Copyright, Royalties and Christmas Music

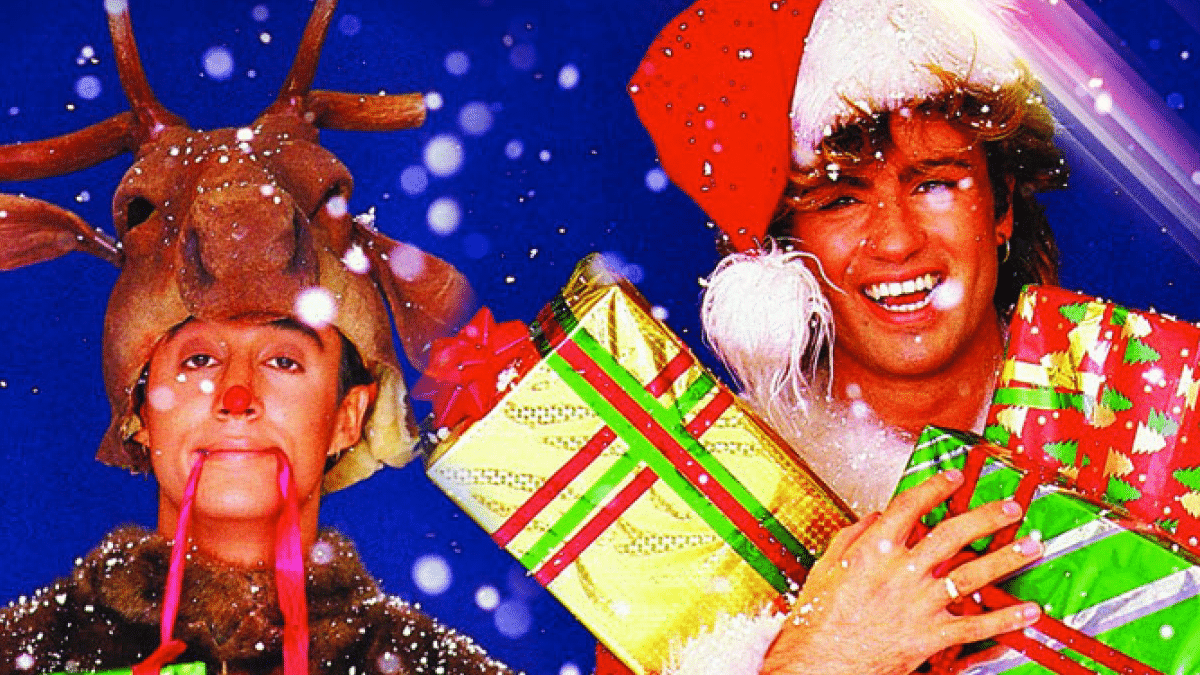

Last Christmas? How about EVERY Christmas...

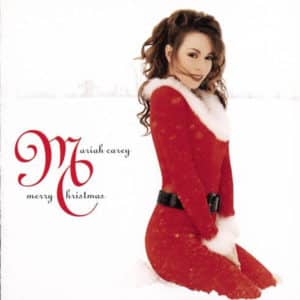

For the first time since its release in 1994, Mariah Carey’s song All I Want for Christmas is You has hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.

If that seems odd that a 25-year-old song would, for the first time ever, top the charts, it shouldn’t. Christmas music is in a very different category than most pop music, which tends to rise and fade in popularity quickly. Christmas music is cyclical, with established favorites coming back year after year after year.

In the case of All I Want for Christmas is You, the song has charted every year since it’s release. It even peaked at No. 3 last year and No. 9 the year before. This also establishes it as the song that has taken the longest time to reach No. 1 and the song has helped her cement other records including the longest cumulative time at No. 1.

For Carey, this has been very lucrative, having earned her an estimated $60 million in royalties through the song’s run.

The long-term and repeated success of All I Want for Christmas is You highlights a simple truth: Christmas music is big business. Artists work every year to create new Christmas staples and, though nearly all fail, those that do can expect to reap rewards and royalties for a long, long time to come.

Comedians have even parodied this idea. In 1959 Tom Lehrer released the album An Evening Wasted with Tom Lehrer, which included the song A Christmas Carol, his comedic attempt at producing such a Christmas staple. More recently, in 2007, Stephen Colbert released Another Christmas Song, his spoof on the genre.

But who is making all of the money from these modern Christmas classics and where did this tradition start? To get the answers we have to study a little history and a little copyright law…

The History of the Christmas Hit

As with a lot of things, it’s difficult to pick exactly when this trend started. Music has always been a big part of holiday traditions for as long as such traditions have existed. As long as there has been Christmas music, there have been Christmas songs and people writing them.

One of the first examples of a modern Christmas staple is the 1934 song Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town. Written by John Frederick Coots and Haven Gillespie. It was an instant hit, despite coming out in the middle of the Great Depression, and gets plenty of airplay today in the form of over 200 covers.

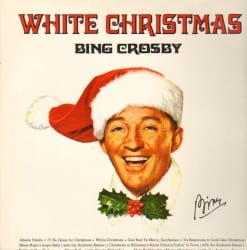

However, the more modern tradition of a song written for the season that becomes lucrative after it returns year after year likely saw its start in the early 1940s . As we discussed back in 2011, both Little Drummer Boy (written by Katherine K. Davis and performed by the Trapp Famly Singers) and White Christmas (written by Irving Berlin and performed by Bing Crosby) were created around that time.

