Using Creative Commons to Gain Links, Improve SEO

Many people, myself included, use Creative Commons Licenses to enable and encourage others to share their work. Whether it’s hoping that others will republish blog posts, use their photographs in a site design or remix their music into something new, Creative Commons is a great way for creators to give their work a new life or a new audience.

Many people, myself included, use Creative Commons Licenses to enable and encourage others to share their work. Whether it’s hoping that others will republish blog posts, use their photographs in a site design or remix their music into something new, Creative Commons is a great way for creators to give their work a new life or a new audience.

But with those idealistic reasons come some more practical, real-world benefits. Creative Commons works, when used online, typically come with links. Those links can provide a great benefit both in terms of direct traffic and search engine optimization (SEO) benefit.

In recent years, these tangible benefits have been spending more and more time in the spotlight as companies have tried to exploit Creative Commons Licenses for their own gain. While often this is done within the spirit of the Creative Commons License, some have pushed the boundaries of comfort and even what is allowed/required within the license itself.

All of this begs the question: How useful is Creative Commons for linkbuilding and SEO? Furthermore, what are the boundaries legally and ethically

The PerspecSys Case

My friend and Copyright 2.0 Co Host Patrick O’Keefe recently penned an article about password security aimed at helping community admins and their staff stay safe. Patrick, as part of the article, used PhotoDropper (previous coverage) to find and embed a Creative Commons-Licensed image of a combination lock.

My friend and Copyright 2.0 Co Host Patrick O’Keefe recently penned an article about password security aimed at helping community admins and their staff stay safe. Patrick, as part of the article, used PhotoDropper (previous coverage) to find and embed a Creative Commons-Licensed image of a combination lock.

Since PhotoDropper automatically appends attribution, including a link back to the image source, it met the requirements of Creative Commons attribution.

However, shortly after posting, O’Keefe received an email from a company named PerspecSys, which owns the Flickr account the image was pulled from. According to the email, the attribution was incomplete, saying in part that:

“…we just ask that, per our description on Flickr, that you please provide attribution for the image by making the image, or a note under it, a link to (root domain) rather than to the Flickr page.”

While the request was polite and didn’t threaten any legal action should O’Keefe fail to comply, the request also is not within the bounds of the Creative Commons License.

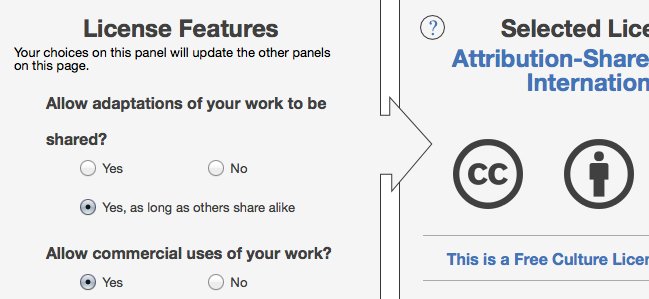

The license that the work is placed under, namely the Creative Commons BY-SA license, requires that, as far as is practical, the person using the image link to whatever page the licensor requests “unless such URI does not refer to the copyright notice or licensing information for the Work.”

Since the home page for the Perspecsys site does not contain any information about the photo (nor even the photo itself) swapping out the link for the domain is technically a violation of the license. Though O’Keefe wouldn’t be in any trouble if he did swap it out, he also wouldn’t be in any trouble if he hadn’t as he was fully complying with the license.

This view is backed up by Mike Linksvayer, a Senior Fellow at Creative Commons, in an email he said, speaking of the issue of attribution links in general, “It goes most off the rails in encouraging people to add a website link to their photo pages on the likes of Flickr, without explaining that the link should be a page with the image and license info for the image.”

This holds true of every version of the Creative Commons License, past and present. None requires that a use of a work link to the home page of the author or anywhere else other than to the original work itself. However, many choose to provide such links both as a courtesy and as a way of saying thank you for allowing the use.

While that is fine, as Creative Commons becomes a popular link-building technique, it’s likely that more and more CC-licensed works will be attached to sites that webmasters will not be comfortable linking to. That has the potential to create a great deal of tension down the road.

Creative Commons as a Link Building Tool

The idea of using Creative Commons a link building tool is nothing new. iAcquire, a marketing and SEO agency, outlined the concept back in 2012, including how to use Google Image Search to track down and reach out to those who use your work but without an “appropriate” link.

The increased attention on Creative Commons isn’t surprising. Recent changes to Google’s algorithms have clamped down on many of the most popular link-building tactics including article marketing, link swapping, link purchasing and so forth. This has impacted both legitimate and spammy sites alike.

It’s easy, in that light, to see the appeal of Creative Commons as a link building tool. Photographs are relatively inexpensive to take or purchase and the sites that use CC-licensed materials are, by in large, legitimate and desirable to get inbound links from.

However, the problem is that the licenses, as they exist right now, don’t directly support this idea. This also means that the automated tools commonly used to find Creative Commons content don’t (and can’t) support it either as they have no way, in most cases, to know where the original site is.

While content creators are free to ask what they want and can make any requests they see fit, the truth of the matter is that, by licensing their work under a Creative Commons License, there is no legal obligation for those using CC-licensed works to comply if they don’t feel comfortable.

And, right now, there a lot of reasons for webmasters to be wary. With linking practices under constant scrutiny by Google, there’s always the threat that even a few bad links could hurt a site’s traffic. After all, no one knows what the next penalty is going to target.

What all of this means is that Creative Commons makes for a poor link building tool. However, the idea can still work, especially if you, like many infographic distributors, provide an embed code for the image that includes a link back to your site. However, that doesn’t necessarily require a Creative Commons License to do.

Regular Creative Commons works, however, are likely not to have external links picked up and, other than kindness, there’s not much to force wary webmasters to provide the links if they don’t want to.

Bottom Line

In O’Keefe’s case, he resolved the issue by simply swapping out the image in question for a different one.

Others will likely do the same, not just because of discomfort with linking practice, but because, for many, it’s the natural reaction when confronted with a copyright issue. This is true even if removal isn’t what is being asked as I’ve seen many times protecting my work, often just asking for attribution, with or without a link.

Personally, I’ve never been aggressive with my enforcement of my CC License. As long as sites have made a good faith effort to attribute the content and aren’t doing anything spammy or unethical, I’ve never cared if the letter of the license was followed.

But as more and more people turn to Creative Commons Licenses as a means to gain links, notoriety and other tangible benefits, the letter of that license is going to draw more and more scrutiny. This is because Creative Commons, for some, is not an ideal but a means to an end.

While there can be debate about whether or not this is within the spirit of the license, it’s clearly a reality that’s here to stay. As such, those who use Creative Commons works need to be aware of it and be prepared for it, including knowing what their rights are if they’re approached.

Note: I reached out to PerspecSys for comment but the have not replied. I will update this article with their response when and if they do.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.