Debunking Jayson Blair’s Book

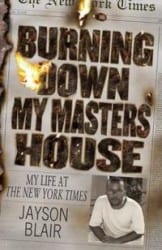

Earlier this week, I wrote my lengthy review of Jayson Blair’s memoir “Burning Down my Masters’ House”. If you haven’t read it, you may want to go back and get a more in-depth understanding of what’s inside it.

Earlier this week, I wrote my lengthy review of Jayson Blair’s memoir “Burning Down my Masters’ House”. If you haven’t read it, you may want to go back and get a more in-depth understanding of what’s inside it.

As I said in that review, I had picked up the book hoping for answers and explanations. The question of why people choose to plagiarize has befuddled experts for as long as there has been plagiarism. A book, possibly written in a moment of honesty by an admitted plagiarist, seemed like an excellent opportunity.

However, Blair’s book was a missed chance at that.

Much of the book seemed to be not so much about his actions, but rather, an airing of dirty laundry of The New Yorks Times and journalism as a whole. Instead, Blair’s “confessions” centered around his problems with alcohol cocaine and bipolar disorder and it presented those confessions in a way that attempted to make him more sympathetic.

When it comes time to talk about his misdeeds, including the article that got him caught, he almost glosses over it, saying he was in a period of psychosis (or something similar) at the time and couldn’t remember what he was doing.

However, all of Blair’s excuses are either false or irrelevant and it’s easily proved. Jayson Blair’s book isn’t about coming clean, but about changing the dialog around him and blunting the scorn others say his name with.

Unfortunately for Blair, I’m not buying it and neither should you.

The Jailbreak Problem

Imagine you ran a large prison, one with about 2,000 inmates. One day, two inmates make a run for it and jump the fence. After a manhunt both are caught and brought back and, in their interrogation, are asked why the did it.

Inevitably, the two men will start listing familiar excuses about how they couldn’t stand being on the inside, how they missed their families or they wanted the comforts of the outside world. While these probably were the factors that motivated them, they are equally true for the other 1,998 inmates in the prison.

So the question is unanswered: What made these two inmates break for it and not the others?

Jayson Blair does a lot of this in his book. He sets up a variety of factors that he at least implies contributed to his misdeeds. Those include:

- The high-pressure environment at The New York Times.

- Office politics at the paper.

- The emotional toll of Sept. 11 and the events after.

- The challenges of being thrust into such an important role (lead on the Beltway Sniper case).

- Race issues that, he claims, put additional pressure on him.

The problem is that every single one of those things can be said about others at The New York Times. Everyone at the paper had to live with the pressure cooker it could be, office politics affected everyone (and they do so at every job, not just The Times) and everyone at the paper during that time lived through the same post 9/11 challenges and many have faced assignments out of their depth.

Even the race issues become irrelevant when you factor in that there are other black reporters at The New York Times, including some he referenced in the book. While it may be true that there are race issues at the paper, there have been reporters of every race that have thrived there and managed to do so without plagiarism or fabrication.

Though Blair pitches his time at the paper as something of a perfect storm, one of race, job stress, chemical dependency and bipoloar disorder. There were many other reporters at the paper living through the same storm (Blair often focuses on other reporters with similar addictions to his) and they haven’t found themselves the subject of a lengthy front-page correction.

So what makes Blair different? Well, he does offer up a few theories but those don’t hold up well either.

A Whole Career of Lies

In the book, Blair basically bills his downfall as the story of a young, somewhat naive, reporter who is both hard working and intrepid but becomes disillusioned with journalism after seeing it first hand. While that is going on, he is battling a growing alcohol/cocaine problem, and endures the events of 9/11 and, after making some progress with his recovery, is thrust into a job he doesn’t want, namely the lead on the Beltway Sniper case/trials that separated him from his support structure in New York. Because of all of this, he has something of a breakdown and goes on a months-long plagiarism/fabrication spree in early 2003.

Whether or not the facts of all of this is accurate is irrelevant. Blair is leaving out details that would paint a very different picture.

While it is true that, initially, nearly all of the attention was on Blair’s early-2003 misdeeds, the scandal quickly widened a great deal.

To be clear, early 2003 was when Blair was at his worst. It was when he was claiming to be places he wasn’t and lying about interviews he never gave did and using photographs and other reporting to fill in his blanks. But his misdeeds go back much farther than that.

For example, in additional corrections put up in June, it was revealed that Blair had lifted passages in a story that he had written in May 2002, almost a year before the scandal broke.

However, according to the New York Times review/rebuttal to his book, The Boston Globe, where Blair interned before he had ever set foot in The New York Times, a full five years before his “break”. That fact is never mentioned in the book and, in truth, The Boston Globe only gets a brief at all.

