The logic is simple: If you don’t want others to use your image without permission, place your watermark over it. That way it can’t be used in a professional capacity and any other sharing at least carries your name with it.

It’s something that’s easy to do, with multiple free tools available. It’s also a step that, if done well, can make it nearly impossible to get a clean version of the image without getting it from the creator.

However, the popular technique has been showing some cracks over the years. As image editing software has evolved, removing low-security watermarks has become much easier.

But now Google researchers may have exposed an even larger weakness. They’ve developed an algorithm that can remove watermarks from images en masse. It works cleanly, effectively and quickly.

However, before you panic, take a moment to understand the limitations of this new approach and the very simple ways it can be defeated.

Understanding the Algorithm

To date, most work on removing watermarks from images have focused on ways to quickly remove it from a single image using fairly standard image editing techniques. Though the software has improved some, the process is typically either tedious or imperfect.

To date, most work on removing watermarks from images have focused on ways to quickly remove it from a single image using fairly standard image editing techniques. Though the software has improved some, the process is typically either tedious or imperfect.

In short, getting good results has always required either a lot of work or a lot of luck.

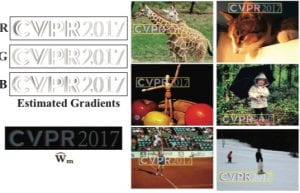

But the Google Research team (Tali Dekel, Michael Rubinstein, Ce Liu and William T. Freeman) took a different approach. In their paper, the team took hundreds of images with the same watermark and ran them through the algorithm.

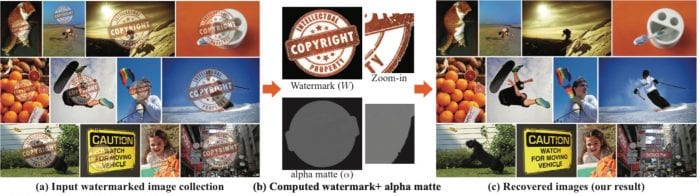

While humans can easily distinguish between watermarks and images, computers can’t. The researchers got around this problem by having the computer learn what the watermark is by examining the hundreds of images and detecting the common elements from them. Then the researchers simply created a matte based upon that watermark that was removed.

The approach was extremely successful. The researchers were able to remove the watermark effectively and quickly from hundreds of images. For example, the team was able to remove the watermarks from 422 AdobeStock images in just over 33 minutes with nearly all of the time for the “pipelining”, which is the watermark detection.

That is far faster than it would have likely been to remove it from just a couple of images by hand.

The process wasn’t perfect, some of the images still showed artifacts (especially when the the watermark was complex and the background smooth) but the success rate was extremely high.

But while this research opens up an obvious new battlefront in watermarking, it’s not necessarily an attack to worry about today and it’s something that can be easily avoided tomorrow.

Limitations of the Approach

If you’re looking to use this approach to remove watermarks (or looking for a way to defeat it) it has two severe limitations to be aware of:

If you’re looking to use this approach to remove watermarks (or looking for a way to defeat it) it has two severe limitations to be aware of:

- It Requires A Large Number of Images: The researchers used a subset of 50 images to do watermark detection. Much smaller number and the computer can’t learn to separate the watermark from the rest of the image.

- The Watermarks Must Be Identical: Though the watermarks can be in different places on the image, any variation in the mark will throw off the learning and the removal.

The first really limits how this attack can and will likely be used. This is a process designed for removing watermarks from large collections of photos, not individual images. Though the automated parts of the process don’t take a great deal of time, obtaining and downloading enough images would be a time sink of its own.

This approach is only practical on collections larger than 50 images and, from a time standpoint, probably needs much more. If you don’t have a large collection or there isn’t much interest in capturing the whole collection, this approach is not an ideal attack.

The second limitation, however, is the important one, it’s what spells out how to defeat this tactic and what artists and stock photo sites alike need to do moving forward.

How to Beat It

While the news of an algorithm that defeats visible watermarks is never good news for artists, the story does have a silver lining: The system is easily defeated and, in the long run, may make watermarks better.

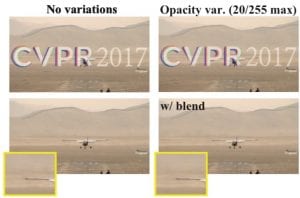

The system only works if the watermarks are identical. This means that any change or randomization in the watermark will fool the system.

To be clear, it’s not enough to simply move the watermark around the image. As long as it’s the same size and style, the system will detect it. However, altering the watermark from image to image breaks the system.

For example, the researchers didn’t even attempt the algorithm on Getty Images’ new watermark. The watermark not only occupies more real estate on the images, but also has the photographers name and a unique number for the image.

This mark, because of its uniqueness to the image, remains fairly secure (setting aside browser-based attacks that let you access lower-resolution images). It can’t be removed trivially either by single-image attacks or algorithm-based attacks such as this.

AdobeStock, Fotolia and other sites that they did test with, however, should be concerned. For them, and for other artists and sites with vulnerable watermarks, now is the time to upgrade your watermarking method.

Basically, follow in Getty’s example and make sure that every image has a unique watermark. Likewise, remember that the less transparent the watermark, the more secure it is as well (though an opaque one is no guarantee of security as we learned in earlier testing).

Also, looking at the time required for removal, the larger the watermark the more difficult it was for the system to function. Where Fotolia’s 199×66 watermark only took 5 minutes to pipeline with 50 images, 123RF’s 650×433 mark took 115 minutes for the same number of images.

This upgrade will make your watermarks more secure against all types of attacks and more useful to viewers. Some information to consider adding includes:

- Name of piece

- Product number

- URL to Find Original Image (Shortened Hopefully)

- Date Image Was Created/Uploaded

- Collection Name

In short, find information that is unique to that image (or only to a small subset of images) and is useful to the user. Then, add that information to the watermarks. Most watermarking applications have this ability but it’s rarely used because it’s seen as not necessary.

However, the necessity of such a step is exactly what this research has changed.

Bottom Line

Even with this paper published this attack is not something to worry about today or tomorrow. Though the researchers published the equations they used, they didn’t release the exact software.

While this proof of concept will certainly speed up the generation of such software, there’s still time to go through and upgrade your watermarks in response to this. This is not what we would think of as a zero-day exploit.

Yes, it’s a major pain to have to redo hundreds, thousands or even millions of watermarks and it may not be worthwhile for many creators, especially if they aren’t in particular danger of this attack.

But, if your business relies on the strength of your watermark, the time to start upgrading is today because tomorrow could be too late.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.