Twitter, Plagiarism and Retweeting

It feels like plagiarism shouldn’t exist on Twitter.

It feels like plagiarism shouldn’t exist on Twitter.

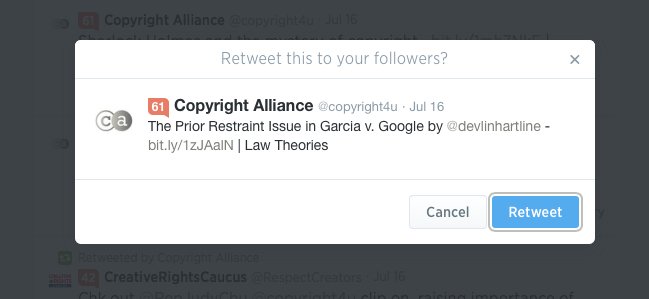

Twitter has made it easy to retweet what someone else has posted with the click of a mouse. So easy that it is almost impulsive and automatic, like it isn’t even a choice to do anything else.

This retweeting, from an attribution standpoint, is perfect. The original author’s name, avatar and formatting is preserved. The only difference between a retweet and the original tweet is the note at the says it’s a retweet and who it’s from.

But despite sharing with proper attribution being literally the easiest that it can be, plagiarism is a very serious problem on Twitter. We’ve seen studies that highlight how attribution erodes as a tweet ages and even, at one point, had a tool that tried to help users find other Twitter users who had plagiarized you.

However nothing illustrates the problem as clearly as what happened to Chris Scott, a writer and reviewer who posted a joke that went viral.

Oh hi Becky who refused to kiss me during spin the bottle in 6th grade & now wants to play FarmVille, looks like tables have fucking turned

— Chris Scott (@iamchrisscott) May 15, 2014

Though the joke, as of this writing, has over 22,000 retweets and 32,000 favorites, it wasn’t an immediate success. Over a month after the tweet was sent out, Twitter comedian Mary Charlene retweeted it to her 160,000 followers and it began to grow steadily from there.

But as the Tweet began to rack up the big numbers, as it spread far and wide it began to get increasing attention from plagiarists, who began to copy and reuse it without any attribution. The joke was also posted to other social sites, including Imgur and Tumblr, often with attribution omitted or even intentionally blanked out.

Unfortunately, what happened to Scott isn’t rare or unusual. It’s almost par for the course on Twitter and it’s a problem that’s only going to get worse in the near future.

Why People Plagiarize Tweets

People plagiarize on Twitter for the same reason they plagiarize on other social media, their blog posts and elsewhere: They want to seem clever and talented.

While retweeting is easier than lifting on Twitter, retweeting simply turns the new post into an echo chamber for someone else’s message. If you want to grow your name or improve your image, you need to post content under your name.

Unfortunately, it is easier to lift content than to produce original work, even on Twitter, and a small number of people do choose to plagiarize rather than create or retweet.

However, it may not be that simple in all cases on Twitter. First, especially when dealing with similar but not identical tweets, it’s very possible that just two or more people thought of the same idea at the same time. This is especially true of jokes being shared right after a major news event.

Second, content on Twitter doesn’t stay on Twitter very long. As Scott’s case shows, it’s shared on other social networks, sent out on email lists and told around office water coolers. Facts, jokes, statements of encouragement, etc. are shared widely on and off line but once they leave Twitter, attribution is almost always completely lost.

However, that content often returns home and what was told in a business as a joke without attribution can seem like an intentionally plagiarized tweet when someone who hears it puts it back on Twitter.

While that doesn’t explain the verbatim copies of Scott’s joke shortly after it caught fire, it might explain why some similar versions of it appeared on Twitter days or weeks later.

In short, plagiarism and attribution on Twitter is not an easy issue and it gets even worse when one looks at another hotly-debated tactic, the MT or modified tweet.

Modified Tweet or Modified Cheat?

Long before Twitter introduced and codified its retweet functionality, the Twitter community had created it’s own formatting for retweets, one that usually looked like this: RT @author TWEET

Long before Twitter introduced and codified its retweet functionality, the Twitter community had created it’s own formatting for retweets, one that usually looked like this: RT @author TWEET

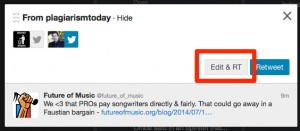

Sometimes though the retweet needed to be edited for length or content, giving rise to the modified tweet (MT), which took this format: MT @author ALTEREDTWEET

Once Twitter introduced it’s official retweet button, these two formats were largely usurped. There was no reason to take the extra time to manually retweet something, since there was no real need to edit a tweet for length before retweeting, there was little reason to use modified tweets either.

However, those standards have managed to stick around. Some of it is long-time Twitter users who do it out of habit, others don’t understand how Twitter’s retweet function works but others are just people who prefer that style.

But modified and manual retweets have come under increased attack. A recent article by Jeb Lund at The Guardian says that manual retweets (and most modified retweets) are a form of self-promotion.

The argument states that retweeting something earns the retweeter nothing but a place in the echo chamber. But, if they do a manual retweet they stand to gain retweets and favorites of their own, accolades that should have rightfully gone to the original author.

“Use someone else’s picture to drive traffic to your brand, and people get mad. Slap an RT in front of someone else’s words, and that’s apparently just how the world works,” Lund said.

While I may not be that cynical, the point is made that a manual retweet does far more for the person doing the retweeting than a normal retweet. It’s a retweet that isn’t counted, isn’t tracked and will only be acknowledged as a mention (@reply), not a retweet. Furthermore, everything that comes from the retweet will most directly benefit the retweeter, not the original author.

So while a manual retweet isn’t plagiarism, it is a more self-serving way to retweet something than Twitter’s function.

Still, there are times where modified tweets can be useful, such as when you want to add your own commentary to a Tweet or need to edit something out that might be offensive, such as coarse language. However, those cases seem to be the exception, not the rule.

For most occasions, the retweet button is the easiest and the best way to share what someone else said first on Twitter.

Bottom Line

The real problem Twitter has with attribution isn’t debates over how to retweet or malicious plagiarism of content. Rather, it’s attribution erosion.

The idea behind attribution erosion is that, as content is passed around attribution inevitably is altered and lost. This is sometimes done intentionally, but is often accidental as memories fail and the message gets separated from its identifiers.

In short, the more times a work has been shared and passed around, the less likely it is to be attributed corrected. Unfortunately, the life cycle on Twitter is so quickly that a tweet can be passed around hundreds of times in a single day.

While the retweet function makes Twitter content more resistant to this kind of erosion, it can’t do anything for those who don’t use it or cases where Twitter content is shared off site.

As the content cycle shortens, attribution is going to be one of the first things to suffer and that seems to be pretty clear when looking at what is going on at Twitter.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.