Revisiting Don’t Download This Song by Weird Al

Taking a look back at Weird Al's piracy PSA spoof...

The early-to-mid 2000s were a strange time for copyright in the United States. Napster had been launched in June 1999 and, though it only survived until July 2001, it forever changed the piracy landscape.

After its closure, the void left behind was quickly filled by a variety of file sharing services. Apps such as LimeWire and KaZaA stepped into the gap and new technologies such as BitTorrent and not only provided a more-difficult to shutter infrastructure, but also expanded capabilities. Where Napster was limited to music files, these services could trade any type of content.

Rightsholders responded to this in a myriad of ways. However, one of the most heavily-publicized and controversial was when, in 2003, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) began targeting individual file sharers for litigation. The actual impact of the campaign, which lasted for five years and saw some 30,000 lawsuits, is still hotly debated but it did make for interesting conversation and comedy.

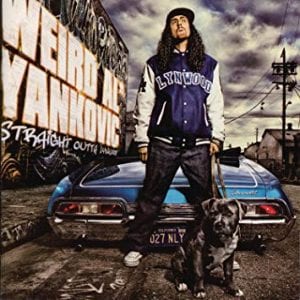

One of those to take a jab at the campaign, and overall piracy climate of the time, was the parody master “Weird Al” Yankovic. In August 2006, he released the album Straight Outta Lynwood, which featured the song Don’t Download This Song.

Now, more than 13 years later, we’re going to take a look back at it and see how well the song holds up and whether it’s a relic of a time gone by or if it is still relevant today.

Weird Al’s History with File Sharing

As an artist who was popular before the rise of Napster and has remained as such ever since, Weird Al was definitely impacted by the rise of file sharing and subsequent changes to the music industry.

However, he’s largely kept his personal views on file sharing out of the spotlight, using his trademark humor to deflect any questions. For example, in a May 2000 fan Q&A, he was asked about Napster and responded:

I have very mixed feelings about it. On one hand, I’m concerned that the rampant downloading of my copyright-protected material over the Internet is severely eating into my album sales and having a decidedly adverse effect on my career. On the other hand, I can get all the Metallica songs I want for FREE! WOW!!!!!

For Al, the bigger problem with file sharing wasn’t necessarily lost revenue, but rather, mistaken identity. Since Napster and other file sharing services at the time relied on users to identify songs, many parodies were attributed to him that were not his.

This was frustrating for two reasons. First, many fans were worried that they had missed one or more of his CDs. Second, many of the songs attributed to him were extremely vulgar or otherwise contained material that went against his image.

Still, at a time where musicians were taking sides on file sharing, Al largely stayed on the sidelines. That is, until August 2006 when he released Straight Outta Lynwood and the track Don’t Download This Song.

Don’t Download This Song

Don’t Download This Song is not a parody of an individual song, but rather, is a style parody of charity songs, which were very popular in 80s. This included tracks such as We Are the World and Hands Across America.

We Are the World was directly parodied by Camp Chaos in 2000 with the song Sue All the World, which was also about the fight against file sharing (specifically Napster).

The easiest way to break down this song is to look at it verse by verse, which is how we’re going to do it.

The first verse is a parody of many of the anti-piracy PSAs that were common at the time. It tells the listener that they may be tempted to download MP3s illegally but, if they do, the shame “will leave a permanent scar” and, if you continue:

‘Cause you start out stealing songs, and then you’re robbing liquor stores

And selling crack and running over school kids with your car

Tonally, the verse is a great parody of those PSAs, which were often extremely heavy-handed in their approach. Interestingly though the four services that are listed in the verse, Morpheus, Grokster, LimeWire and KaZaA, are all long gone (at least in the incarnation they were around in 2006). Not only were they shuttered through legal action, but that style of file sharing has dwindled.

It’s also worth noting that the verse makes reference to “international copyright law” even though no such thing exists. Copyright law is national in scope though there are countless treaties that attempt to harmonize it more or less globally.

The second verse is much shorter and is a warning against messing with the “R I double A”.

They’ll sue you if you burn that CD-R

It doesn’t matter if you’re a grandma or a 7-year-old girl

Obviously CD-Rs have since fallen completely out of favor for music (or any) piracy. If anything, they were already waning in popularity in 2006.

Nonetheless, the lines about suing a grandmother and a seven-year-old girl ring true to those who remember those years. The first is a likely reference to Gertrude Walton, who was sued in February 2005 months after her death. The young girl is likely a reference to Kylee Anderson, whose mother was sued that same year. Though Anderson was ten at the time, she was seven when the alleged infringement too place.

Though both cases were quickly dropped, the headlines and the publicity generated by these cases likely played a role in the RIAA backing off this strategy just a few years later.

The third and final verse is the probably the most problematic. It makes the argument that file sharing doesn’t hurt anyone other than wealthy artists.

