Celebrities vs. Photographers: The Instagram Wars

The very real legal battle over your favorite Instagram users...

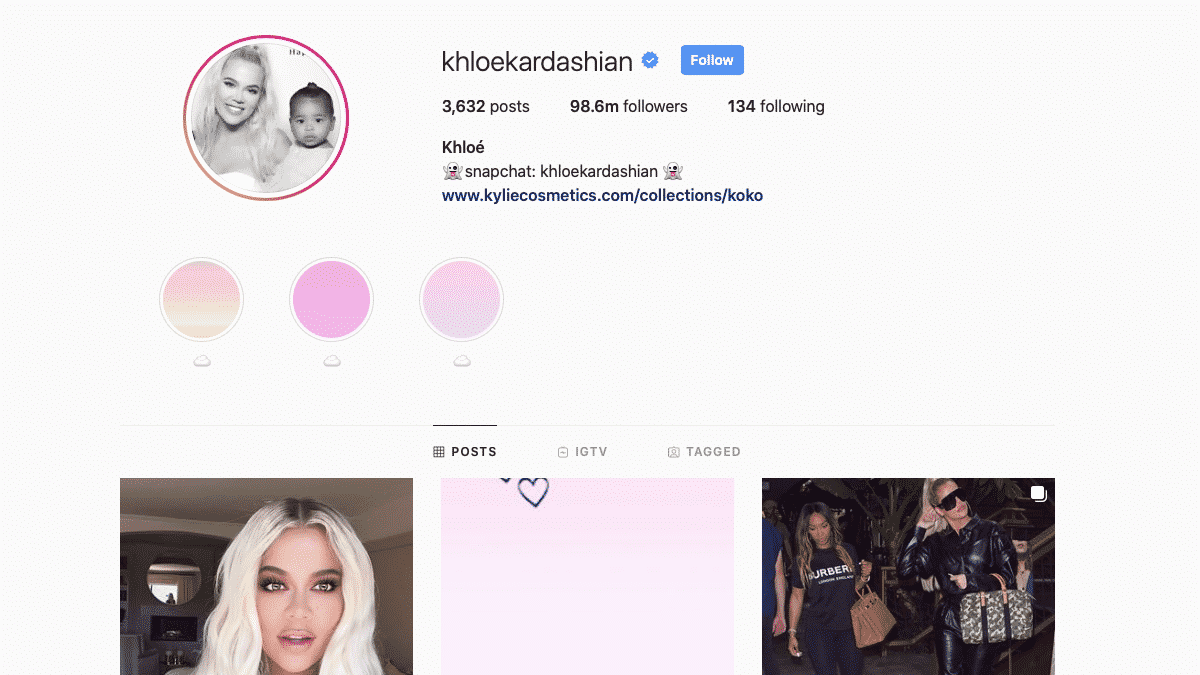

What do Gigi Hadid, Bella Hadid, Odell Beckham Jr., Jessica Simpson, Jennifer Lopez, Khloe Kardashian and dozens of other celebrities have in common?

They are all the subject of photographs that become flash point for a lawsuit after the images were posted on Instagram without the photographer’s permission.

To be clear, not every lawsuit was filed against the celebrity. Sometimes, such as in Odell Beckham Jr.’s case, the celebrity filed the lawsuit proactively. Other times, as with Bella Hadid, it was a designer or other entity that posted the photo of the celebrity and was the target of the litigation.

Still, one thing has become very clear. Celebrities on Instagram are big business and that big business is leading to some serious litigation. So much so that The Fashion Law has compiled an ongoing list of legal battles paparazzi photographers and those that have used their images on social media, primarily Instagram.

As of this writing they are tracking 21 cases since April 2017, barely a year and a half ago. While those cases represent only a tiny percentage of the lawsuits filed by photographers in recent years, they represent the lion’s share of the headlines and public attention.

But this raises a question: Photographers have had their work misused on social media since the days of Myspace and Friendster. Why is there a sudden spike in photographer litigation now? The reason is extremely complicated but there is one thing to definitely understand: Photographers are punching back.

How We Got Here: Photography and Social Media

Photographers have always had unique challenges when it came to copyright and the internet. In a print world, infringement was relatively rare as part of the benefit of licensing an image was getting a clean version of it.

In the digital world, not only is infringement as easy as a mouse click but the internet has also made photography, and all visual art, seem almost transient in nature. Photography is something to be downloaded, shared and repurposed without any consideration for the person who took the image and whatever skill, time or expense they used to create it.

But while it was annoying when it was personal people sharing over social media or other non-commercial purposes, the trend in recent years is that social media is itself big business.

On Instagram, for example, “Influencers” can make one cent per follower per sponsored post. For very popular users, such as celebrities, this can be worth tens of thousands of dollars for a single post.

This point was made in a very famous way when Jerry Media used its Instagram presence and paid influencers to promote the failed Fyre Festival of 2017. The story became a shining example of both the power and the potential for abuse such influencer marketing has.

However, even as the value and commercialization of social media posts have gone up, the treatment of photographers and photography has not necessarily improved. Though many on Instagram do behave appropriately, either sharing their work or images they’ve licensed, many others do not and routinely slip into behaviors that were tolerated in earlier days.

Combine this with services such as Pixsy that enable easier tracking of images and aggressive lawyers, such as Richard Liebowitz, and you have a formula where you’re seeing increased commercial infringement, better tracking of said infringements and lawyers willing to go after them.

