How Universal Re-Copyrighted Frankenstein’s Monster

Previously this month, we talked about how a copyright blunder led to Night of the Living Dead being released into the public domain and how a copyright dispute nearly led to the destruction of Nosferatu, now regarded as one of the best early vampire films and created much of the modern vampire lore.

Previously this month, we talked about how a copyright blunder led to Night of the Living Dead being released into the public domain and how a copyright dispute nearly led to the destruction of Nosferatu, now regarded as one of the best early vampire films and created much of the modern vampire lore.

However, this week’s post is a bit of a twist. Rather than it being the tale of something falling out of copyright or a copyright dispute nearly destroying it, we’re talking about how a movie studio, namely Universal, managed to effectively re-copyright a previously public domain creature: Frankenstein’s Monster (Note: For those who are unclear, Frankenstein is the last name of the doctor, the monster has no name.)

How did this happen? Much the same way that Disney has managed to exert a great deal of copyright control over public domain stories such as Pinocchio, Snow White and Cinderella: By creating a movie retelling of the story that adds copyrightable elements they can control.

It’s a simple plot, but on that has helped to largely keep other re=tellings of Frankenstein off the shelves and out of theaters.

Resurrecting Frankenstein’s Monster

Mary Shelley first penned Frankenstein in the summer of 1816 during her famous summer with Percy Shelley and Lord Byron. The first edition was published in 1818 though it was published anonymously. It was only on the second printing, in 1823, that she would be credited as the author.

Mary Shelley first penned Frankenstein in the summer of 1816 during her famous summer with Percy Shelley and Lord Byron. The first edition was published in 1818 though it was published anonymously. It was only on the second printing, in 1823, that she would be credited as the author.

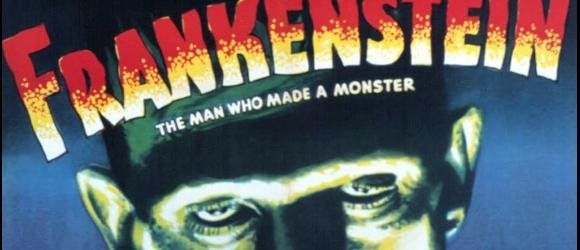

By 1931, over a century later, Frankenstein had long lapsed into the public domain and became ripe pickings for Universal Studios, which had just found a strong success with it’s film “Dracula”, starring Bela Lugosi, and was seeking to expand its line of monsters.

However, in adapting Mary Shelley’s classic tale to the silver screen, Universal had a problem: The original book was largely devoid of of any real description of the monster, leaving most of the details to the reader’s imagination. In fact, only a few lines were spent on the moment the monster came to life, meaning the iconic scene with lightening, maniacal laughter and scifi-looking equipment didn’t exist in the book.

As such, Universal had to craft an image of what it thought the monster should look like and, through the magic of make up and 1930s special effects, turned actor Boris Karloff into a flat topped, lumbering giant with two bolts and a prominent scar.

The look became an instant sensation and became widely associated with the monster. It was used in the subsequent sequels including The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Son of Frankenstein (1939) Ghost of Frankenstein (1942) and many others. But more importantly, it became the default “look” for the monster and how most people envisioned it.

Even today, if you ask someone randomly to describe what Frankenstein’s monster looks like, you’ll probably get a description that mirrors Universal’s version.

However, since that look wasn’t in the original story, Universal could control it’s particular vision of the monster and enforce copyright in it.

And control it, it has.

Controlling the Monster

Since the story of Frankenstein is still in the public domain, Universal can’t stop others from making their own Frankenstein movies, books, comics, plays, etc. However, they can and repeatedly have clamped down on those whose reimaginings of the book involved a monster that they felt looked too close to their own.

Since the story of Frankenstein is still in the public domain, Universal can’t stop others from making their own Frankenstein movies, books, comics, plays, etc. However, they can and repeatedly have clamped down on those whose reimaginings of the book involved a monster that they felt looked too close to their own.

This, in turn, has forced other studios to get creative with their version of the monster. For example, when Hammer Films did their Frankenstein films in the 50s, 60s and 70s, they modified the look of the monster so that it would be similar enough to be recognizable but different enough to not be infringing. Various comic book retellings have done the same thing.

However, there’s been a great deal of debate over the years as to what is and is not copyrightable when it comes to Frankenstein’s Monster and, more importantly, which uses are and are not infringing.

According to a recent report from a book publisher, Universal is currently clamping down on any monster that has all of the following elements:

- Green Skin

- Flat Top Head

- Scar on Forehead

- Bolts on the Neck

- Protruding Forehead

According to the report, those are the elements that Universal says define the Universal version of Frankenstein’s Monster. Compre this to the Hammer Frankenstein to the right.

According to the report, those are the elements that Universal says define the Universal version of Frankenstein’s Monster. Compre this to the Hammer Frankenstein to the right.

As you can see, the image lacks a flattop head, has no bolts and only has a slightly protruding forehead. However, it retains its green skin and the scar on its forehead, as well as other visual similarities with the original.

However, this wasn’t the only copyright issue Hammer Films faced in making its Frankenstein movies. For example, with “The Curse of Frankenstein”, the script had to be rewritten multiple times to avoid any similarities to the Universal series, in particular “The Son of Frankenstein”, which was a largely original plot created by Universal.

Still, the movies were made and no lawsuit was filed, however, the shadow of Universal’s Frankenstein’s monster looms large over the entire genre, due to both its iconic status and its current protection by copyright.

Bottom Line

So what does all of this mean in a practical sense? Well, for one, if you, your son or daughter want to dress up as Frankenstein this Halloween, most likely you’ll be doing it in a costume/mask that’s licensed by Universal.

Likewise, other adaptations of the story that use a monster similar to the one in the Universal films need to either get a license or risk facing a lawsuit. This includes, movies, comics, books and other formats.

While you are certainly free to do whatever you want with the source material, the Universal version of Frankenstein’s monster is so iconic and so recognizeable that it would be an uphill battle to create a different version of the monster.

That being said, in 1994, Tristar Pictures did make a more novel-faithful adaptation of the story and it did reasonably well for itself, proving that it’s not impossible.

However, if you want proof how big of an uphill battle this is, ask a child what Frankenstein looks like and you’ll likely see just how deep the connection with the Universal version is, even 80 years after its release.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.