The Birth, Death and Legacy of Alan Smithee

Most of the time, giving credit is seen as the right thing to do. Most creators want credit for their work and, on the whole, people are happy to give it or at least feel/have an obligation to do so.

But what happens when creators don’t want credit for their work, at least not directly?

For authors, this is simple. They publish under a pseudonym or a pen name.

Many times, pen names are more about marketing than refusing credit. Many of the most famous authors in history used pen names, including Mark Twain, Lewis Caroll, Dr. Seuss, Anne Rice and Voltaire to name a few.

However, sometimes authors really don’t want to be connected with a work. They may fear reprisal, may not want the work connected with their other writing, or simply want to avoid the spotlight. In those cases, authors can publish anonymously.

But things get much more complicated in the film industry. There, unions and trade groups have strict rules about who should be credited, what credit they should receive and how that credit should be presented.

One such trade group, the Directors Guild of America (DGA), which has strict rules barring directors from using pseudonyms. The goal of that policy was to avoid any directors being forced to use one by studios and ensure that all directors are properly credited for their work.

However, in 1969 that policy ran into a serious problem when two directors wanted to remove their names from a film, only to find out that they couldn’t do so.

The Birth of Alan Smithee

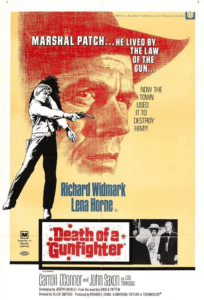

In 1969, the film Death of a Gunfighter was a deeply troubled production. Lead actor Richard Widmark was at odds with director Robert Totten and arranged to have him replaced mid-shoot by Don Siegel.

However, when the film was finished, Siegel didn’t want credit for the film. He felt that the final product was not his creative vision and claimed that Widmark was the one that was actually in charge. After Totten also refused to take credit for the film on the same grounds, the DGA came up with a simple solution: Create a fictional director.

Initially, they chose the name “Al Smith” but felt that it was too common and were also worried that other working directors shared the last name. They then changed it to “Allen Smithee”, which was the name that appeared in the film’s credits.

When the name first debuted, reviewers and others didn’t realize that it was a pseudonym. Critic Roger Ebert famously said, “Director Allen Smithee*, a name I’m not familiar with, allows his story to unfold naturally.”

That review now carries an editor’s note that reads, “It was not until years after this review was written that ‘Allen Smithee’ became publicly known as a pseudonym used by directors who wanted their name removed from a film’s credits.”

However, the name stuck. Though it would eventually change to “Alan Smithee”, the name lasted over three decades as the only DGA-approved pseudonym that directors could use.

During that time, the name would appear as the director in dozens of films. However, perhaps the most famous use of it on Twilight Zone: The Movie. There, the first segment’s second assistant director, Anderson House, opted to use the name following a tragic helicopter accident during filming that ended the life of actor Vic Morrow and two children.

Though such a use of “Alan Smithee” for an assistant director credit was unusual, the name would go on to be used in a variety of media including TV, video games and comic books.

This helped to grow the cultural relevance of Alan Smithee and that, ultimately, is what led to his abrupt retirement.

The Death and Legacy of Alan Smithee

In 1997, director Arthur Hiller released the mockumentary An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn. It featured the story of a director named Alan Smithee, played by Eric Idle, who wanted his name removed from a film but the only name he could change it to was his own.

The film performed terribly and was both a financial and critical flop. To make matters worse, Hiller wanted his name removed from the film, meaning that the director of the film is listed as “Alan Smithee”.

The negative publicity around the film along with self-referential credit pushed the DGA into doing away with the pseudonym. Now, directors who want their names removed from films have their new names chosen on a case-by-case basis.

The first example of this was the 2000 film Supernova, where director Walter Hill was credited as “Thomas Lee”.

However, the name does live on in some respects. First is its notoriety, which persists even today. It’s known well as the hallmark of a bad film, meaning that it was so bad the director wanted their name removed from it.

But it also lives on in (more limited) use. The Alan Smithee IMDB entry lists dozens of credits to the name, including 15 credits since 2020. However, it’s safe to assume that those projects were not completed under DGA rules.

That aside, it’s clear that the career of Alan Smithee is far from over, even if the DGA tried to force him into retirement.

Bottom Line

One thing the Alan Smithee name didn’t do was help keep directors anonymous. Take a brief look at the Wikipedia page for the name, and you’ll quickly find that every almost every director who used the name is known. There are only a couple of cases where the director is still unknown.

But that really wasn’t the point. While Alan Smithee is a credit, or rather a non-credit, for directors, it was meant more as a protest than a way to remain anonymous.

Alan Smithee was a way for a director to indicate to the public that they did not want to be connected with the work. Whether it was due to creative differences, a perceived lack of quality or some other controversy, it was a way for a director to distance themselves from the final product.

So, while the name of Alan Smithee is one of the most interesting tales when it comes to attribution, it really isn’t about attribution at all. It’s about sending a message to the audience that basically says, “Don’t blame me for this.”

In that respect, the name very much lives on…

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.