Copyright and the Legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

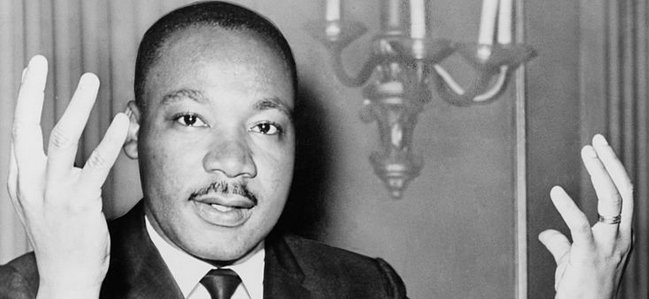

Today marks the 50th anniversary of one of the most powerful, meaningful and important speeches in U.S. history. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

Today marks the 50th anniversary of one of the most powerful, meaningful and important speeches in U.S. history. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

It’s nearly impossible to overstate the importance the speech had and continues to have on the civil rights movement, race relations and U.S. history in general. That 17-minute speech, given on August 28, 1963, continues to echo today with people of all stripes.

However, use of the speech is still strictly limited. Though King’s heirs have made the speech available for educational use, or at least declined to take action against educators, they have a long history of taking legal action against others who use the speech, including TV stations, newspapers and documentaries.

This has led to criticism from other civil rights leaders and has made it difficult for others to use the speech, even as they seek to honor it on the 50th anniversary.

Though the impacts of this enforcement are clear, including limiting access to the speech online, it also has sparked a separate copyright debate. That debate reached something of a climax in Jaunary of this year when, on the one year anniversary of the defeat of the Stop Online Piracy Act, some copyright activists posted illegal copies of the speech online to celebrate “Internet Freedom Day”.

This makes it worthwhile to not just take a look at the impact the speech has had on our nation’s history, but also on copyright and just how the protectionist approach the King estate has taken has impacted copyright law itself.

The Copyright History of “I Have a Dream”

According to most sources, though Dr. King had a speech prepared, many elements of the iconic speech were improvised, including the famous “I have a dream” lines. As such, Dr. King didn’t register the speech before giving it and didn’t immediately afterward either.

It wasn’t until unauthorized copies of the speech began to appear for sale that Dr. King registered the speech. He ten used that registration to secure injunctions against at least one person selling unauthorized recordings.

But even after the work was registered and had seen a test in the courts, there were serious questions about whether or not it was actually copyright protected.

Under the law at the time, works that were published without meeting certain criteria, including a copyright symbol and registration, were considered to be in the public domain. This, for example, is how the film “Night of the Living Dead” ended up in the public domain.

However, that copyright issue would not be resolved until well after Dr. King’s death. In 1999 his estate sued CBS after the network produced a documentary that featured portions of the speech. The lower court granted a summary judgment in favor of CBS but the 11 Circuit Court of Appeals reversed that decision and sent the matter back to the lower court to rule on issues of infringement.

CBS had argued, successfully at first, that the way King gave the speech, in front of a large audience and with widespread media coverage, amounted to a publication. However, the court found that it was actually a performance of the work, no matter how broad the audience is, and that the speech was still unpublished at the time it was registered.

The case, however, never made it to a final verdict. It was settled before any conclusion could be reached. Still, the ruling was enough to clear up the copyright issues and, with that clarity, the King estate will continue to hold the copyright in the speech until 2038, seventy years after Dr. King’s death.

Though the King estate has made many of Dr. King’s documents, including the “I Have a Dream” speech, available to the public in a digital archive, the format is less-than-ideal for viewing, a series of scanned images of a pamphlet.

Videos of the speech and text transcripts can be found online (in particular right now) but they have been historically scarce as the King estate has consistently sought and obtained removal of unauthorized copies.

Legally, this is their right. However, that doesn’t mean that many are not upset with the King estate and the way it has limited access to Dr. King’s most famous moment.

The Copyright Debate

While I am a strong supporter of copyright, I also acknowledge and believe that there are things much more important than copyright. Though “I Have a Dream” is certainly a copyrighted work and entitled to the protections thereof, it’s also a cornerstone to U.S. history and has great significance beyond the commercial interests copyright law usually involves itself in.

In short, it is much more than a copyrighted work.

This makes it tempting to say that it should be placed in the public domain or that the public should have special rights to the work because of its importance. It would be nice if documentaries could trivially feature more of the speech, if newspapers could print the whole transcript, etc. without fear of violating copyright law.

But that raises serious problems and questions. When does a work become too core to our culture to receive full protection? How do we decide which works to take rights away from? Would such a rule cause artists to try and avoid such a classification?

Copyright law, for the most part, tries to avoid answering questions about what is and is not art. The standard for copyrightability is very low, basically meeting a requisite level of creativity and being fixed into some tangible medium of expression. This qualifies everything from your doodle on a napkin to an epic novel for protection.

Unfortunately, adding an extra layer of complexity to the law to try and free up works like “I Have a Dream” is probably a futile exercise. It would only create more uncertainty and, due to legal costs, wouldn’t likely have the desired effect, similar to how legal costs have, until recently, prevented a meaningful legal challenge to the copyright status of “Happy Birthday to You”.

Any change in the law to target works like Dr. King’s speech would have to effect all other copyrighted works. However, that risks other unintended side effects and drafting broad legislation to deal with rare exceptions is, generally, bad policy.

Copyright law, no matter how it is changed, should be written for the greatest benefit to the most people, not to deal with exceptions. Because, while exceptions and outlying cases get a great deal of coverage, they are only a tiny fraction of what copyright has to help deal with on a daily basis.

In short, while “I Have a Dream” is a great opportunity to talk about the role of copyright in our society, changing the law to free it is simply not a wise move.

Bottom Line

In situations such as this one, copyright holders, whether the original creators or their heirs, are in a difficult position. Though the work itself was likely created with great effort and work and has, through that, come to have great value and meaning, it also a deeper importance.

However, to a lesser degree, this is true of all popular copyrighted works. While Mickey Mouse and Harry Potter may not be as historically significant as “I Have a Dream” they are still key parts of many people’s lives, are a major part of our culture and have a deeper importance beyond their commercial use.

Copyright law gives rightsholders the power to exploit those works, including in ways that may be damaging to their legacy and their deeper meanings. However, it also gives rightsholders the ability to protect them and secure that legacy for a long time to come.

In the end, the onus is really on the rightsholder to find the right path for the works they control. While this is hard enough for any new work, it’s much more difficult for those with the weight of legacies to think about.

While that might seem to be an enviable problem to have, as the criticism of the King estate shows, it can be a severe burden as well.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.