Don’t take away money from artists just like me

How else can I afford another solid gold Humvee?

And diamond-studded swimming pools, these things don’t grow on trees

This argument was actually very common during this time (and is still common today). It is punctuated by the fact that many of the artists that were the most vocal about file sharing were also some of the most successful and wealthy including Metallica, Madonna, Dr. Dre and Elton John to name a few.

However, the past decade has not been kind to that perception. First, it’s become clear that file sharing (and the industry shifts it helped created) harmed musicians at all levels. In 2012, there were an estimated 45% fewer musicians working than in 2002. Second, though streaming has led to a rebound in the music industry, it’s still barely half what it was in its 1999 peak.

While it’s true that those who initially led the charge against file sharing were not sympathetic, they weren’t the ones hurt the most. After all, every musician named in Don’t Download This Song and featured in Sue All the World are still at least somewhat big names.

The chorus of the song, which is also used for the outro, tells the listener to “Go and buy the CD, like you know that you should.” It’s interesting in hindsight because the iTunes store launched in April 2003. By the time the song was released, there were legal ways to purchase digital tracks.

However, CD sales, though already struggling, would nosedive starting in July 2017 when Spotify would launch in the US and kick off the streaming revolution here. Album sales have been sinking to new lows ever since.

It seems, for most music listeners, the record store is not where they belong. It’s on (legal) streaming services. In fact, vinyl sales are on track to earn more than CDs this year.

How Well Does it Hold Up?

Comedy is often one of the quickest types of entertainment to age. Comedy about technology is guaranteed to age even faster. Though most of Weird Al’s music seems pretty timeless, this song feels dated just 13 years after its release.

When it comes to music piracy, BitTorrent and file sharing services have been replaced by stream rippers (after originally being replaced by cyberlockers). When it comes to legal music, CDs have been replaced by streaming services (after originally being replaced by digital purchases).

However, it’s pretty easy to point out how technology and internet culture have moved forward in 13 years. The song was never going to hold up in that regard. That was never the goal.

The goal, instead, was to lampoon the heavy-handed tactics used by the RIAA and others during that time period. It did so by parodying both the style of music commonly for PSAs around that time and much of the language.

With that in mind, it was very spot on.

Though I consider myself a strong supporter of creators’ rights, the tactics and approach of the RIAA did little to help the situation. It did nothing to discourage piracy, it turned public opinion against musicians and it hurt the credibility of the RIAA as an organization.

That makes it good that the RIAA has learned from its mistakes. It, like most organizations, focus not on targeting end users (either with litigation or marketing) but on targeting those operating pirate sites and services. The meme-worthy Piracy, It’s a Crime PSA is from 2005, Don’t Copy That Floppy 2, which was by the software industry, is from 2009. The past decade has seen very little in terms of a direct-to-consumer campaigns (legal or otherwise), by the RIAA or anyone else.

To that end, Don’t Download This Song may be a small part of the reason. The RIAA’s message was being openly mocked from within the industry it represents. It’s hard to get more significant bad press than that.

So, while the song doesn’t hold up, it’s not because it wasn’t a great biting commentary of the time it was written, it’s because the world around it changed. The approach the song is lampooning has been dead for a decade and, though it’s far from forgotten, it’s a rapidly-fading memory.

It’s a beautiful time capsule of a very strange time and one that, thankfully, has changed a great deal.

Bottom Line

One interesting thing about the song is that we still don’t know where Weird Al actually sits on the issue of file sharing and piracy. Though he makes it pretty clear that he’s opposed to the RIAA’s tactics from this era, that’s not the same as being pro-piracy.

However, this shouldn’t be a shock. Weird Al has worked to keep his politics and personal beliefs out of his music as much as possible. His goal with this song was to parody what was a cultural touchstone at the time, even if not all of his fans saw it as such.

Going back to his fan Q&As, in a September 2006 one, a fan asked:

Hey Al! Love your work, but aren’t you slipping a bit? “Don’t Download This Song?” I mean, the whole downloading music from the Internet controversy is like 5 years old, man!

To which Al responded:

Yeah, you’re absolutely right. It’s a completely dead issue – people stopped illegally downloading songs off the Internet years ago, and the RIAA is no longer taking legal action against P2P sites or criminalizing people who share files. What was I thinking? Thanks for setting me straight. By the way, don’t forget to e-mail Neil Young and ask him why he’s still writing songs about Iraq on his new album. I mean, come on… that war is so 2003!

Al was right, the song was definitely relevant in 2006, even if it was past the peak of the controversy. Today though, it’s a clear product of its time, a representation of a crazy time period that is now more than decade old.

The universe has changed but this song stands as a reminder of a recently-bygone era. It may not be as timeless as many of Weird Al’s songs, but it may go down as being one of the most important, maybe not for the music, but for the change it likely helped bring.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.