known as Golan v. Holder).

Before the court was two questions:

- Does the Progress Clause of the U.S. Constitution prohibit Congress from taking works out of the public domain?

- Does Section 514 of the Uruguay Round Agreements Act violate the First Amendment of the United States Constitution?

The answer from the Supreme Court, which was handed down on January 18, 2012, was an emphatic “No” to both questions.

In a 6-2 decision, the court made it clear that Congress has the authority to remove works from the public domain saying the public domain is not “territory that works may never exit.” The court added that, in its view, there are adequate fair use protections built into copyright law to prevent a freedom of speech challenge.

As a result, the URAA was upheld and it remains law today. As such, Metropolis remains under copyright until 2022 and the copyright is held by the F.W. Murnau Foundation, a German organization that curates and preserves films from that era.

Bottom Line

Metropolis was just one of countless works that had its copyright restored under the URAA. While it’s certainly one of the most famous, millions of other works were similarly restored.

The move was highly controversial at the time, especially since it came not long before the Copyright Term Extension Act (URAA) of 1998, which added 20 years to the term of copyright in the U.S. Combined, the URAA and the CTEA are seen as the largest expansion of copyright in recent history.

Still, the case of Metropolis is an interesting one and, as with It’s a Wonderful Life, it’s a reminder that, once a work enters the public domain, it may not stay there forever.

This is especially true due to the copyright formalities that used to exist under U.S. law. Both Metropolis and It’s a Wonderful Life ran afoul of the re-registration formality. Any formality that can be legislated in can be legislated out (as with Metropolis) or altered by a court (as with It’s a Wonderful Life).

These two stories are cautionary tales for those who make use of public domain works. What’s in the public domain today may not be tomorrow.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.