Understanding the Andy Warhol Ruling

Late last week, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals handed down a potentially major copyright ruling in a case that pits the Andy Warhol estate against photographer Lynn Goldsmith.

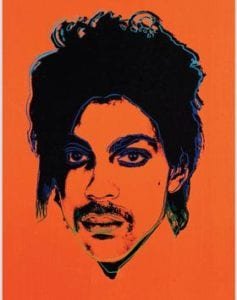

In the ruling, the court found that, as a matter of law, Andy Warhol’s Prince series was not a fair use of Goldsmith’s original photograph and, as such, is a copyright infringement of her work.

However, the decision surprised many, including myself, as the court’s previous fair use decision, the 2013 decision in the Cariou v. Prince case, was highly controversial for finding fair use despite minimal modification of the original work.

The new ruling (embedded below) is clearly aware of both the controversy in the Cariou case and the apparent contradiction to it. As such, it addresses the Cariou case heavily and works hard to contrast and compare the two cases with each other and to explain/expand upon the earlier ruling.

That alone makes this a case well worth studying but the fact that the case is from the Second Circuit, one of the most important circuits on copyright matters, means that it will be important precedent on fair use for years to come.

To that end, let’s take a deeper dive into the case and what it may mean moving forward.

Case Background

In December 1981, Goldsmith was on assignment for Newsweek magazine and took a series of portraits of the then rising star Prince. Though the shoot was cut short, she was able to capture 23 photographs including 12 in black and white and 11 in color.

Three years later, in 1984, she, through her agency, licensed one of the photos from that set, referred to as the Goldsmith Photograph, to Vanity Fair magazine for use as an artist reference. Vanity Fair then turned around and commissioned Andy Warhol, who not only created the work he was commissioned, but also 15 additional works known as the Prince Series.

According to Goldsmith, she was unaware of the additional works until April 2016, after the death of Prince. It was then that Vanity Fair reached out to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF), who inherited the rights after Warhol’s passing, to find out if they could re-license the original Warhol work. It was then that they learned the AWF had a group of 15 images and obtained a commercial license for them.

This was when Goldsmith first became aware of the full series and, in November of that year, she registered the photograph as an unpublished work. However, in April 2017 it was the AWF that filed the lawsuit first, seeking a declaratory judgment of non-infringement. This prompted Goldsmith to countersue for copyright infringement.

The case went before the Southern District of New York, which performed a fair use evaluation and found in favor of AWF, ruling that the Prince Series was a fair use as a matter of law. Goldsmith appealed that decision, taking the matter before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, where that decision has been wholly overturned.

While the actual ruling is 65 pages long, there are really two issues that are worth noting as they are the areas where the Appeals Court separated it itself from the lower court and this case from the Cariou case.

Point One: Transformation

With fair use, there are four factors that must be considered, those factors are:

- the purpose and character of your use

- the nature of the copyrighted work

- the amount and substantiality of the portion taken, and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market.

Of those four factors, the first and the fourth are considered to be the most important and it’s on those two factors that the Second Circuit had the most to say.

The first factor looks specifically at whether the use in the new work is transformative or not. However, there is near-constant debate about what constitutes a transformative work or not and, by the court’s own admission, that reached a “high water mark” with the Cariou ruling.

In that case, the court found that the bulk of Richard Prince’s images were not infringing because they were transformative enough, despite the modifications being minimal. This argument was convincing enough that the lower court, when issuing its decision in favor of the AWF, cited the case multiple times.

However, with this case, the Second Circuit worked to clarify the Cariou decision by saying that the issue isn’t the amount of transformation, but whether the new work adds “new expression, meaning, or message” to the source material.

The court used the analogy of a film based upon a book. Though the film version might change a great deal, including omitting characters, scenes or changing plot points, it’s still a derivative work based on the original because the purpose of the primary and secondary are the same.

To that end, they argued that Richard Prince’s works, despite relatively few alterations or additions, had a different purpose than the original photographs by Cariou. However, in the Warhol’s case, the works had the same or similar purpose as their source material and, accordingly, viewed the issue differently

For them, this opinion was bolstered by the fact that Warhol did not make any additions to the work and, instead, stripped away elements in order to draw greater attention to other components present in the original photograph. The judges also disagreed with the lower court that Warhol had not stripped away all protectable elements of the photograph, setting the stage for them to rule the use was not transformative.

Point Two: Harm to Potential Market

The fourth factor, to put it briefly, asks whether the alleged infringement is will usurp the original work in the marketplace by becoming a competitor or if it is a different enough work that it is in no danger of becoming a substitute, even if it becomes widespread.

To that end, the lower court ruled that the two works did not have significant market overlap, something that Goldsmith didn’t challenge. However, the Second Circuit chose to disagree with that decision regardless.

In doing that, the ruling first made it clear that, though the plaintiff has a small burden of proof to meet when discussing this factor, that the ultimate burden of proof is on the defense. Since fair use is an affirmative defense, it is up to the defense to show that the alleged infringing work does not compete with the original, not the plaintiff’s obligation to prove that it is.

To that end, the court found that Goldsmith had met her low burden but AWF had not met theirs.

As part of that, the court looked at the fact that both AWF and Goldsmith had successfully licensed their mages in similar ways. As such, there was at least some evidence that the works would be competitors in the marketplace.

The court also said that the district court overlooked the potential harm to Goldsmith’s derivative market. The court noted that many photographers license their work for others to use as a reference, as Goldsmith did originally with the image in question. Just because Goldsmith had not sought any additional licenses of that kind for the photo did not mean that the potential market was not harmed.

Finally, the court also looked at the consequences if the practice became widespread and found that allowing people to follow in Warhol’s footsteps could disincentivize the creation of original works. As such, this was another strike against AWF in this factor.

When it was all totaled, the court ruled against AWF on this factor.

Thoughts Moving Forward

The case is about as big of a win for Goldsmith as fathomable. Not only did they give her a win on every point that she asked the court to review, but they also handed her a win on points she didn’t dispute. They completely overturned the lower court’s decision, found that the artwork was infringing and further ruled that it was substantially similar (even though that was not an issue the lower court ruled on).

All of this from a court that, just eight years ago, stirred up so much controversy for taking a relaxed view on transformative use.

The decision was clearly an effort to expand and explain the Cariou decision. It talked almost as much about the Cariou case as it did the Warhol one.

The Cariou case was seen by those inside and outside the legal system as a great expansion of what constitutes a transformative use. With this ruling, the Second Circuit seems to be trying to reign that in some and put some nuance into how that ruling has been interpreted.

It will be very interesting to see how this ruling is used as precedent in other cases and if it will be cited alongside Cariou or if it will supersede it in the ongoing conversation.

Either way, this is clearly a decision of note and it should go a long way to calm the fears of many photographers that were understandably worried after the Cariou ruling.

Bottom Line

Fair use, by its very nature, is extremely complicated. It’s a subject where, the more one studies it, they less they actually understand it.

This is because court rulings can often be contradictory and, even on the Appeals Court level and above, the courts are always shifting and trying to find the best balances they can. There are no bright line rules that exist within it and the tides are constantly changing.

Still, moments like this are useful as it gives us an indication as to what the courts are thinking, and it lets us recontextualize earlier decisions. With that, we can make better guesses about what is and is not a fair use.

However, due to the nature of fair use, they will always be guesses. It’s pretty much impossible to know for certain as the next major shift is always just around the corner.

The Ruling

goldsmithClick Here to download the PDF

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.