You also have the U.S. Copyright Office that, despite severely limiting group work registrations for most creators, has bent over backwards to help photographers enabling them to register 750 works at one time instead of just 10.

In short, the spike in such litigation didn’t come out of nowhere. It was a convergence of changing norms with social media, better technology, more aggressive litigators and continued ease of access to the registration system. It may have only come to a head recently, but the stage has been getting set up for quite some time.

Where We Are Now

Currently, most of these cases are either currently ongoing or have been quickly settled in favor of the photographer.

There are exceptions to this rule. Gigi Hadid, in one of her three cases, emerged victorious after the court tossed the lawsuit when it was discovered the photographer in question had not properly registered the image. However, in another case where the registration was complete, she settled before the lawsuit was heavily litigated.

This has been the story pretty broadly in these cases. When the photographer has a proper registration and can show that the image was used without a license, a settlement is usually forthcoming pretty quickly.

In this vein, there’s likely a slew of cases we don’t know about because they never reach the courts and are instead handled quietly behind the scenes between the two parties themselves. Ultimately, these legal cases are likely just the tip of the iceberg.

But it’s difficult to say that this has been a pure victory for photographers.

First off, even after two years of an escalating war, little has changed in the behavior of those on Instagram. The fact that Gigi Hadid has been sued three times for copyright infringement on her Instagram makes it pretty clear that, even with settlements and the headlines, the lesson isn’t getting through for some.

Second, there’s growing resentment against photographers over this. In July of this year, a New York judge referred to Liebowitz, who also targets news agencies and other commercial entities that infringe on photographs, a copyright “troll” due to the volume of litigation he’s been responsible for.

“As evidenced by the astonishing volume of filings coupled with an astonishing rate of voluntary dismissals and quick settlements, it is undisputable that Mr. Liebowitz is a copyright troll.”

U.S. District Judge Denise Cote

Partially as as result of this, the courts are also showing less and less leeway for his efforts, even as his clients continue to extoll his virtues.

Even though photographers seem to be mostly winning (and winning without significant litigating) courts and even the public at large are losing patience. It doesn’t help that many of the cases involve paparazzi photographers, already less-than-sympathetic plaintiffs to many people, taking on popular and beloved celebrities.

The status quo looks to be untenable and it isn’t even the status quo that photographers want. However, there is at least some possibility for major change on the horizon.

A CASE Study

From the perspective of the photographers, the “troll” label is unfair. They are faced with widespread infringement of their work that is increasingly commercialized. As marketing dollars get pivoted to influencers and social media, infringement on sites like Instagram becomes a major risk to the photographers’ bottom lines.

However, currently, copyright law doesn’t give them much alternative other than legal threats, takedown notices and these kinds of small lawsuits. Currently, copyright cases can only be heard in federal court and, with that, comes a great deal of expense for both sides and questions about whether this is the best use of the court’s time.

The reason is that most of these cases are pretty cut and dry. Registration questions aside, the user either had permission to share the image or not. These cases are usually quickly settled because drawing out the matter doesn’t benefit either side.

However, these cases (and ones like it) may be better suited for copyright small claims court, such as the one that’s proposed in the Copyright Alternative in Small-Claims Enforcement (CASE) Act. The limited damages, lower legal fees and quicker resolutions make it easier for photographers to pursue these kinds of infringements without burdening themselves, the courts or the defendants.

The big criticism of the act is that the lower barriers to filing a lawsuit might increase copyright trolling. This is despite the fact that the small claims court would be opt-in, meaning that both sides would have to agree to participate.

However, as we’re seeing with photographers, the definition of who is or is not a copyright troll is somewhat fluid. Liebowitz is not a Righthaven or a Prenda Law, he represents clients whose primary business is creating and licensing creative works and are seeing widespread commercial infringement.

They aren’t relying on copyright settlements as a business model, they aren’t targeting non-commercial uses and they certainly aren’t trying to create new cases by using shady techniques such as uploading their own content to file sharing networks. The only strike against him, as an attorney, is the amount of litigation he’s filed. However, right now, mass litigation in federal court is the only legal recourse to mass infringement.

The CASE Act at least provides an alternative.

Though the CASE Act is now ready for a full vote before both houses on Congress, the odds of it passing still don’t look good given the deadlocked nature of our legislature.

Still, this isn’t the first time that the concept has come up and it seems likely to return if defeated this year. The rise in these smaller lawsuits, as well as the reaction to them, illustrates why that is the case.

The factors that created this climate for photographers isn’t going to go away and, without some kind of alternate resolution system, small claims court or otherwise, the situation is just going to get more and more untenable.

Bottom Line

Photographers have faced very unique challenges in the digital age. Though all types of creative works have seen piracy, business model shakeups and other challenges, few have seen their artistic contributions devalued like photographers.

People who wouldn’t dream of uploading a pirated film to their Facebook page or linking to a pirated ebook on their Twitter have little qualms uploading a photo they obtained from Google Image Search to their social media. While non-commercial uses have become largely tolerated, in part due to just how common they are, the increasing commercialization of social media has created a new battlefront.

To be clear, there’s no easy answer here. If the current spate of litigation has had little impact on norms it’s not likely a small claims court would change much. However, the alternatives are either the status quo or for photographers to have to tolerate large amounts of commercial infringement of their work, neither solution acceptable.

Still, until things change, expect this war between celebrities and photographers to continue and to keep grabbing headlines.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.