New Guidelines to Help Tackle Self-Plagiarism in Research

Self-Plagiarism is one of the most complex and hotly debated topics in all the discussions about plagiarism. However, it all comes down to a simple question, “When, if ever, is it acceptable to reuse your previous words when producing something new?”

Much of the ethics and legality of self-plagiarism will depend on the nature of the writing and the audience it is for. A lawyer, for example, will be held to different standards than a fiction novelist or a journalist. However, even within specific fields, there are often debates about when and how it is acceptable to reuse one’s previous work.

Nowhere has that issue been more complicated than scientific publishing. There, editors and researchers alike have struggled with the ethical and legal boundaries of recycling text. This has often resulted in researchers contorting their writing in a bid to find new ways to describe a process they’ve done before, or editors rejecting papers simply due to overlapping text.

Most frustrating has been the lack of overall guidance on this topic. It’s left many unsure of how to handle this issue.

However, one academic, along with his colleagues, is hoping to change that. Cary Moskovitz of Duke University recently published a series of guidelines and resources dedicated to addressing text recycling, looking at it both from the perspective of a researcher and an editor.

What he’s produced is one of the most comprehensive and nuanced looks at the issue. It understands both text recycling is both ethical and important, but also the dangers of duplicative publication.

How it Came About

According to an interview Moskovitz gave in Science Magazine, the idea for the resources came after he sought out guidance for his students on the issue but found very little. According to Moskovitz, the majority of the resources he found on the topic were directed at editors, not researchers, and he sought to fill that void.

To achieve that, he created the Text Recycling Research Project (TRRP), which both aims to study the issue and also provide resources and guidance on the subject.

To that end, he’s found that modest recycling is almost ubiquitous in the field of research, with articles having an average of three sentences copied either in part or whole. However, in a survey of editors, he also found that editors routinely asked authors to rephrase portions of their work to avoid both potential ethical and legal issues.

Of particular concern was copyright infringement. Since many journals require authors to sign over their rights in published papers, editors were concerned that recycled language from a previously published paper could pose a copyright issue.

To address all of this, Moskovitz and others at the TRRP sought out advice from publishers and others in the field to create a set of workable guidelines. To that end, they realized there was a need for nuance in this subject, and that is something that came through in their resources.

What the Guidelines Say

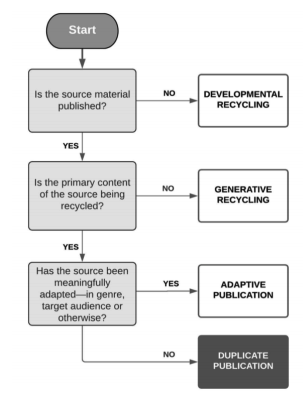

The main crux of the guidelines is to stop thinking of text recycling or self-plagiarism as a monolithic thing. Instead, the TRRP actually identifies four different kinds of recycling that researchers may run into:

- Developmental Recycling: This is the reuse of material from unpublished documents. According to TRRP, this is common and generally considered acceptable. An example here would be reusing language from a talk at a conference in a published paper.

- Generative Recycling: This involves using the text from a previously published source in a source that expands upon the previous work or is otherwise making a different contribution. For example, this might include reusing portions of the method of an experiment when performing a similar, but different one at a later date.

- Adaptive Publication: This involves taking portions of a previously published work and adapting it to a different audience. An example would be taking a published research paper and adapting it for a textbook or a news article.

- Duplicative Publication: This is simply taking previously published work and republishing it to the same or similar audience. The common example here is publishing a research paper in two separate journals without proper notice.

The four types of recycling are in order from least worrisome to most worrisome. This means that, while Developmental Recycling is generally acceptable, Duplicative Publication rarely is. As for both Generative Recycling and Adaptive Publication, it’s the details of how the republication is done that makes the difference.

In those more borderline cases, the TRRP guidelines put the emphasis on transparency with both editors and readers. This echoes what we were talking about on this site in 2011 on these issues.

Ultimately, the TRRP guidelines add a relatively simple idea to the discourse around self-plagiarism, but it’s one that adds many layers of much-needed nuance. Yes, there are dangers to self-duplication, but there are also times and places where it is necessary, and rephrasing just for the sake of rephrasing is a disservice to the reader.

The TRRP balances those concerns nicely and strives to bring nuance back to the conversation on text recycling and self-plagiarism. That can only be a good thing.

Bottom Line

The biggest limitation of these new standards is that they won’t be seen as a standard, at least not immediately. Though the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) aided the TRRP in its work, there’s no real force behind. Publishers and editors will continue to take diverging approaches on this issue.

However, it provides a valuable touchstone on this issue. It’s something that publishers, editors and researchers alike can look to for guidance and that will likely give it a great deal of influence over time. That’s especially true since this is a subject that external guidance is regularly sought out.

That said, concerns over copyright will continue to plague this space and that highlights a need for publishers to cooperate in this area. It’s not enough to say that fair use will protect most ethical cases of text recycling, publishers need to agree not to take legal action in those cases.

Unfortunately, this is a space where nothing comes easy and, though the TRRP has made some great progress, there’s still a lot of work to be done.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.