However, with all of these songs, there wasn’t much of an attempt to make a Christmas staple. White Christmas was written for the movie Holiday Inn, a film about all of the holidays, and Little Drummer Boy was based on a Czech carol and not released until 1951.

Still, staples they became. Little Drummer Boy hit No. 1 on the Billboard charts in 2013 thanks to a Penatonix cover and White Christmas has become the best-selling single ever, with over 50 million copies sold.

Toward the end of the decade, writing of commercially-successful Christmas songs became more common. In 1949, Johnny Marks wrote the Gene Autry-performed song Rudolf, the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Based on a popular book from a decade earlier, the song became an instant success and found an immediate place in Christmas playlists.

The very next year songwriters Jack Nelson and Steve Rollins saw the success of Rudolf and created Frosty the Snowman, which charted in 1950 and itself became an instant staple. It was also first recorded by Gene Autry (though a Jimmy Durante version was released the same year).

That tradition continued into the 1950s with songs like Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree (written by Johnny Marks and first recorded by Brenda Lee), Jingle Bell Rock (written by Joseph Carleton Beal and James Ross Boothe and first recorded by Bobby Helms) and even The Chipmunk Song (written by Ross Bagdasarian Sr. as David Seville and performed by The Chipmunks). All of those songs were written in the late 50s and all have become cornerstones of the holiday.

Even Elvis Presley got in on the act. In 1957 he released his cover of the 1948 song Blue Christmas by Ernest Tubbs. Other songs from the 50s include I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus, Run Run Rudolf, It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas and There No Place Like Home for the Holidays. The 50s, without a doubt, were the peak time for what we now consider “Christmas classics.”

One thing that’s important to note is that, with all of these songs, they were released as pop or novelty songs. Though the authors had certainly hoped to release a Christmas staple, all of them were released as pop songs at the time. This view as a Christmas staple is something that comes from hindsight.

That hindsight makes it more difficult to determine what is and is not one with regards to more recent music. In addition to All I Want for Christmas is You, Wham!’s Last Christmas (don’t worry Whammegeddon players I’m not playing it), Santa Tell Me by Ariana Grande and, yes, Mariah Carey’s Oh Santa! are all more modern songs that may or may not become staples with time.

In fact, what’s unusual about Carey’s All I Want for Christmas is You is that it was neither a staple immediately nor did it take 50 years to be seen clearly as one. When looking at other tracks, it was both incredibly slow and incredibly fast on its way to becoming a Christmas No. 1.

Still, with all of this recurring success, there’s certainly at least some money to be made. The question is: Who is making it?

So Where is the Money Going?

One thing to note is that every single song listed above is still protected by copyright, both in its composition and its recording. January 1, 2020 will see works from 1924 fall into the public domain, meaning that all of those songs have decades more of copyright protection.

What this means is that every stream, purchase, download, radio play, etc. is making someone money. The question of who, however, gets more complicated.

I discussed this in MUCH greater detail in my 2017 post on music licensing and music copyright. However, for our purpose today, the main thing is that there are two copyrights for each song: The composition and the recording. The composition, or publishing right, is the lyrics, the notes and anything else that can be written down. The recording, or master, is simply what you listen to, it’s what the musicians create based off of the composition.

Who gets paid what depends heavily on the specific use. For example, in the United States, only the composer (or their publisher) is paid when a song is played on the radio. That’s because radio airplay is considered a public performance and there is no public performance right the recording artist. The same holds true for music played in restaurants, stores, bars, etc.

As such, every time you hear a song in a store or on the radio, it’s the songwriter/composer, not the performer, that’s getting the royalties. For Mariah Carey with All I Want for Christmas is You, this is not a major obstacle as she is listed as one of the song’s writers. However, many musicians don’t perform the songs they write and miss out on these royalties. Examples of that can be found above with many of the 40s and 50s Christmas staples.

Still, most uses of a song require a license (and a royalty) for both the composition and the performance. This includes digital streaming, use in movies (unless they use a cover version), purchased copies, etc. require a license from both.

It’s worth noting that many of the recordings discussed above were released before February 15, 1972. This means that they are considered pre-1972 sound recordings and are technically not under federal purview. However, the Music Modernization Act placed such songs under a similar licensing regime to ones created after it, narrowing the differences.

Overall, music licensing is very complicated but it’s worth noting that the performer you’re listening to may not be earning any royalties from the work depending on how you’re hearing it.

The most lucrative Christmas songs for the performer are the ones where they are also a writer. This is a big part of why Carey has made so much from All I Want for Christmas is You and other musicians are trying to do the same thing.

Bottom Line

In the end, Christmas songs are big business. There’s no doubt about it. If you can write a song that becomes a Christmas staple, you can likely live off those royalties for the rest of your life. It’s a stable, recurring revenue stream.

However, it’s a bit like winning the lottery in terms of the odds. Even great bands and talents with success elsewhere have struggled to make a Christmas song that returns year after year. Some find pop success one year but watch it fade into obscurity the next.

There’s no science to it. In many ways, it’s one of the first attempts at artists to “go viral”.

Still, the temptation will always be there. For artists, the thought of having a Christmas classic to their name is simply too sweet. Who wouldn’t want that kind of security?

So, expect artists to keep trying and most to keep failing. Christmas songs may be timeless but Christmas tastes are also fickle. That which becomes a hit one year probably won’t the next. Still, that won’t stop artists, songwriters, producers and others in the music business from trying to predict the trends that lie ahead.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.