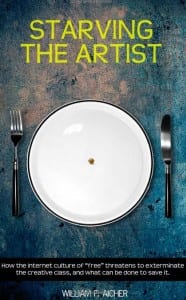

Book Review: Starving the Artist

As copyright becomes more and more of a hot-button issue on the Web, inevitably more and more authors are releasing books on the topic.

The notable books (and controversial) books on the topic released in the past few years have included Digital Barbarians by Mark Helprin, Cult of the Amateur by Andrew Keen, The Little Book of Plagiarism by Judge Richard Posner, Remix by Lawrence Lessig and Free by Chris Anderson (which was the subject of a plagiarism controversy of its own) just to name a few.

However, William Aicher is a relatively new addition to this field. Though he has blogged about copyright-related issues on his site for some time, his first book on the topic, a short self-published work, is a relatively unusual entrant into the field.

But what makes Aicher’s book unique isn’t what can be seen on the cover, but rather that it is a book on copyright that manages to avoid being mired in debates on law, philosophy and/or personal anecdotes. Even more impressive, it avoids personal attacks and even comes across as balanced and nuanced.

Though not particularly earth-shattering, it manages to be friendly enough for a casual reader and still have enough to hold the interest of someone more dedicated to copyright issues.

Still, it seems to be a book struggling for an audience and that may be the biggest flaw the book has.

Background

Aicher’s tome is not a lengthy work by any stretch. At only 70 pages not counting forward and introduction, even an average reader can breeze through this on a lazy afternoon.

The book is divided into three parts.

- Creation: This section discusses the motivations behind creation, monetary and otherwise, as well as the costs of creation and how they are affected by copying.

- Yours and Mine: Here, Aicher writes about the morals and ethics of piracy and other copyright infringement, saving the strongest sting for those who, according to Aicher, build businesses on the back of infringement.

- The Future: Finally, Aicher discusses the current legal and market situation and how it may affect creativity in the near future.

The second section of the book is by far the longest, with the third being just one short chapter long, thus making most of the book closely focused on the ethics of piracy, including both the participatory culture created on the Web and the temptation of free works.

Legally, the book focuses by far most of its energy on the DMCA, specifically the notice-and-takedown regime often discussed here on Plagiarism Today. However, Aicher has taken the view that the system has enabled companies to abuse the law to build businesses on the back of infringement while claiming safe harbor.

All in all though, the book avoids delving too deep into the law, you’ll find no citations of famous cases or legal opinions. Instead, the book draws its rather lengthy references section primarily from news articles and other books, including many listed above. There are even a few Wikipedia entries cited, even though that might not be the best source of information for a book to be treated seriously.

But even with the at-times wonky citations, the book does an overall decent job talking about the issues of creation, copyright and ownership and avoids nearly all of the pitfalls other books fell into.

The Good

What makes Aicher’s book stand out is one word: Balance.

In almost every regard, Aicher’s book manages to straddle the line between two pitfalls without veering of course. For example, though Aicher includes anecdotes in his book, including how he used to run a BBS for sharing guitar tabs in a previous life, the book never feels like an autobiography, unlike Helprin’s book. Though there is a great deal of research and citation, it never feels like a stuffy academic paper, like Lessig’s work can at times. Finally, even though he has sharp feelings on the the issues, he refrains from insults and even admits that everyone is trying to think of the artist’s best interest, unlike both Keen and Helprin in their books.

All in all, the book takes an incredibly even keel. No insults, no excess of academia, no nostalgia. Aicher clearly wants his book to be approachable and read by those who disagree with him and works hard to introduce conflicting opinions and rebut them gently. Though his arguments may not be anything earth-shakingly new, the tone and the way they are presented is very refreshing.

On the whole, Aicher’s book is very well-written and easy to read. It manages to float through the topic of copyright smoothly and comfortably. Much like a ship going through an ocean, it doesn’t merely skim the surface nor does it sink into the depths. Instead floats just deep enough to avoid drowning and takes the reader on a three-hour tour of the copyright issues, without winding up on a deserted island.

The Bad

Though the book is, overall, a solid work. There were a few issues I took with it.

For one, though the book’s brevity is not, in and of itself, a strike against it the book’s third chapter is painfully short. At barely ten pages, the discussion about the future would seem to me to be the most important part of the book, the natural climax of the previous sixty. In fact, one could almost call the previous sixty pages a great introduction for a weightier book about the future of copyright and creativity but, just as the discussion gets truly interesting, the book abruptly ends.

Also, there were also a few minor errors in the book. One example is on page 44 where he refers to the Pirate Party as being anti-copyright and seeking to abolish copyright. However, all Pirate Parties, including Sweden’s, to which he was referring, simply favor extreme copyright reform, in this case reducing the term to five years and making non-commercial file sharing legal.

Another error was on page 61 when Aicher said that the law did not require that DMCA takedowns be filed by either the copyright holder or a designated agent and that such a requirement was the creation of Web hosts. That is simply not true. Section 512(c)(3)(vi) states that a notice must including the following:

A statement that the information in the notification is accurate, and under penalty of perjury, that the complaining party is authorized to act on behalf of the owner of an exclusive right that is allegedly infringed.

In short, if you submit a DMCA notice and you are not either the rightsholder or an authorized agent, you are committing perjury. Red flag takedowns are an unrelated issue that have all but been done away with in recent court decisions.

These errors are relatively minor and at least somewhat understandable given the angle Aicher is taking with the subject, but they serve to misstate the current copyright situation ways that are fairly vital.

Still, the technical details of the book play a fairly minor role in the work and the meat of the book is more about the broader issues. There, the book is solid and, even the parts I disagree with, I’m forced to admit that Aicher makes his case both compellingly and entertainingly.

Bottom Line

I want to recommend this book but I am unsure about who to recommend it to. If you’re reading this site, you probably are familiar with the back and forth of the copyright debate and have heard these arguments before, if not pondered them yourself. If you are interested in the copyfight, you either already agree with him or have your counter-arguments lined up already.

This best audience for this book is, in my view, people who have only a passive interest in the copyright debate. It’s a short, quick read that doesn’t lose even the most lay of the laypeople. It is akin to a tourist visit in the copyright wold, a horse-drawn carriage ride through the pro-copyright side of the argument. It sacrifices depth for breadth and quickness and that makes it approachable and at least somewhat useful to those with but a passing interest.

Unfortunately though, this audience isn’t likely to seek out this book or know to look for it. Even if they were given a copy, I doubt many would read it. Your casual file sharer or person that just doesn’t think about copyright isn’t going to sit down and read a book on the subject, even if they can get through in the time it takes to finish a bottle of wine.

Still, if you are interested in copyright you can do a great deal worse than Aicher’s book. Though far from perfect, short and not ground-breaking, it’s a good book to have on your shelf and considering that a paper copy is only $9.95 and a Kindle copy $4.95, it’s cheap to own and takes almost no time. Just don’t expect to be blown away or have your views changed.

It may not change your life, but it certainly won’t make you regret reading it.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.