Copyright and Trademark in Professional Wrestling

The law behind the kayfabe...

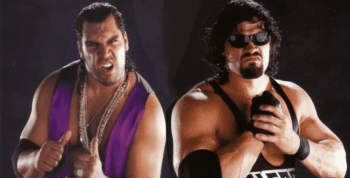

In the summer of 1996, things were looking pretty bad for the World Wrestling Federation (WWF) (Note: The name change to WWE would not take place until 2002). Their main rival World Championship Wrestling (WCW) had not only launched a competing Monday-night wrestling program but had just signed two of the WWF’s biggest stars, Diesel (real name Kevin Nash) and Razor Ramone (real name Scott Hall).

The two men would go on spark a glory period for WCW, launching the popular New World Order angle and lead to a period where WCW would dominate both the rations and interest.

So in August, it was a huge shock when WWF announcer Jim Ross announced that Diesel and Razor Ramon would be returning to the WWF. That promise came to fruition the next month when both characters would indeed appear. The costumes would be the same, the mannerisms nearly identical but instead of Kevin Nash and Scott Hall, it would be Glenn Jacobs (who would later find success as Kane) and Rick Bognar.

The move was reviled by fans. Though it’s unclear if it was a serious attempt to replace Nash and Hall with new wrestlers or just an attempt to rile fans, the reaction made it very clear: You couldn’t just swap out wrestlers and slot new ones into old roles.

But while this is seen as one of the low points in WWF/E history, it was also a turning point in how intellectual property was thought of both by fans, wrestling organizations and wrestlers themselves.

After all, the reason for this moment was because the WWF owned the trademarks and any copyrights related to those characters. They no longer had the men who portrayed them, but they tried to exploit the intellectual property around their creations nonetheless.

It failed, but both copyright and trademark have remained very important to professional wrestling ever since.

A Brief, Brief History of IP and Wrestling

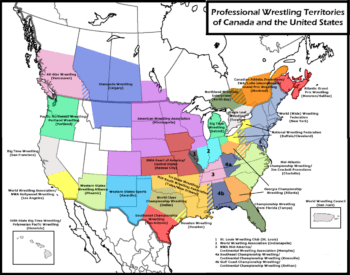

For much of the history of professional wrestling, the landscape was carved up into territories that were loosely affiliated under the National Wrestling Alliance.

During that time, wrestlers would often float from territory to territory, taking both their name and their gimmick (character) with them.

Though promotions would often repackage and reintroduce wrestlers under different names or gimmicks, there was little focus on controlling that through trademark or intellectual property. Some of that was due to the more cooperative nature of the territories and some of it simply due to keeping the predetermined nature of wrestling secret and not wanting to break “kayfabe”.

Though the promotions were fiercely protective of the things that contributed to their bottom line, namely their branding, their tape library and their merchandise, there was little effort to control or own what individual wrestlers did.

That began to change in the 80s as the WWF, through the use of cable television, began to expand nation-wide and led to more direct competition between promotions. This, after a series of mergers, buy-outs and closures, led to the WCW/WWF war mentioned above (with Extreme Championship Wrestling also providing competition by the mid-90s).

However, with multiple nationwide promotions fighting for dominance and the illusion of kayfabe long gone, it’s no surprise that intellectual property issues became much more important. After all, if wrestlers controlled their name and brand, they could easily defect to another organization and take it with them without penalty. Likewise, if the promoter controlled all of the assets, the wrestler could leave but they’d be of much less value to a competitor.

This was a trend that would take off during the 90s, as the competition between the promotions was heating up, and would carry on to even today.

However, to understand what’s going on, we first need to step back and understand how copyright and trademark impact professional wrestling.

How Trademark and Copyright Affect Wrestling

When it comes to the business of professional wrestling, both copyright and trademark play very important roles. Promotions hold and exploit the copyright in the shows that they put on. When you watch a wrestling show on television, buy a DVD or view something on a streaming platform, that’s the promotion using their copyright.

