Why Copyright Extensions are Bad for Artists

There has been a lot of talk in recent years about copyright terms and the seemingly never-ending extensions to copyright across the world. Currently, the EU is looking at the possibility of nearly doubling its copyright term on music recordings and the U.S. tacked on another 20 years to its copyright law just a decade ago.

Those who make a living from copyrighted works seem to support these extensions with an almost blind fervor. Though the current copyright term in the U.S. is the life of the author plus seventy years for works of personal authorship and 95 years for works of corporate authorship, many see “more” as universally being “better”.

The problem is that these copyright extensions come with a series of new problems and authors, musicians and others who support them may be unwittingly shooting themselves in the foot. The longer a work is protected, the more concessions they have to give up to make copyright viable.

In the end, most artists would do much better with a limited term of strict control than a century of dubious one. Sadly, we’re already seeing the signs of this problem and there may be no turning back.

A Brief History

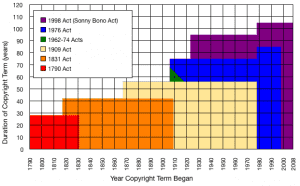

As this chart on Wikipedia illustrates, the copyright term in the U.S. has only moved one direction, up (Note: The Chart is by Tom Bell and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 3.0 License).

To shorten a very lengthy story, the first copyright law in the U.S. was passed in 1790 and set the copyright term to 14 years with the option to renew for another 14. A follow up in 1831 extended the term to 28 years with the option to renew for another 14. Then in 1909 it was extended to 28 years with the possibility of another 28 year renewal.

Then, in 1976, the law was completely rewritten to provide authors with a term for their entire life plus 50 years and corporations a 75 year term. Both of those terms were extended by 20 years in 1998 with the most recent copyright extension.

In short, over the course of just over two centuries, we extended copyright from a max of 28 years to a term that could, depending on how long an author lives, last well over a century and a half. While this might seem to be a big win for copyright holders, who can now will their copyright interests to their great-grandchildren, it creates a series of problems that artists need to consider.

Give and Take

The problem for artists is that copyright law is about balancing the rights of the artist over their work with the needs of the public. The artist has a right to commercially exploit their work, the public has the right to free speech and to create works of their own.

If the balance between those two things is disrupted, the entire system grinds to a halt. It is a delicate, fluid balance that has shifted with technology and culture for over 200 years.

But what this means is that, if you give artists a boon, such as a huge extension to their copyright term, inevitably, they are going to lose rights somewhere else. If copyright holders want a copyright term that lasts for 150 years, they will only receive rights that are sustainable for that long.

It may seem to be impossible, especially since the process is so slow moving, but the legal backlash has already started and may hit home sooner than many think.

The Orphan Works Problem

The classic example of this push back is the Orphan Works legislation.

One of the problems with a copyright term longer than a century in many cases is that the copyright in the work actually outlasts the material it is created on. Photographs fade, hard drives deteriorate, paper rots, etc.

This means that it is impossible for those that wish to archive a work to do so before it is gone forever. Since, in many cases, the author can not be located and permission can not be granted, our lengthy copyright term virtually guarantees the destruction of countless works, many of which may be valuable to our culture and our history.

However, Congress, quite correctly, realized that the public has a legitimate need and is served well by having its history and culture preserved so, in response to that, it has made two runs as orphan works legislation (the last one dying last year before the election) and will likely make a third soon. These bills would have made it legal to use copyright-protected works, under certain guidelines, if the copyright holder can not be found.

This, in turn, puts a huge dent in the rights of an author, at least in terms of practical enforcement and, instead of having full rights over their work for a period of time, copyright holders now have to worry that their works could become orphans the second they place them on the Web or in any public place.

The orphan works problem is not going away and it will come up again soon. However, this won’t be the only issue of its kind. As copyright lobbies push the term toward “forever minus one day” they’re creating more problems with the balance in copyright and these problems will have to be resolved somehow.

Foreseeable Consequences

What are some other potential consequences of a never-ending copyright term, consider some of the following possibilities:

- Legalized “Abandonware”: Abandonware is a term used to describe software that is no longer commercially available, like old games. Currently it is illegal to make copies of abandoned creations, software, artistic or otherwise, but with current copyright laws, a work that is not legally available disappears for many decades. It is foreseeable that there might be a legal shift to legalize some instances of copying unavailable works, possibly even including books, music, etc. On that front, Google Book Search may be a non-legislative start to the process.

- Compulsory Licenses: We already see compulsory licenses for a lot with nondramatic musical works but it is very foreseeable that we could see a future where these licenses are expanded to include other kinds of work including visual, written, etc. Though this might be preferable to the orphan works legislation, it would still create problems for artists wanting to control their name and image.

- Broader Fair Use Provisions: It is also wold make sense to broaden the fair use provisions of copyright law to counter the growing copyright term. We already have one of the broadest fair use systems in the world, but it has served as the main balancing force between copyright ownership and public interest. It would be a natural choice to expand even further as the term expands, possibly to include new variables such as availability of the work, age of the work (not just whether it is published) and so forth. Much of this is already weighed in some capacity, but it could be codified into the law and fair use exemptions could be greatly broadened.

The problem with all of this is that it requires new legislation and the one thing I’ve learned in years of watching copyright legislation is that new laws almost always equal bad laws. New laws mean unintended consequence, legal uncertainties and new problems.

However, the balance has to be preserved and we have to assume that if it takes new laws to achieve it, then new laws we will see.

Bottom Line

A simple, clear cut and shorter copyright term would probably suit more artists than a longer, ambiguous and limited one. The only copyright holders that benefit from such a system are artists with the resources to navigate the potential minefield and works that will continue to generate revenue decades down the road.

The copyright system is and always has been about a balance between creators and the public, if that balance becomes askew, once can rest assured that new laws will be passed to correct. Blindly trying to expand copyright law, especially through term extensions, there will be concessions elsewhere.

It’s time for artists to stop thinking that more is always better and decide what balance would work best for them while still maintaining the spirit of what copyright law is supposed to achieve.

If we can do that, we might finally bring some sanity to copyright on the Web and everyone would be a little bit happier.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.