Looking at The AMBeR Benchmark Plagiarism Tariff

When it comes to plagiarism enforcement in academia, there’s a very serious problem: Inconsistency.

When it comes to plagiarism enforcement in academia, there’s a very serious problem: Inconsistency.

The problem is simple. When a student, researcher or even a professor are accused of plagiarism, the punishment they can expect is, usually, far from set in stone.

It’s very easy for two students to commit two very similar acts of plagiarism on nearly identical assignments and receive wildly different disciplines. While this can certainly happen internationally, it can even happen among schools in the same region and even within the same institution.

Educators have long since talked about the need for a more consistent and simpler way to enforce plagiarism rules, but seemingly little progress has been made. Schools, for the most part, still weigh the cases individually and without much thought to how similar cases were handled, leaving the door open to unfairness and mistakes.

However, for over eight years now, researchers in the UK have been working hard on trying to find a solution to this problem. That solution is a tariff (tariff meaning, in this case, a schedule of rates or charges) that is objective rather than subjective and works to help instructors and school officials both standardize enforcement and simplify it.

While it’s not perfect and has weaknesses, the idea behind it has the potential to drastically reshape plagiarism enforcement and help bring a bit more clarity and fairness back to the process.

The History of the Tariff

As a result, various government and higher education organizations began researching the issue and concluded that there was a vast amount of variation between different institutions (and within different units of the same institutions) in the penalties for plagiarism.

One of the agencies involved in that research was the Academic Misconduct Benchmarking Research (AMBeR) Project, which also set about creating the Benchmark Plagiarism Tariff. Researchers Peter Tennant, a research assistant from Newcastle University, and Gill Rowell, academic adviser at plagiarismadvice.org, did just that and announced their results in 2010 at the 4th International Plagiarism Conference.

At the 5th International Plagiarism Conference (previous coverage of this day), held last month, Rowell, now with iParadigms Europe, along with Dr. Jon Scott and Dr. Jo Badge, both from the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Leicester and Margaret Green from the School of Health Science, at the University of South Australia, conducted a follow up study (PDF). The study looked at past cases of plagiarism that were concluded and re-evaluated them using the tariff.

The results were promising. Most of the cases fell within the guidelines of the tariff and those that didn’t, for the most part, were due to the punishment being metered out not being one discussed in the tariff, such as reducing a grade or a partial grade.

This is a sign that the tariff, while imperfect, may be ready for more widespread use, both in the UK and abroad.

What is the Tariff?

AMBeR chose what to focus on with the tariff after discussing the matter with educators. As a result, the completed tariff, which you can read here, focused on five key areas:

- History: How many times has the student been caught plagiarizing?

- Amount/Extent: How much of the work is plagiarized?

- Student Level/Stage: How far along is the student in school?

- Value of the Assignment: How important was the assignment in terms of the student’s grade?

- Additional Characteristics: Did the student attempt to hide the plagiarism and other miscellaneous factors.

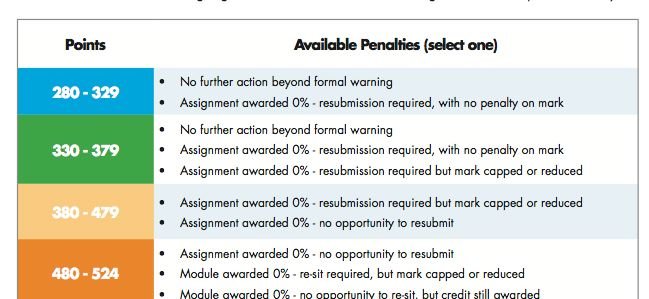

From there, the students’ scores are tallied and they are assigned a punishment ranging from blue to black. Blue being a mere formal warning and black being (up to) expulsion.

Ideally, if everything went as according to plan, the punishment recommended by the tariff should be the same or almost the same as the one that would have been recommended normally.

Why Use the AMBeR Tariff?

The reason to use the tariff is pretty straightforward. It’s much more consistent and much more easy than the current methods of determining punishment for plagiarism.

The tariff itself is just two pages: One page for the questions and their point values and one for the scale of punishments. The instructor, administrator or other official only needs to answer five mostly quantifiable questions about the plagiarism and tally the points. From that, they should have a good idea of where the infraction falls on the punishment scale.

If you have all of the facts of a plagiarism case before you, it only takes a few moments to determine the punishment that the tariff recommends.

What are the Weaknesses of the Tariff?

As you might expect, this simplicity and balance comes with tradeoffs and there are going to be weaknesses in any such system. Many of these are openly recognized by the researchers who built it and some may be addressed in future revisions.

- Collusion: The system is not designed to deal with collusion, cases of students working inappropriately together on the same assignment. This is a broader problem across all education though.

- Extenuating Circumstances: What happens if the plagiarist recently suffered a death in the family? Offered up a heartfelt confession/apology? Etc. The tariff doesn’t weigh anything that takes place outside of the act itself.

- Long-Term Impact: In some professions, even a single allegation of plagiarism in college can be destructive to the student’s career for life. The tariff does not weigh the long-term impact of any punishment.

- Different Types of Plagiarism: The tariff is built for verbatim plagiarism but may not adequately address other types, such as source plagiarism, plagiarism of ideas, etc.

- Some Room for Judgment: Though the tariff works to remove most of the human error out of the process and succeeds, there’s still some discussion to be had about what the value of the assignment is and whether there was an attempt to hide the plagiarism. In short, two people can use the same tariff and come up with different scores.

Bottom Line

Is the AMBeR Benchmark Tariff perfect? No. However, no system like it ever will be. Much like copyright law itself, there’s no way a simple set of rules can represent the whole spectrum of possibilities that come from this kind of situation.

However, the tariff is probably the best tool available for standardizing and simplifying the process of disciplining plagiarists.

While it’s too soon for the tariff to be the sole arbiter of what punishment that a plagiarist receives. Schools should definitely be aware of the tariff and start looking at it as they’re dealing with cases of plagiarism. Since it only takes a few moments to run a case through the tariff, it makes sense to ask “Does our planned punishment match the tariff’s and, if not, why?”

Thinking about and using the tariff now not only can help schools improve their plagiarism enforcement practices, making them more consistent and streamlined, but also can help the tariff too as feedback is going to be critical to making the tariff better and better.

But even if the AMBeR Benchmark Plagiarism Tariff doesn’t become the gold standard for plagiarism enforcement or if it only is used locally in the UK, the idea behind it could prove to be much more powerful as other schools and institutions can use the concept to create their own variations that, even if they aren’t consistent with other school, are at least internally consistent.

That, in the long run, would be a huge step forward.

Presentation

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.