Flickr and Facebook STILL Strip EXIF Data

In November 2008 I wrote an article that highlighted how Flickr and Facebook both strip out EXIF data in images that are uploaded. A comment to that post recently got me excited about the possibility Flickr had changed its ways and initial testing indicated it might have.

However, sadly, a year and a half later, nothing has changed. I’ve redone the tests with no luck. Flickr and Facebook are both stripping out EXIF data to uploaded images. The only exception is that I can now confirm Flickr is preserving the data on original images, just not on the automatically generated resized versions.

Below is a quick analysis of the problem and why it is a serious issue that every photographer should be worried about.

How Flickr Does It

If you upload images to Flickr, the site automatically generates up to five different versions including square, thumbnail, small, medium and large. If you are a non-pro account user, these are the only images sizes available as they can not download originals.

![]()

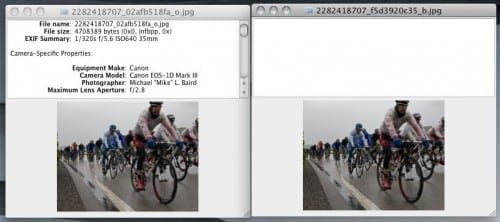

The original files preserve the EXIF data but the other sizes, the ones generated by Flickr. Do not. For example, compare the EXIF data stored in the two sizes of this image, the original being on the left. (Note: Original image by mikebaird and licensed under a Creative Commons License)

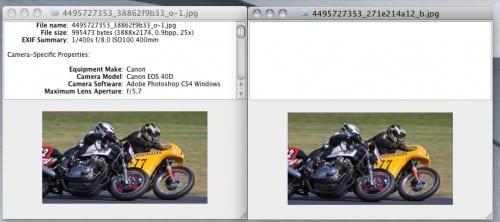

Since that image was from 2008, I redid the test using this image, which was uploaded this month and found the same results. (Note: Original image by dicktay2000 and licensed under a Creative Commons License)

In short, Flickr still has the same problem it did two years ago and is stripping out the metadata on images when it resizes them. Unfortunately, it resizes all images uploaded and, in the case of unpaid users, there is no way to access the originals. Furthermore, since the original images are usually too large for Web use, it is the smaller ones that get passed around the most.

Facebook Too

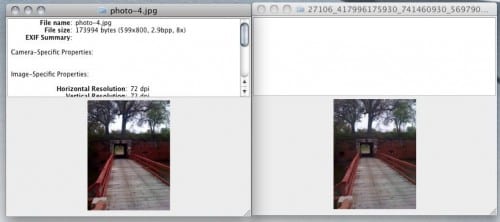

I also repeated the test with Facebook, using an image I took during a recent geocaching run, and compared an original from my phone to the version I downloaded from Facebook. The original is on the left.

Unfortunately, with Facebook, there is no way to download the original photo and, as such, the EXIF data is never seen publicly. All you can do is either add a visual watermark or hope that, if the image is passed around on the Web, that attribution remains intact.

Why This is Bad

With the recent near-miss in the Digital Economy Bill in Britain over orphan works, it is clear that orphan works legislation will be a part of the future of copyright.

Though there were differences between the UK bill and the two that were tried in the U.S. without success, the crux is the same. If the owner or the rightsholder of a copyrighted work can not be found or identified, the work can be used so long as the person using it performed a reasonable search.

This issue most directly impacts photographers and visual artists as their work is more difficult to search for and often has no attribution affixed to it. As such, image sharing sites, such as Flickr, should be doing everything they can to help identify the authors of the works they host, including preserving the EXIF data.

The failure to do so, especially for Flickr, which caters so strongly to professional photographers, is very dangerous and may create serious problems down the road for the users who trusted the service.

Bottom Line

While I grant that this is an invisible problem in that EXIF data is not immediately seen by those who view or use the site, it is an important one to fix. Hopefully both of these sites will work on a fix to preserve the metadata of images uploaded to them to prevent creating orphan works.

After all, the problem of orphaned works is not one that’s going to go away and the only way it can be resolved with current works is through cooperation of all involved and that includes photo sharing sites.

In the meantime though, just be aware that, when you upload your images to Flickr or Facebook, your metadata may not travel with them.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.