Is Flickr Letting Down its Users?

A recent post by photographer J.M. Goldstein raised a very interesting question about Flickr and its API, namely whether or not Flickr was policing its API well enough and doing an adequate job protecting the rights of photographers and artists that post to the service.

A recent post by photographer J.M. Goldstein raised a very interesting question about Flickr and its API, namely whether or not Flickr was policing its API well enough and doing an adequate job protecting the rights of photographers and artists that post to the service.

Goldstein took special issue with a series of recent cases where copyright licenses were being ignored, by users of the Flickr API, the latest of which involved making all Flickr images, regardless of license terms, available for download as cell phone wallpapers on the site Myxer (the article mistakenly reports the images as being for sale, though the download, according to comment 40, was free).

It is very clear that many services and companies that have used the Flickr API have violated copyright holder’s rights, either intentionally or accidentally, and that this is an ongoing issue as new services come online almost every day.

So what can be done to fix this problem? What responsibilities does Flickr have in this? The answers, unfortunately, are neither simple nor easy.

The Power of the API

There is little doubt that Flickr’s API is a very powerful tool. It allows third parties to build services and tools that access Flickr and use the images there in new and exciting ways. It is behind many of my personal favorite tools, including Photodropper.

Also, most applications that use the API do so in a way that is fair to the rights of the artists that use Flickr. It is, fortunately, only a small minority that do not. This is because the API makes it simple to interpret the licensing of the images and Flickr’s terms of service for the API requires developers to respect user intellectual property.

However, some have not and those cases pose a great deal of risk to photographers. Since the infringers are using the API, much like an RSS scraper, they have the ability to take almost everything on the site and do with it as they please. This includes, theoretically, selling the works, creating new, high-resolution galleries and using the works in advertising or promotion.

This has many photographers worried and, judging from the comments on the original article, at least some are abandoning Flickr due to these issues.

Flickr’s Role

Flickr, for their part, is in a bad position here. Their powerful API is one of the critical reasons that both developers and users enjoy the site as much as they do. Flickr’s ability to interact with other services has been critical to its success and removing functionality from the API could be very costly to them.

Flickr, for their part, is in a bad position here. Their powerful API is one of the critical reasons that both developers and users enjoy the site as much as they do. Flickr’s ability to interact with other services has been critical to its success and removing functionality from the API could be very costly to them.

Despite that, Flickr does have both a terms of use that forbids developers from abusing user’s rights and the ability to revoke API keys, thus shutting down services that might be infringing.

However, Flickr has been slow to use this tool against developers, especially those that create products with uses that have legitimate uses. This has not stopped Flickr from shutting down some services trying to access the site, such as it did with the image search engine FeelImage (though FeelImage was not using the API, just a tag search, and has since resumed indexing only CC-licensed material), but such cases usually only take place after a user uproar or if the service is clearly abusive in nature.

The simple truth is that that the vast majority of the responsibility is on users to license their photos correctly and developers to respect those licenses.

Flickr, though it is the middle man, has very little it can do in many cases.

What Flickr Should do

This is not to say that the site is immune from all responsibility or criticism in this matter. There are several things the site can and should do to reduce the number of such incidents.

If I were to make suggestions, I would include the following:

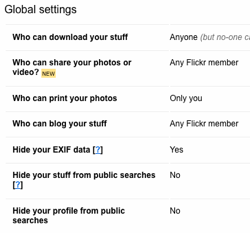

- Clearer User Licensing Terms: The image above and to the right is what I see when I log into Flickr’s privacy options. The options are confusing and overlapping. “Sharing” a photo, for example, allows users to embed or “blog” a photo, which is yet another option, there is also no clear way to remove an image from the API (Note: You have to disable public searching on “3rd Party Sites”) and it is unclear how any of this meshes with Creative Commons Licensing. If this is confusing to me, I can imagine many users feel overwhelmed.

- Quicker Disabling of API Keys: If a developer is infringing on the rights of Flickr users, their API key needs to be disabled, at least until a fix can be made to their system. Though Flickr is understandably uneasy about banning developers for a coding mistake, they could allow such sites 72 hours to correct the problem before disabling them.

- Licensing Trumps API Permissions: Under the current system, the API setting in Flickr trump the licensing settings on the photograph, it either should work the other way around or the user should be given the option to decide which is more important. Otherwise, the copyright licensing is fairly meaningless.

As always, I am seeking other suggestions as to what Flickr can do so please feel free to add your ideas in the comments below. Since I am not a heavy Flickr user, I realize my input is limited.

Conclusions

In the end, the responsibility to respect licenses will always fall on the developers. As with any API, the developer will have the ability to disregard both the terms of use and the rule of law, but have a duty to respect both their own agreements and the user wishes.

While there are steps that Flickr can and should take to reduce this problem, the issue of Flickr-based tools ignoring licensing terms falls squarely on the shoulders of the developers that made them.

If developers do not bear responsibility, legally and ethically, for the works they create, then there is absolutely nothing to stop them from abusing the system even more. They, as well as the users who abuse the tools they create (in some cases), need to be held accountable first and foremost.

Though the frustration with Flickr is understandable and certainly is some grounds for it, they are not the ones who abused the system nor are they the ones who made the mistake.

They just paved the road for those who did.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.