Getty Images Offers Millions of Photos for Free Embedding

Last week, Getty Images announced that it was making some 40 million of its photos available for free embedding online. According to Getty, the only catches arer that the photo has to be for a non-commercial use and that it has to use the provided embed code, which keeps the image on the gettyimages.com domain.

Last week, Getty Images announced that it was making some 40 million of its photos available for free embedding online. According to Getty, the only catches arer that the photo has to be for a non-commercial use and that it has to use the provided embed code, which keeps the image on the gettyimages.com domain.

The move, however, seemed odd to many. Getty has a long history of being strong copyright enforcers. Their product, stock photography for commercial uses, is widely considered to be very expensive when compared to other microstock sites. More importantly, they’ve been very aggressive with copyright enforcement over the years, launching a massive copyright campaign targeting businesses that used their photos without licensing them.

Getty also purchased the image tracking company PicScout in order to help it better track its images online.

However, in recent years Getty has taken a turn away from that. It updated its watermark to provide better image information, signed a deal with Pinterest and seems to have toned down at least some of the heavy-handed copyright tactics.

Despite the recent changes, the new embed tool still marks the first time that Getty has offered its images for use, under a clear license, for free. But is the license and the tool any good? I decided to dig deeper and find out.

The Terms of Service

Before jumping into the actual tool, I decided to look at Getty’s Terms of Service. The portion on the “Embedded Viewer” seems to be fairly straightforward, it makes it clear that not all Getty content will be available and that Getty reserves the right to remove content from the Embedded Viewer and, if needed, to request that you stop using it at any time.

Regarding your license to use the photos, it simply says:

You may only use embedded Getty Images Content for editorial purposes (meaning relating to events that are newsworthy or of public interest). Embedded Getty Images Content may not be used: (a) for any commercial purpose (for example, in advertising, promotions or merchandising) or to suggest endorsement or sponsorship; (b) in violation of any stated restriction; (c) in a defamatory, pornographic or otherwise unlawful manner; or (d) outside of the context of the Embedded Viewer.

Beyond that, the only real notice in the terms of service is that Getty Images will collect data on the use of the viewer, which one would expect given that the images are hosted on their server, and that they may, down the road, opt to place advertisements in the viewer without any prior notice or compensation.

In short, other than the possible risk of advertisements appearing randomly in embeds later, everything in the TOS is fairly standard. If you use the embed code as provided and for non-commercial purposes, there shouldn’t be a problem.

But even if there is an issue, for example using it in a commercial way unwittingly, Getty has already said that they will be doing little more than notifying you about your options, a stark contrast to their previous approach.

But is the embed any good and should bloggers start turning to Getty for their photos? I decided to give it a try and find out.

Testing the Embeds Out

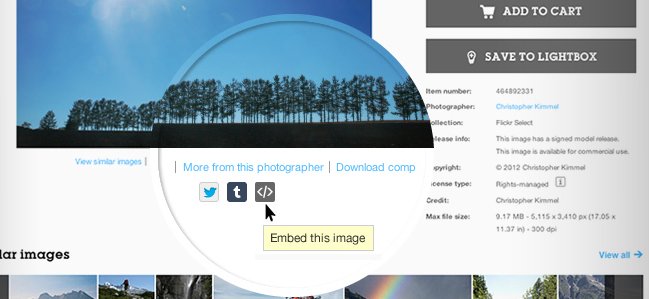

The process of embedding an image on your site is very easy. All you have to do is first find an image that’s available for embedding. This can be done by doing a search on Getty’s site and hovering over the images, looking for the embed symbol.

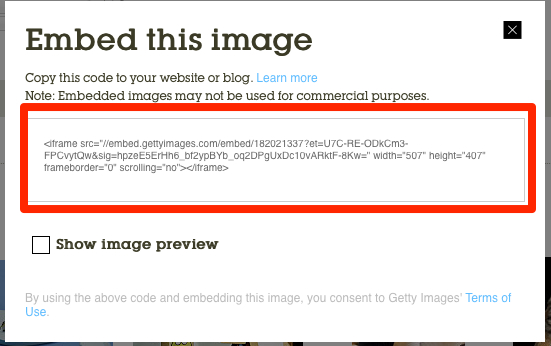

Once you click the button, all you have to do is copy the HTML code and then paste it into your post.