In fact, claims of unethical behavior in journalism go all the way back to 1996 and his time at The Diamondback, the college paper of The University of Maryland. There, he was accused of fabricating quotes, erratic behavior and mismanaging finances as the editor of it.

Blair resigned from the paper citing “personal reasons” shortly after staff members at the paper complained to school officials.

But in truth, you don’t need those outside sources to find this proof. Blair himself talks in the book about how he slept with a representative of an unnamed company in exchanging for several regular mentions of them in the paper and about his love for joyriding in the company car. However, in the book, he made light of these things and discussed them jokingly, as if there was nothing wrong with them at all.

Blair’s misdeeds and ethical problem run much deeper than the first quarter of 2003 and he wasn’t prepared to talk about that in his book.

The Wrong Demons

The one thread that is present throughout Blair’s journalism career, besides unethical behavior, is his his chemical dependency, namely alcohol and drugs, and his bipolar disorder (which was only diagnosed after the scandal broke).

Here again though, we return to the jailbreak problem. Blair wasn’t the only person battling these demons.

In his book, Blair talks regularly about drinking and doing drugs with other members of the Times’ staff. He also wasn’t the only reporter at The Times who was battling bipolar disorder (diagnosed or otherwise) and he certainly wasn’t the only reporter in all of the world. Yet, somehow, he was the one who plagiarized, fabricated and lied in order to further his career.

Without getting into a discussion of what bipolar disorder is and how it impacts people, the truth is that most people who suffer from it (diagnosed or not) are honest, hard-working and do their best to cope with their condition without violating the the rules of their profession or society at large.

It’s clear that Jayson Blair’s problems with ethics run much deeper than his chemical problems and his other stated demons. They lie on a level he didn’t directly touch on in this book. However, he may have offered some glimpses into it.

Between the Lines

So, if none of Blair’s given reasons add up, what about the reasons that lie between the lines? The ones not expressly mentioned?

In the book, Blair talkes a great deal about various unethical acts including, as mentioned above, trading news coverage for sex, misusing the company car, lying to others and manipulating others to meet his goals.

Though it’s easy to dismiss some of this as things a journalist has to do to get leaks and scoops, much of it is without reason. It’s clear that Blair is (or at least was) a person with a strained relationship with the truth, a feeling that was backed up by his colleagues at The Diamondback.

Why Blair has this issue is difficult to say, but another hint comes from his descriptions in the book. Blair was often very brief with his descriptions of people. There were some individuals in his book referenced almost completely throughout that I had no idea what they looked or acted like. Other than race, he barely told us anything about the other people in his story.

This could be chalked up to bad writing, a journalist trying to write a novel, but Blair did describe in detail one group of people, the other patients at a psychiatric hospital that he stayed at briefly following the breaking of the scandal.

However, there the descriptions behooved him. The other descriptions gave the reader the sense of seriousness of Blair’s condition and just how far he had fallen. Describing carefully the others around him would not have had this benefit. They would have humanized the people he hurt and made him appear more like a monster. It was best if most people in the book remained mostly faceless and Blair made it that way.

In short, the word I would use to describe Blair based upon the impression I got of him from his book and my subsequent research is “manipulative”. Blair likely does have other serious demons, but he has shown throughout his journalism career that he was willing to manipulate others to his benefit and abuse the trust placed into him for his gain.

Why that is, only Blair himself might know. But that was not something he dove into in his book.

Bottom Line

We are rapidly coming upon the ten-year anniversary of the Jayson Blair scandal. Blair has not worked as a journalist for nearly a decade and, instead, has found a new career as a life coach and has also done non-profit work related to bipoloar disorder.

I believe strongly that, given time and motivation, people can change. Though, at the time of his book, Blair wasn’t ready to be totally honest and was continuing his manipulative and deceptive ways, I’m hoping that in the nine years since its publication things have changed for Blair.

In one of his most recent interviews, one about the Jonah Leher case, Blair seemed to be at least somewhat more honest saying that, “I don’t think I’ve ever been able to really successfully analyze why I did what I did. Obviously, in my case there was a little bit of mental illness at play. That’s obviously not the reason it happened.”

He also talks about how there isn’t a lot of premeditation and “firewalls” that, once they come down, make it easier to do a misdeed a second and a third time.

Still not a robust explanation, but certainly closer to the truth and more relevant.

However, it’s clear that the “firewalls” came down early in Blair’s career, before many of the factors he cites came into play. Still, the years seem to have inched us closer to the truth and maybe, just maybe, with the ten-year anniversary approaching, he may be finally ready to give some meaningful answers.

If he is, I’d love to help ask the questions.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.