Likewise, the promotion also holds a trademark in its name, logo, slogan and other elements used to identify it as a business. All of this is fairly standard.

Where things get more thorny is when looking at the wrestlers and their gimmicks. Here, copyright starts to take a backseat. Though it is possible to copyright a fictional character, and thus theoretically possible to copyright a wrestling character, characters in wrestling change regularly and generally don’t have much that would likely be seen as protectable.

However, these wrestlers have names and nicknames. Mark Calloway is not nearly as well known as The Undertaker, which is a trademark that the WWF/E filed in 1993. According to the United States Patent and Trademark Office, that’s just one of more than 2,000 trademarks that the WWE currently holds (many of them obtained through their purchase of competitors).

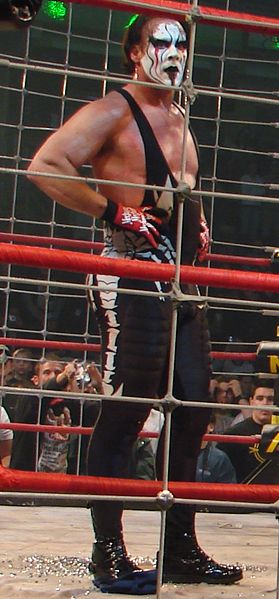

But this isn’t to say that savvy wrestlers haven’t gotten in on it as well. In 1995, professional wrestler Steve Borden registered his much-more-famous moniker Sting. In more recent times, such trademark registrations are used by wrestlers ahead of a potential move such as when wrestler Jonathan David Good filed a registration for the name Jon Moxley before making the jump from WWE to All Elite Wrestling (AEW). Good had used the name in other promotions before signing with WWE.

And that, in turn, is one of the WWE’s ways of controlling their branding. Though performers often come to them with established names and characters, they are usually given a new name shortly after arrival.

For example, for most of Fergal Devitt’s career, he was known mostly as Prince Devitt. However, when he made the move to join the WWE in 2014, they renamed him Finn Balor. It should be no surprise no one that the WWE registered a trademark on that name at the same time.

For WWE, this makes sense. It makes it so that wrestlers and performers can’t simply leave and take the value that WWE helped put into them. However, for the performers, it means that they can work for years on a character, gimmick and persona only to have much of it vanish after they leave.

However, this isn’t to say that WWE has always been the victor of its trademark battles. In 1994, the then-WWF entered into an agreement with the World Wildlife Fund (Also WWF) where the wrestling promotion agreed to minimize the use of its initialism both in print and on TV.

It did not and, in 2000, the charity sued for violations of that agreement. In 2002, the company began making the transition to its WWE moniker, which stands for World Wrestling Entertainment.

It was, perhaps, the single biggest example of trademark law changing the wrestling world.

Still, it’s far from the only one. Whether it’s Matt Hardy fighting to keep control of his “Broken” gimmick after he left Impact Wrestling or Joan Laurer changing her legal name to Chyna so she can use her identity post-WWE, trademark has been a guiding hand in wrestling for decades.

That’s not something that’s likely to change, especially as wrestlers and promoters alike strive to maximize control over their work.

Bottom Line

What makes intellectual property in wrestling so interesting is not that it raises any unique or interesting legal questions, but in how it is used. Trademark isn’t just a tool for warring promoters, but a tool used by promoters and talent to try and get a leg up on one another.

These intellectual property tussles have had serious consequences in the ring with plots being changed, wrestlers being renamed and gimmicks altered to avoid conflict.

Professional wrestling is a rare environment where you can actually watch the fallout of intellectual property issues impact what is being shown on screen in real-time.

To that end, it’s an interesting thought exercise and a unique world to explore.

However, these issues aren’t going away in time soon. With rise of AEW and the growth of independent promotions, the tension is getting high again and we’re entering an environment that more closely resembles the one in the 90s than the past two decades.

It will be interesting to see what roles IP plays as the new wrestling wars heat up.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.