And then you can see the results below:

The resulting image appends attribution to the photo, including the name of the photographer and Getty itself. It also provides links to post the image on Tumblr, Twitter or to embed it again elsewhere.

But while the process is simple, it may be a bit too bare bones to be of much use.

When you go copy the HTML code, there are no options to resize the image, to align it or add a caption to it. Furthermore, the attribution size is very large and needlessly bulky. Considering there are free stock photos at sites like Morguefile and StockXchng and tools such as PhotoDropper to make adding Creative Commons-Licensed photos into your work easier, there’s little benefit to using Getty’s photos.

Fortunately, Getty admits that this tool is in its early stages and has said that it will be working on it based on the feedback it gets. On that front, allowing resizing and repositioning seems to be a great place to start. While it would be pretty trivial to align the embed using HTML, there’s no way to resize the image without violating the terms of service that Getty has set down.

Update: As shown by PetaPixel, since I started work on this piece Getty has changed the tool so images can be resized by editing the HTML, this was done to prevent users from cropping out the attribution. However, it doesn’t actually reduce the image size, just the size it is displayed.

But despite all of these limitations and problems, it’s still a major step for Getty, even if it is only a half measure.

Half Measures, No Solutions

At SXSW I attended a panel entitled “How Open Licensing is Transforming Design“, which featured representatives from Creative Commons, Adobe (through Behance), Autodesk and the Noun Project, an icon project that creates open-licensed images.

I asked the panel what they thought about Getty’s move and Elliot Harmon at Creative Commons said that it was, “An interesting half-measure,” which it definitely is.

But it is just that, a half-measure. Getty is dabbling with open licensing, but only in the most restrictive way possible, through the use of forced embeds that may turn into advertising spots down the road.

As a result, it’s a move that seems to have made no one happy. Open source license advocates are upset at the lack of a Creative Commons (or similar) license while those who favor more strict control are loathe to see the images made available for free in any context.

There are even those who believe that the move is a push by the Carlyle Group, the private equity firm that owns Getty, to pump up Getty’s price for a potential selloff.

So while the news headlines have been rightly trumpeting the new embed tool as a major change for Getty, there’s actually a great deal of discontent over the service. Photographers are worried about how this will impact their bottom line, especially considering Getty isn’t offering them an opt-out, open licensing advocates dislike the lack of a true open license and users are left with a very limited and clunky embed tool that could start placing ads on their site at any time.

Because of this, Harmon said that hoped Getty would see the value of sharing to their brand and take this initiative farther, but others are worried that it may have gone too far already.

Time will be the true judge.

Bottom Line

If you’re a webmaster or a blogger looking for some images for your posts, Getty probably isn’t the place, at least not right now. Only a fraction of Getty’s images are available, the embeds are too clunky to be effective, the attribution too large and the threat of forced advertising is always looming.

There are much better, easier tools for getting free images into your site. While those tools might not have Getty’s images, they almost certainly have something that you can use.

If you absolutely have to have one of Getty’s images on your site and paying for it is not practical, then the embed tool might be a good approach depending upon your use. However, bear in mind the risks and challenges that you’ll face and that, at any point, advertising could appear with the image.

If that’s acceptable to you and your site, by all means go ahead.

As for Getty, this move has certainly attracted a lot of publicity and attention, but has done little to satisfy the company’s critics, including photographers worried about pricing and copyright reformers who loathe Getty’s practices.

Like a half opened door, it frustrates both those who want to keep others out and those who want to come in.

Getty needs to either improve the tools it has or rethink its strategy if it wants to see much use from this. The benefit, for everyone, is minimal right now.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.