Copyright and Tattoos

Inked up and lawyered up...

If there’s one thing that people who follow copyright law love, it’s a good “I didn’t think of that before” moment.

One such moment hit in a major way in 2011 when tattoo artists S. Victor Whitmill filed a lawsuit against Warner Bros. alleging they had infringed the design of one of his works, Mike Tyson’s face tattoo, when making the film The Hangover: Part II.

To be clear, many involved in copyright had been pondering copyright and tattoos for years prior. This includes myself and Chris Matthieu when we discussed it on a podcast in October 2007. However, the Whitmill lawsuit made the issue of copyright and tattoos a piece of mainstream news and caused those theoretical conversations to become much more practical in nature.

However, that case ended up being settled out of court without a definitive judgment, leaving us with a lot of questions, but few answers.

Over the next 9 years, the issue of copyright and tattoos continued to percolate both in and out of court with little definitive being ruled on. Though most agreed tattoos could qualify for copyright protection, the rights the person with the tattoo had was still up for debate. This was especially true for famous people who, along with their tattoos, would be featured in media of all types.

In August 2013 the NFL Players Association famously encouraged its members to get releases from tattoo artists they work with and said it would not involve itself in any such disputes.

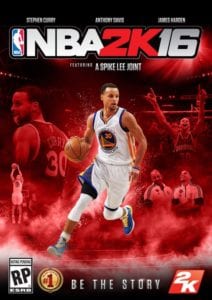

However, it wasn’t until February 2016 the issue would start on the path to a real test in the courts. In a lawsuit filed by Solid Oak Sketches against Take-Two Interactive, the tattoo parlor claimed that the company unlawfully copied their work, which was inked on to at least three NBA players, and were seeking damages.

Though the case survived a motion to dismiss, it was tossed in a summary judgment last week. The judge in the case outlined multiple reasons why he felt comfortable dismissing the case.

It’s the first definitive court ruling on the issue of copyright and tattoos. Considering that a recent poll finds some 30% of Americans have at least one tattoo, it’s an issue well worth taking a deeper dive into.

De Minimis, Implied License and Fair Use

As discussed above, the case began life in February 2016 when Solid Oak Sketches sued Take-Two Interactive of the inclusion of tattoos they created in its video game NBA 2K16.

The lawsuit survived a motion to dismiss in which Take-Two had tried to make arguments that the alleged infringement was de minimis, meaning too insignificant to be considered by the courts, and fair use. The judge dismissed both claims without prejudice, meaning they could be refiled later.

And refiled they were. After discovery, Take-Two filed for a motion of summary judgment, which the court has now granted.

To put it bluntly, the judge’s opinion is a complete drubbing of the plaintiffs in this case. The judge ultimately finds four separate reasons to toss the case, each more damming than the last.

- No Substantial Similarity: The judge found that no reasonable trier of fact could find the tattoos in the game to be substantially similar to the ones created by Solid Oak, noting that the tattoos are too small and indistinct as they appear in the game.

- De Minimis: The judge found that the alleged infringement is so minor that it is little more than a trifle and not something for the courts.

- Implied License: The judge found that the artist granted an implied license to their customers to use the work as part of their likeness. This includes, in the case of celebrities, their appearances in various media.

- Fair Use: Even after all that, the judge noted that the factors governing fair use favored the defendants in this case and that the use of the tattoos in the game was different from the purpose for which they were originally created.

Of the four arguments, the implied license is the one that will likely be most interesting to those with tattoos. The others are highly specific to the case at hand, but the implied license element could impact everyone.

Here, the undisputed factual record clearly supports the reasonable inference that the tattooists necessarily granted the Players nonexclusive licenses to use the Tattoos as part of their likenesses, and did so prior to any grant of rights in the Tattoos to Plaintiff. According to the declarations of Messrs. Thomas, Cornett, and Morris, (i) the Players each requested the creation of the Tattoos, (ii) the tattooists created the Tattoos and delivered them to the Players by inking the designs onto their skin, and (iii) the tattooists intended the Players to copy and distribute the Tattoos as elements of their likenesses, each knowing that the Players were likely to appear “in public, on television, in commercials, or in other forms of media.” Thus, the Players, who were neither requested nor agreed to limit the display or depiction of the images tattooed onto their bodies, had implied licenses to use the Tattoos as elements of their likenesses. Defendants’ right to use the Tattoos in depicting the Players derives from these implied licenses, which predate the licenses that Plaintiff obtained from the tattooists.

To summarize, the judge makes the case that, by inking the tattoo onto a customer’s skin, they grant an implied license to that person to use the tattoo as part of their likeness.

It’s worth noting that this implied license does not extend outside of the likeness. This means that the aforementioned Whitmill could have easily gone the other case as it was the same tattoo placed on a new person. However, this is bad news for the plaintiffs in a similar lawsuit filed against World Wrestling Entertainment that recently survived a motion to dismiss of its own.

While this case is likely far from over, especially with the possibility of an appeal by the plaintiffs, this ruling could wind up becoming very important guidance on the issue of copyright and tattoos.

After all, with so little legal precedent, even one judge’s opinion can become very important.

What This Means Moving Forward

This ruling doesn’t bode well for any tattoo artists or parlors hoping to take action against use (or even re-creation) of their works as part of the likeness of the person it was placed on.

This doesn’t mean it’s open season to copy tattoos though. You can’t take a tattoo you saw and then turn it into a painting or copy someone else’s work and put it on your customers. It just means that a tattoo is part of a person’s likeness and, when that likeness is copied, it can come with it.

That said, since this is based on an implied license, it could be trumped by an actual license. Theoretically at least, tattoo parlors could start requiring customers to sign away those rights. However, it remains to be seen if parlors actually feel the need to do this, if customers would agree to it or if such an agreement would hold up in court.

All in all, this balance seems pretty reasonable to me. The customer gets to use their tattoo as part of their likeness but the artist/parlor gets to control it as a work of art. That said, it’s clear that at least some tattoo artists feel that their rights should go farther and, as such, it’s unlikely this is the end of litigation in this area.

Bottom Line

To be clear, this is just one opinion. One ruling. It could be overturned on appeal. Other rulings down the road may give further guidance on copyright and tattoos and we will likely see the precedence in this area grow over the coming years.

That said, this is a question that’s been on a lot of people’s minds for nearly a decade. For others, even longer. Yet, by all accounts, this is the first real ruling on this issue we’ve seen. Even if it doesn’t end up being the final guidance, it is still important.

Copyright and tattoos is still an area to watch, but at least now we have some guidance we can point to.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.