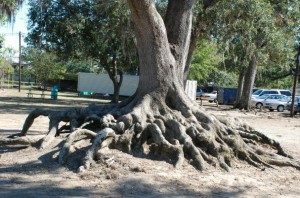

Getting at the Root of Academic Plagiarism

Note: This is a guest post written by Dorothy Mikuska, a owner of PaperToolsPro. Views or opinions expressed in this piece may or may not reflect my own. If you are interested in guest blogging for PT, please see these guidelines and contact me here.

Note: This is a guest post written by Dorothy Mikuska, a owner of PaperToolsPro. Views or opinions expressed in this piece may or may not reflect my own. If you are interested in guest blogging for PT, please see these guidelines and contact me here.

Academic plagiarism is a challenge to educators as the expanding use of online sources has facilitated intentional and unintentional copying. The only remedy is to root out its cause, not just deal with its symptoms. Plagiarism actually begins in the fast, distracted way that students—middle school to graduate school—read from screens.

Although catching and punishing offenders has been the approach most schools use to contain plagiarism’s proliferation, the real solution lies in teaching students to read slowly and deliberately from electronic sources as they have learned to read from paper.

Fast, Distracted Reading

Screen readers read fast and distractedly, scrolling and clicking rather than slowly reading, annotating, and reflecting on the text.

Pop-up windows, flashing ads, hyperlinks, sidebar menu advertisements are designed to point the reader’s attention rapidly away from the text to the ads from which websites and search engines make their profits.

Electronic textbooks, even if not connected to the Internet, divert attempts at in-depth reading to a picture, a video, another page, or a definition.

Some diversions only appear to enhance comprehension. For example, clicking a link to a definition doesn’t develop vocabulary from context, but merely teaches students they don’t ever have to learn the word, just click. Whether useful supplements to reading or unnecessary distractions, these diversions interrupt the learning process and the habit of focused reading.

When A Word Is Not a Word

We assume that reading words on a clay tablet, a scroll, a page of a paper book or on a screen is the same because a word is a word. However, our eyes move differently reading on paper than on screens. Jakob Nielson’s research that tracked eye movements found that paper readers follow an E pattern: they move across the first line of text and sequentially across every line to the bottom of the page.

The eyes of screen readers follow an F pattern: they read the first line, part of the next, then skim and scroll to the bottom of the page or click a link.

Nielson further found that 84% of screen readers process words and sentences out of sequence and read only 18% of the text. This fragmented reading results in little comprehension of the material students must understand, synthesize, organize around emerging patterns of ideas, and explain in their own words and voice. Lacking this understanding, they are compelled to copy.

According to brain researcher Maryanne Wolf in Proust and the Squid, the brain does not just read differently, but it thinks differently depending on the medium. Paper reading activates deep white cells where long-term memory and feelings reside; electronic reading over-activates surface grey brain cells, which seek immediacy and efficiency and where decoding takes place.

For screen readers, the milliseconds that the brain needs to access long-term memory for learning to occur is instead used to reroute attention to decoding or skimming information superficially.

After the first five hours of screen reading, the neural structure of the brain changes permanently and that changed brain wants only to skim and decode. The reading brain that wants to understand the text, and not plagiarize, must be retaught the skills of deep, fluent reading—annotation, rereading, and reflection—after those initial five hours of screen reading.

The Challenge of Complex Text

Fast, distracted screen readers expect information to appear in small chunks, nicely diced and prepared for them. They seek short, simplistic ideas and multiple-choice kinds of answers to complex questions; they want information explained and reduced to the simplest ideas as quickly as possible.

With these expectations nurtured by electronic reading, complex text—whether a modern novel like Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, a scholarly journal like Nature or Science, a legal document, or a logical argument—becomes an impossible challenge because screen readers’ minimal experience with complex text has left them unprepared.

Diploma to Nowhere (PDF) reported that of the 3 million freshmen entering college in 2008, 43% at 2-year public colleges and 29% at 4-year public colleges were unable to do complex college assignments. The National Endowment of Arts (PDF) reports that 55% of high school students spent 1 hour or less reading or studying for class, and 56% read 1 hour or less for leisure. Once in college, during the school year 74% of college freshmen and 80% of college seniors read 0-4 unassigned books related to course work, their major, or leisure reading.

Students with minimal reading experience are less prepared for reading the complex material required for doing academic research. Using their skills at finding fragmented information from their non-sequential reading have made students expert at information retrieval, not knowledge formation. With little understanding of the information they find, they copy, slightly edit whole passages with ellipses and synonyms, sometimes without attribution, and feel absolved of any plagiarism.

What Works

The solution to plagiarism is slow, deliberate reading that invests students in their research. Students need to be taught to reflect on small sections of text, write notes in their own words and voice, connect to what they already know, ask questions—all the paper reading strategies that encourage the brain to use those milliseconds to go from decoding to accessing long-term memory and learning.

Functioning like intellectual training wheels, research management software that forces students to employ the strategies of slow, reflective reading and careful note taking, can prevent plagiarism. With a stake in their reading, thinking, recording, and writing processes, students of all ages would no longer feel the need, or the desire, to plagiarize.

Biography

Dorothy Mikuska (B.A. in English, Loyola University; M.A. in English, Northwestern University; and C.A.S. in Educational Leadership and Supervision, National Lewis University) taught high school English including the research paper for 37 years. After retirement she formed a company, ePen&Inc, and created PaperToolsPro, software for students to employ the literacy skills of slow, reflective reading needed to write good research papers. She has spoken at conferences such as The International Conference on the Book (St. Gallen, Switzerland), National Conference of Teachers of English, Illinois Association of Teachers of English, Illinois School Media Association, and Illinois Computer Educators. She currently blogs at The English Teacher’s Notes Blog.

Dorothy Mikuska (B.A. in English, Loyola University; M.A. in English, Northwestern University; and C.A.S. in Educational Leadership and Supervision, National Lewis University) taught high school English including the research paper for 37 years. After retirement she formed a company, ePen&Inc, and created PaperToolsPro, software for students to employ the literacy skills of slow, reflective reading needed to write good research papers. She has spoken at conferences such as The International Conference on the Book (St. Gallen, Switzerland), National Conference of Teachers of English, Illinois Association of Teachers of English, Illinois School Media Association, and Illinois Computer Educators. She currently blogs at The English Teacher’s Notes Blog.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.