What the Warhol Ruling May Mean for AI

Last week, the Supreme Court of the United States released its ruling in the case between the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and photographer Lynn Goldsmith.

As we looked at then, the case represents a rare ruling by the Supreme Court on the issue of fair use. Though the exact amount and direction of the change is yet to be determined, it is inevitable that this case will shift the way future fair use decisions are reached in lower courts.

To that end, the biggest fair use question in front of the lower courts right now is the issue of generative AI. Nearly every major player in the AI space is facing a copyright infringement lawsuit from one or more parties. This includes Stability AI, which is being sued by Getty Images and a pair of class action lawsuits that target GitHub, Midjourney and, once again, Stability AI.

However, those lawsuits have just begun and, as many have noted, we’re very much in the “wild west” days when it comes to AI and copyright.

With that in mind, it’s worth asking what the Warhol ruling may mean for AI moving forward. The answer is simple: AI companies should be worried about the Warhol decision, as none of its implications bode well for them.

A Brief Background

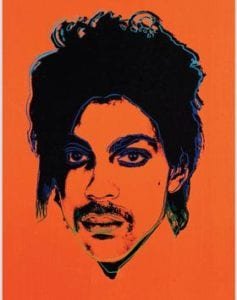

In 1981 photographer Lynn Goldsmith photographed the musician Prince. Three years later, she licensed one of those photos to Vanity Fair Magazine, who commissioned Andy Warhol to create a now-iconic painting of Prince for their cover.

Fast-forward to 2016, after the death of Prince, Vanity Fair then learned that Warhol had actually created a whole series of paintings based on the Goldsmith photograph. They then licensed one of those images, Orange Prince, from the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) for use on their commemorative cover.

However, Goldsmith claimed that Orange Prince (as well as the other paintings) were not licensed and were an infringement of her image. The AWF proactively sued Goldsmith, seeking a declaratory judgement of non-infringement.

The case ended up making it to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of Goldsmith. The court acknowledged that Warhol’s piece was transformative, but said that the piece competed directly with Goldsmith’s work and served as a replacement, citing the fact that Vanity Fair licensed the painting rather than Goldsmith’s original photo.

While seemingly a minor decision that follows the letter of fair use closely, it’s actually something of an upheaval in the way that fair use has been determined over the past few decades.

Ever since 1994, the question of transformativeness has been the primary and often the sole topic discussed in fair use cases. This has led to some controversial rulings involving artists like Richard Prince and Jeffrey Koons.

The issue of transformativeness took center stage following the case Campbell v. Acruff-Rose Music, better known as the Pretty Woman case. There, the band 2 Live Crew successfully argued that their parody of the Roy Orbison song Oh, Pretty Woman was a fair use.

The Warhol ruling, however, pulls back on that. It makes it clear that, while transformativeness is an important question, it is not the sole factor and not even the sole element of the first factor.

That, in turn, is why AI companies should be paying attention to this decision. Because it may have upended much of their legal theory on why AI is a fair use.

Why AI Should Be Worried

Generative AIs work by ingesting, or processing, large amounts of human-generated work and then training the model to create “new” work based upon that entered data.

Nearly all data that AIs have ingested, including text and image AIs, has been without permission from the original creators. This means that AIs are built on large volumes of copyright-protected material that they are using without permission.

However, AI companies have long argued that their use of that source material is allowed because it’s a fair use. Their argument for that, primarily, has been how transformative AI-generated works are.

Until last week, that argument seemed pretty solid, at least from a historical perspective. Given how much weight transformative uses were given in fair use analyses, and how transformative AI works are (at least when they are producing “original” content), it seemed likely that the argument would succeed.

The Warhol ruling, to put it simply, changes that.

By shifting the focus away from how transformative the use is, the Supreme Court devalued the best argument in favor of AI companies. Now, transformativeness must be contrasted with other elements, most notably how the new work competes with and/or replaces the original in the marketplace.

That, however, is not likely a discussion AI companies are eager to have. Stock photographers, for example, should have little trouble proving that the new works are used to compete with stock photos. Likewise, journalists should have no trouble showing how AI-generated text is used to replace news articles.

Things get even worse when you realize AIs often are tasked with producing works that are “in the style of” a particular creator, making works that are designed to directly compete with that artist’s work.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean that those suing AI companies are a lock to win. The issue is still complicated, and the Supreme Court made it clear that tranformativeness is still very much a factor and AI companies still have arguments in their favor.

However, the argument that AI companies have largely based their businesses around has been severely weakened, and that should give them pause.

What This Means Moving Forward

There’s a very good chance that the first major fair use cases after the Warhol ruling will involve AI. This raises a simple question, how will the courts interpret it?

Right now, there’s a wide range of thoughts on that. Some feel that this is a game-changing moment for fair use and that AI companies need to license their use as their fair use arguments are “discredited.” Others think that the Warhol decision will be interpreted narrowly as, like most fair use cases, the outcome was heavily fact-specific.

However, banking on a narrow interpretation seems, to me, to go against the history here. The Pretty Woman case, for example, was also meant to be a narrow ruling, but it’s literally dominated the fair use conversation for nearly 30 years.

More recently, the Supreme Court ruled in the Google v. Oracle case, with a deliberately narrow ruling that focused only on programming code and the facts of that specific dispute. However, we’ve already seen lower courts cite this ruling, including when it’s not directly applicable.

Simply put, lower courts have a bad track record of limiting the scope of a Supreme Court fair use decision, even when the Supreme Court expressly says they should.

What’s more likely is that courts will weigh this in comparison to the Pretty Woman case and try to determine if the issue before this is more like the first or the second.

The primary difference between them, at least when they look at the issue of how much to weight transformative use, is that the Pretty Woman case involved a parody that didn’t compete with or replace the original, and the Warhol case involved a stylized painting that clearly did.

So, does AI resemble the former or the latter? It depends heavily on the specific use. However, even if it does fall more to the latter, could AI’s transformativeness be enough to save it? That’s what the courts have to decide.

These are tough questions. But now they are questions. Two weeks ago, many, if not most fair use experts, felt AI had a clear upper hand. Now, the arguments in favor of AI are much more complicated and nuanced.

The Warhol ruling, by most accounts, has added a lot of complexity back to the issue of fair use, and no one is feeling that more strongly and more immediately than AI companies.

Bottom Line

We won’t really know what the impact of the Warhol ruling is until after the first courts begin to cite it. That, in turn, will likely take a few months.

However, what is unusual is that we have a major Supreme Court fair use decision just placed on the books and a major fair use question, one with significant implications, already on deck for it.

The Pretty Woman case, by contrast, was in 1994. The notable cases that leaned on it would largely come out years or even decades later. Here, it will likely be less than one year before we see newsworthy decisions referencing it.

One of the adages of the legal world is that the legal field is constantly lagging behind technology. While largely true, this may be one time when the law successfully cut off a technology by getting ahead of it.

Even if it was only by a few months…

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.